Featured Fellow

Andrea Burke: Rare Ambition

Finding Treatments for Rare Bone Diseases

The young teenage girl “just wanted to get better and look normal,” recalled NIH dental clinical research fellow Andrea Burke. The girl’s face was asymmetrical, with one eye higher than the other, and the underlying bones were deformed. “It was difficult for her to be around her peers.”

She was suffering from a rare bone disorder called fibrous dysplasia (FD) in which abnormal fibrous tissue develops in place of normal bone. Burke was an oral and maxillofacial surgery resident at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston when she saw the girl for the first time in 2012. The patient, who’d been diagnosed with FD at age six, had already had four surgeries to recontour the craniofacial bones, fix the eye socket, remove excess tissue, and even extract teeth so she could smile and eat properly. But the bony tissue kept growing back.

“The family was desperate,” said Burke. How many more surgeries would it take to put a stop to the uncontrollable bone growth?

What little is known about the biology of FD, including that it’s caused by mutations in the GNAS gene, is based on work done at the NIH. FD is usually detected when a patient is young. As the bones develop abnormally, skeletal aberrations become obvious—facial bones may become asymmetric, the spine may curve, and one arm or leg may appear longer than the other. Fibrous dysplastic bones may be painful, and, because they are weaker than normal bones, more likely to break. In FD, normal bone has been replaced by fibrous tissue and varying degrees of abnormal under-mineralized, or bonelike, matrix.

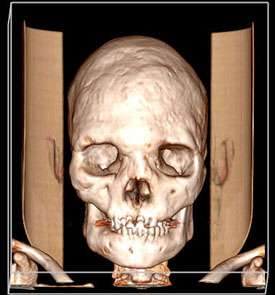

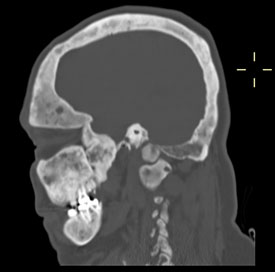

CREDIT: ALISON BOYCE, NIDCR

(Top) A skull showing evidence of fibrous dysplasia; (bottom) X-ray of the same skull.

Treatment options are limited to using medications to manage pain, performing surgery to repair or strengthen weak or broken bones, or shaving away excess bone. But in many instances, the fibrous tissue grows back.

It made no sense to Burke that doctors kept removing the fibrous tissue instead of finding a way to stop it from returning. Didn’t they want to understand the cellular and molecular underpinnings explaining why the tissue continued to regrow? Burke did. And so began her journey into research on rare bone diseases.

No choice but to operate

Although Burke and her mentor, Leonard Kaban (at Mass General), had no choice but to operate on the teenager to recontour her facial bones yet again, they decided to have some of the removed tissue analyzed by an expert in bone biology and mineral metabolism: NIH endocrinologist Michael Collins, chief of the Skeletal Clinical Studies Section at the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). His research at the NIH Clinical Center with patients from all over the world has helped to define evidence-based therapies for rare bone diseases.

It turned out that the girl’s fibrous tissue had an overexpression of receptor activator of nuclear factor–kappa-B ligand (RANK-ligand), a factor that’s in part responsible for increased osteoclastic bone resorption and bone loss in postmenopausal women. Collins had found that a drug called denosumab, used to treat postmenopausal bone loss in women and metastatic bone tumors, stopped the growth of fibrous tissue in two of his patients with aggressive FD. So, with the family’s permission, Burke and Kaban started the girl on the drug. It worked. In combination with surgery, the treatment helped her to look more normal and “gave her confidence,” Burke said.

After completing her residency in 2013, Burke was determined to conduct research on FD and other rare bone diseases. She didn’t want to go directly to a job at a dental school or clinic where she might not have protected time for research. So she came to work as a dental clinical research fellow in the NIDCR with Michael Collins and senior investigator Pam Robey.

“Here at the NIH, you can find the world’s expert in a rare disease just down the hall,” said Burke. “Or, if you are fortunate like me, you can work in a lab dedicated to the rare disease.”

PHOTO BY ERNIE BRANSON

Dental clinical research fellow Andrea Burke (left) works with clinical research nurse Padmasree Veeraraghavan at the NIH Dental Clinic. When Burke is not in the lab or clinic on the NIH campus, you might find her jamming to jazz at a festival in New Orleans, hiking the glaciers in Patagonia, skiing in New Zealand, or scuba diving in Fiji.

Burke does see patients at the NIH Clinical Center, but she also has plenty of time for research. In the operating room, she removes bony growths from skulls of patients with FD, who donate the tissue specimens for research. She uses whole-exome sequencing and other molecular methods to analyze and describe genetic variants in the tissue. She would like to one day develop a biobank of samples for future research.

“We believe that many of these rare craniofacial bone diseases exist along the same pathophysiologic spectrum [but] with different mutations,” said Burke. “We want to better characterize them.”

Characterizing tissue from rare bone diseases may make it possible for surgeons to better predict treatment responses and thus spare certain patients from having aggressive surgeries. Burke envisions a future in which treatments for rare bone diseases are individualized and—along with clinical, radiographic, and histopathologic assessments—based on precise, molecular evaluations of a patient’s unique biology. She hopes that one day she can offer patients an alternative to surgery.

“Our group here tries to avoid surgery until patients reach skeletal maturity and/or the lesions stop growing,” said Burke. If surgery is done when the patients are too young, “the bone can keep growing back and sometimes you end up chasing your tail. The ultimate goal is to know when surgery is best.”

Early interest in dentistry

Burke’s interest in dentistry had its roots in college when she volunteered at a dental clinic that had two female dentists. She also shadowed her family dentist. Even then, she began to wonder why so little was known about common dental problems such as tooth pain and sensitivity to hot and cold temperatures. Later, after graduating from Barnard College (New York) with a degree in biology, she worked in a research lab at Columbia University College of Dental Medicine (New York). Her first experience at NIH was in 2004, between her first and second years at Harvard School of Dental Medicine (Boston), when she was selected as an NIH Summer Research Student in NIDCR’s Functional Genomics Section. There she used microarrays from patients with tooth diseases to identify altered gene-expression profiles in the dentin-forming cells.

As her research experience grew, Burke was puzzled that so many fundamental biological questions go unanswered. Her strong need to answer those questions is what inspires her to pursue research. The answers she most wants to find are those that will lead to improvement in clinical care and patients’ quality of life.

Burke and collaborator Alison Boyce, a pediatric endocrinologist in NIDCR’s Skeletal Clinical Studies Section, along with members of the Fibrous Dysplasia Foundation, are developing a patient registry to collect information that can be aggregated and analyzed. A patient registry, paired with the results of Burke’s basic research, will help her reach her goal of providing clinicians with tools for evidence-based treatment planning.

“We’re thrilled that Dr. Burke is choosing to focus her career on fibrous dysplasia,” said Deanna Portero, the executive director of the Fibrous Dysplasia Foundation. “Brilliant and motivated researchers like her are desperately needed.”

Burke is completing her NIDCR fellowship this fall and will be moving on to an academic position at a medical research center (the exact location had not been confirmed before the NIH Catalyst went to press). There she will continue her research as well as see patients and teach classes in oral and maxillofacial surgery. She also hopes to stay active with the Collins group and the foundation.

But what gives her the most satisfaction is knowing that she can help people like the young girl she first met at Massachusetts General three years ago. That teenager is now a regular visitor to the NIH Clinical Center and taking part in a natural history clinical trial on FD. Burke is pleased that the girl’s condition seems to be under control and that she’s gained a lot more confidence in herself.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 13, 2022