Diagnosing Traumatic Brain Injuries

Biomarker Called Neurofilament Light Chain (NfL) May Hold the Most Promise

CREDIT: PASHTUN SHAHIM, NIH CLINICAL CENTER

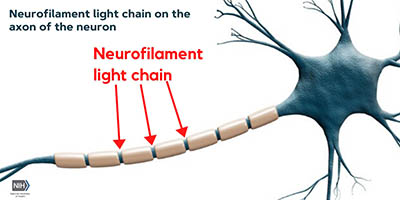

NIH researchers reported that a blood biomarker called neurofilament light chain (NfL) may hold the most promise for predicting, diagnosing, and following up on traumatic brain injuries. Shown: The location of neurofilament light chain on the non-myelinated section of the neuron’s axon. [This was the focus of the Neurology article: Neurofilament Light as a Biomarker in Traumatic Brain Injury]

It’s always been tricky to diagnose mild traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) because there are no reliable blood, neuroimaging, or other tests. In three papers that were recently published in Neurology, NIH researchers reported that a blood biomarker called neurofilament light chain (NfL) may hold the most promise for predicting, diagnosing, and following up on TBIs. When compared with three other blood biomarkers and with neuroimaging, NfL was better at identifying patients who had mild, moderate, or even severe brain injury.

After injury to brain tissue, indicators of cellular damage are released into the blood and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF). NfL is one such indicator.

Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are some of the current testing mechanisms, but each imaging method has its limitations. Imaging is expensive and imprecise.

“For mild events without much trauma, imaging is less useful,” said Leighton Chan, chief of the Rehabilitation Medicine Department at the NIH Clinical Center, and senior author on two of the papers. “Scans show images of anatomic abnormalities, without providing much insight into brain function.”

In one study—“Neurofilament Light as a Biomarker in Traumatic Brain Injury”—the researchers found that in a group of Swedish hockey players, “that serum NfL concentrations highly correlated with CSF NfL levels, showing that serum NfL reflects CSF NfL,” said Pashtun Shahim, a staff scientist in the Rehabilitation Medicine Department and first author on the two papers. (Neurology Jul 2020, DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009983)

Leighton Chan

Pashtun Shahim

That’s good news for people who would prefer a simple blood test over the lumbar puncture needed to obtain the CSF.

The researchers also observed that NfL concentrations were associated with more concussions and greater severity of post-concussion symptoms after a year. NfL predicts how long professional hockey players would be symptomatic from acute concussions and distinguishes which players could return to play from those who could not. Ultimately, the study showed that, compared with concentrations in control subjects, blood NfL concentrations in hockey players with TBIs presented strong diagnostic capabilities in identifying mild, moderate, and severe TBIs.

In the second article—“Time Course and Diagnostic Utility of NfL, tau, GFAp, and UCH-L1 in Subacute and Chronic TBI”—the scientists studied four proteins, including NfL, that collect in the brain after a TBI from patients at the NIH Clinical Center. The results showed that blood NfL was better than the other proteins at distinguishing patients with mild, moderate, and severe TBI from each other; NfL remained elevated five years post-TBI. (Neurology Jul 2020; DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009985)

“While no biomarker reliably detects subtle brain injury over time, the study shows serum NfL elevates after injury and remains high five years after a TBI event, suggesting ongoing axonal degeneration years after the initial event,” said Shahim.

The study also showed that blood NfL had the strongest association with results from advanced brain imaging than did the other proteins.

Jessica Gill

In another Neurology paper—“Exosomal Neurofilament Light: A Prognostic Biomarker for Remote Symptoms After Mild Traumatic Brain Injury?”—that came out a month before the other two, Senior Investigator and Acting Scientific Director Jessica Gill (National Institute of Nursing Research) compared NfL concentrations in military veterans who had no history of TBI with those who had one or more TBIs. She led a team of researchers (including Shahim) that found a significant correlation between higher NfL concentrations in veterans with a history of repetitive TBIs, with length of time in years since the last TBI, and with increased severity of neurological and behavioral symptoms. The results indicate that NfL has superior diagnostic and prognostic performance for mild, moderate, and severe TBI. (Neurology 94:e2412–e2423, 2020; DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009577)

In addition, blood serum NfL captures subtleties in brain function that may not be reflected in CT scans and MRIs and predicts long-term outcomes. NfL has important applications in hospitals and for fields ranging from sports to the military.

“By developing a better understanding of the neuronal underpinnings that contribute to chronic symptoms following a brain injury, clinicians can intervene proactively and anticipate symptom onset if NfL peaks at a certain level or a certain time point following the injury,” said Gill.

The findings from all three studies suggest that—compared to advanced brain imaging or with other blood biomarkers, measuring NfL concentrations in the blood may offer an easier, faster, and more cost-effective way to diagnose TBI and predict outcomes even years after the event occurred.

Frances Fernando is a postbaccalaureate fellow in the Division of Intramural Population Health Research (Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development) and has been at NIH since 2019. After completing her NIH training in 2021, she plans to pursue a doctorate in public health to work on integrative global health issues and human rights. Outside of work, she gardens and explores Washington D.C. by bike.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, March 22, 2022