The SIG Beat: COVID-19

NEWS FROM AND ABOUT THE SCIENTIFIC INTEREST GROUPS

COVID-19 SIG Lecture: NCI’s David Kleiner and Stefania Pittaluga Discuss What Autopsies Have Taught Us About COVID-19

Autopsies can offer a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of COVID-19, the disease caused by the severe acute respiratory-syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). But few autopsies have been performed partly because of logistical issues such as shortages of appropriate personal protective equipment, reluctance of medical staff to conduct autopsies on these patients, difficulty in obtaining consent from the families of the deceased, and lack of transportation for the bodies. In addition, patients are frequently hypoxic at the time of death and have underlying conditions that interfere with the quality of tissue obtained during autopsy.

Two NIH researchers, however, have collaborated with colleagues who performed autopsies on COVID-19 patients at New York University’s Winthrop Hospital (Mineola, New York). David Kleiner and Stefania Pittaluga, senior research physicians in the National Cancer Institute’s Laboratory of Pathology, reported their findings at a July 22, 2020, virtual lecture sponsored by the COVID-19 Scientific Interest Group.

David Kleiner

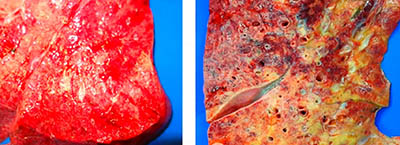

Kleiner highlighted histopathological findings in 18 autopsies of which 16 were sent to NCI for a second review. The most common finding, diffuse alveolar damage (DAD), was present in 15 of the 18 patients. DAD is a change in the lung structure that results in damage to the alveoli and is most often associated with acute respiratory-distress syndrome. When DAD reaches the fibrotic stage, the oxygenation of blood and tissue is severely impaired. Lungs with end-stage DAD are pale yellowish due to the fibrosis, and the lungs take on a honeycomb appearance in which open-air spaces are lined by fibrotic tissue. Once fibrosis occurs, the lungs cannot recover.

In addition to DAD, some patients experienced severe pneumonia before they died. These superinfections occur in some COVID-19 patients even though antibiotics were administered. In several patients, Kleiner noted a striking finding of bacterial overgrowth in the lungs and in multiple extrapulmonary sites 24 hours after death, equivalent to what would be expected in a body that had been unrefrigerated for a week. The full effects of SARS-CoV-2 on the immune system remain unclear.

CREDIT: AMY RAPKIEWICZ (NYU-WINTHROP)

Diffuse alveolar damage (DAD) in the lungs was a common finding in the COVID-19 autopsies conducted by the NCI researchers and their NYU colleagues. Shown: early-stage DAD lung (left); late-stage DAD lung (right).

“Antibiotics help, but without an intact immune system, they don’t do everything, so something must be going awry,” said Kleiner. “If we understand that, [we can] help patients survive this better.”

Kleiner also presented a variety of autopsy findings in other organs as well as in the lungs. Microthrombi, microscopic clots, composed of largely platelets in both the lungs and other tissues were common, as was sinusoidal dilation, or enlargement of the liver sinusoids. Sinusoidal dilation is caused by congestion in the liver parenchyma as a result of backup in the vasculature from pulmonary issues. Other organs that experienced damage were the kidney, heart, and neuromuscular systems.

Stefania Pittaluga

Pittaluga’s talk focused on localization of the virus and cytokine and chemokine expression. In situ hybridization, a sensitive technique allowing for the detection of specific nucleic acid sequences, was used to identify SARS-CoV-2 in tissues. SARS-CoV-2 was detected in five of the 16 cases sent to NCI for review, but greater viral loads were found in patients who had died early in the disease. Two of the patients died in the emergency room and had had symptoms for only a short period of three to seven days. Autopsy findings from these patients are helpful in separating what the virus itself is doing from the cascade of events resulting from the activity of the immune system in patients who died later in the disease course. Unfortunately, many COVID-19 patients die at home or have died before they reach the hospital, making autopsies of patients who died early in the disease almost impossible.

One patient who died early in the disease had strikingly high interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression with IL-6 present throughout the lungs and in the endothelial cells and macrophages of several organs. Although the sample size for this observation was small, further investigations into the role of IL-6 in disease progression will help determine whether anti-IL-6 drugs such as tocilizumab are an appropriate course of treatment.

“Autopsies are still important,” Pittaluga concluded. Despite the challenges that come from conducting autopsies on COVID-19 patients, the information gained plays an essential role in understanding the pathophysiology of COVID-19.

To view a videocast of this lecture, “COVID-19 Autopsy Findings: A Joint Effort Between NYU Winthrop Hospital and NCI–What Have We Learned So Far,” presented on July 22, go to https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=38104. For more information about the COVID-19 SIG as well as links to resources and to other COVID-19 lectures, go to https://oir.nih.gov/sigs/covid-19-scientific-interest-group. The COVID-19 SIG lecture series will resume in mid-October, and the SIG will also be hosting a symposium on October 29 and 30, 2020.

Emma Rowley is in her second year as a postbaccalaureate fellow in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease’s Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research where she is investigating the impact of oxidative stress on Plasmodium vivax, a parasite that causes malaria. In her spare time, she enjoys baking and reading books about infectious diseases.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, March 22, 2022