The Training Page: Plain Language Posters

Scientific Posters in Plain Language

The Lay Audience Includes Potential Collaborators and Funders

When you think of a scientific poster, you may picture minutely detailed text of dense information colored only by a bar graph or a grossly enlarged microscopic image. But at a symposium held at NIH in December 2013, researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) experimented with a new approach: translating their posters into language accessible to the lay public. Of the more than 100 posters presented during the symposium, 11 were of the plain-language variety.

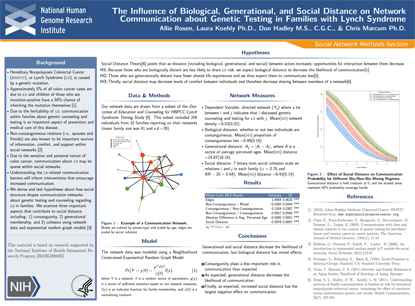

One of the plain-language posters, presented by NHGRI staff scientist Christopher Marcum, depicted an analysis of families and social networks of people with Lynch syndrome, an inherited genetic condition that greatly raises the risk of colorectal cancer and many other cancers. With the help of summer intern Allie Rosen (an undergraduate student at Brown University in Providence, R.I.), Marcum rewrote the abstract that had appeared on Rosen’s traditional scientific poster—“The Influence of Biological, Generational, and Social Distance on Network Communication about Genetic Testing in Families with Lynch Syndrome.” He renamed the poster “Communication is Key! Understanding How Families at Risk for Cancer Talk About Genetic Testing and Counseling through Social Networks” and replaced the complex graphs and long formulas with simpler, easy-to-understand images.

The process of translating complex information for a nonscientific audience was not easy…but it was worthwhile. “We have to be able to communicate scientific ideas not just to Congress and policymakers, but also to the average person,” he said. “I want to start integrating plain language into the discussion of scientific papers.”

The 2013 symposium was the first time that NHGRI included posters that swapped the complex and technical language of traditional scientific posters for images, graphics, and simple language geared to the average person.

“In their research, [scientists] are looking at a lot of specific and very important details,” said NHGRI Scientific Director Dan Kastner, whose office organized the symposium. “As they advance in their careers, they will need to be able to explain the science to regular people.”

To get started on her plain-language poster, NHGRI postdoctoral fellow Melissa Harris read magazines such as Scientific American to see how its writers present information to intelligent, non-scientist audiences. She figured out how to use terminology she knew her mother would understand and defined all technical terms.

Melissa Harris, a postdoctoral fellow in NHGRI’s Mouse Embryology Section, Genetic Disease Research Branch, enjoyed being creative as she crafted her plain-language poster on gray hair and aging.

Entitled “Aging and Stem Cells: What Our Gray Hairs Are Telling Us,” her poster explained in lay terms how understanding the process of hair graying in mice provides a window into biological changes that cause aging. In particular, she focused on melanocyte stem cells, which contribute to pigment production in hair follicles and disappear with age.

The experience “gave me the freedom to use my artistic side and to use language in a different way,” said Harris. Still, she didn’t want to make the science “so superficial that people don’t take it seriously.” As it turned out, the plain-language poster triggered many more in-depth conversations with attendees than did traditional posters. It was such a good experience that she expects to integrate plain language into her scientific posters from now on.

Marin Allen, NIH’s deputy associate director for Communications and Public Liaison, who oversees NIH’s plain-language initiative, applauded the scientists for presenting plain-language posters.

“They focused on the technical skills required for the effective use of plain language and captured the spirit of clear communication,” she said. “I hope this model will be adopted by many others.”

Here are Marcum’s and Harris’s tips for developing plain-language scientific posters:

- Explain your research in the way you’d explain it to your parents or a friend who is not a scientist. Doing so will help you write an abstract that average people can understand.

- Don’t assume that you’re being too basic or that the science behind your research is common knowledge.

- Make sure to prepare in advance. Creating the poster may take longer than expected—as much as two to three days.

- Don’t think that using plain language means you’re undermining the significance of your work. The researchers received more interest in their plain-language posters than in their traditional ones.

To learn more about the plain-language initiative, which encourages NIH communications offices to use clear, concise language in all documents written for the public, other government entities, and fellow workers, go to http://www.nih.gov/clearcommunication.

BEFORE AND AFTER

Christopher Marcum, a methodologist in NHGRI’s Social Network Methods Section in the Social and Behavioral Research Branch, based his plain-language poster on a traditional scientific poster that depicted the same research. Note the differences between them.

THE TRADITIONAL SCIENTIFIC POSTER

“The Influence of Biological, Generational, and Social Distance on Network Communication about Genetic Testing in Families with Lynch Syndrome”

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), or Lynch syndrome (LS), is caused by a genetic mutation.

- Approximately 5% of all colon cancer cases are due to LS, and children of those who are mutation-positive have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation themselves.

- Due to the heritability of LS, communication within families about genetic counseling and testing is an important aspect of prevention and medical care of this disease.

- Non-consanguineous relations (i.e.that is, spouses and friends) are also known to be important sources of information, comfort, and support within social networks.

- Due to the sensitive and personal nature of colon cancer, communication about LS may be sparse within social networks.

- Understanding the LS-related communication barriers will inform interventions that encourage increased communication.

- We derive and test hypotheses about how social structure shapes communication networks about genetic testing and counseling regarding LS in families. We examine three important aspects that contribute to social distance including: 1) consanguinity, 2) generational membership, and 3) cohesion using network data and exponential random graph models.

PLAIN LANGUAGE VERSION

“Communication Is Key! Understanding How Families at Risk for Cancer Talk about Genetic Testing and Counseling through Social Networks.”

People with Lynch syndrome (or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) have higher rates of certain cancers, which are caused by a genetic mutation. Approximately 5% of all colon cancer cases are due to this syndrome, and children of parents who carry the mutation have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation themselves. It is important that those at risk of inheriting the mutation discuss genetic counseling and testing with the members of their social network, especially biologically related family members. Although only biologically related family members share the increased risk for Lynch syndrome, social relations (such as spouses, step-parents, and friends) are known to be important sources of information, comfort, and support within social networks. Due to the sensitive and personal nature of the topic of colon cancer, there may not be a lot of communication about Lynch syndrome within social networks. Understanding who talks to whom can inform interventions that encourage increased communication about HNPCC risk and genetic testing within these networks.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 27, 2022