From the Annals of NIH History

Dr. Joseph Goldberger and Pellagra: A Fearsome Disease Tamed

CREDIT: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Joseph Goldberger (1874-1929) identified a nutritional deficiency as the cause of pellagra in the early 1900s. It wasn’t until 1937, however, that niacin, also called vitamin B3, was proven to be the specific missing component that caused the disease.

To live in the American South in the early 1900s, you would have had to survive an uncontrolled epidemic known for its fatal consequences. The disease, pellagra, had been a worldwide scourge for about two centuries, with no known treatment. In 1909, pellagra was reported in 26 states and caused the deaths of at least 10 people per day. In 1912, South Carolina reported 30,000 cases with a mortality rate of 40%, making pellagra the second most common cause of death in that state. No one knew what caused pellagra, but the consensus was that it was an infectious disease carried by an unknown organism, possibly in spoiled corn or cornmeal.

Pellagra was known as the illness of “four Ds”: diarrhea, dermatitis, dementia, and death. Other signs included sensitivity to sunlight, hair loss, swelling, beefy red tongue, trouble sleeping, weakness, dilated cardiomyopathy (enlarged, weakened heart), nerve damage, and difficulty with balance.

Congress demanded action and asked the surgeon general to investigate the disease. So, in 1914, Joseph Goldberger, an epidemiologist employed by the Hygienic Laboratory (forerunner of NIH), was assigned the task of determining the etiology of pellagra and hopefully finding a cure.

Goldberger learned that institutions such as orphanages and prisons had the highest number of pellagra cases, so he started his investigation there. He quickly challenged the infectious organism theory, noting that none of the caregivers or physicians in contact with children or guards in the prisons ever got ill with pellagra themselves. Also, pellagra was not present in orphans under the age of six or in those over the age of 12. Only those aged seven to 11 were sick.

Why was pellagra contained within a specific age group? Goldberger evaluated this strange presentation and asked whether these groups were treated differently. They were—their diets were different. In addition to the basic diet of biscuits, cornmeal mash, grits, molasses, sowbelly, and gravy, the one- through six-year-old orphans had milk, those over 12 were given meat, but the seven- to 11-year-olds weren’t fed milk or meat.

With the spread of bacteriology, the theory of infectious disease was becoming accepted by physicians at this time, which perhaps explains why other physicians blamed an infectious organism. But Goldberger thought that perhaps the absence of certain nutrients was responsible for pellagra. He asked that a glass of milk be given daily to the children age seven to 11 to supplement their diets. The result: the rapid cure of existing skin lesions and a major decline in the incidence of this dreaded disease. Goldberger had determined that pellagra was caused by a deficiency of unknown nutrients, rather than by infectious organisms.

This observation was repeated in a prison where the number of cases of pellagra was high and confirmed by multiple well-designed experiments with healthy individuals, including Goldberger, who could not be “infected” from blood or excreta from ill patients. The prison diet included cornmeal, but no protein and few vegetables.

CREDIT: NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Institutions such as orphanages and prisons had the highest number of pellagra cases because of the poor nutritional value of the food. Shown: a child with dermatitis, one of the symptoms of pellagra.

The medical establishment and, particularly, Southern political leaders rejected Goldberger’s identification of nutritional deficiency as the cause of pellagra. He spent the last 15 years of his life trying to isolate the unknown nutrient but never accomplished his goal.

It was not until 1937 that niacin, also called vitamin B3, was proven to be the specific missing component that caused pellagra. Niacin is normally present in meat, meat products, and green vegetables, but not in untreated corn.

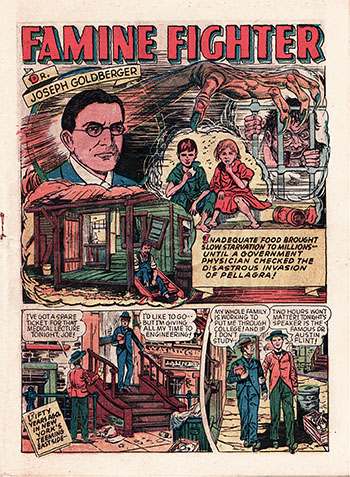

Because of Goldberger’s persistence, pellagra nearly disappeared, and most Americans don’t even realize that a totally preventable nutritional deficiency once caused thousands of deaths. In 1943, however, Real Life Comics made Goldberger a subject in its “Real Life Heroes” issue. You can see part of the comic strip and learn more about Goldberger at a display near the third-floor elevators in Building One.

CREDIT: BERT HANSEN COLLECTION, HARVEY CUSHING/JOHN HAY WHITNEY MEDICAL LIBRARY, YALE UNIVERSITY

In 1943 Real Life Comics made Goldberger a subject in its “Real Life Heroes” issue, for his efforts to fight pellagra.

To read more about Joseph Goldberger, go to https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/Goldberger/index.html.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, March 30, 2022