Research Briefs

NIA: NEW GENE MUTATION ASSOCIATED WITH ALS AND DEMENTIA

An NIA-led team of scientists has found a rare gene mutation associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The gene is involved in RNA metabolism, which is part of the control mechanism determining protein synthesis within the cell.

ALS, often referred to as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a rapidly progressive, fatal neurological disorder that kills about 6,000 Americans each year. The disease attacks and kills nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord; people with ALS lose strength; the ability to move their arms, legs, and body; and eventually, the ability to breathe without support. About 10 percent of people with ALS have a directly inherited form of the disease.

Working with DNA samples from families in which several people had been diagnosed with ALS and dementia, the investigators used exome sequencing—a technique in which the entire coding regions of DNA are sequenced—to identify the mutation in the MATR3 gene, which is located on chromosome 5 and encodes the protein matrin 3. Further investigation revealed an interaction between matrin 3 and transactive-response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa, an RNA-binding protein whose mutation is known to cause ALS.

The identification of this mutation in MATR3 gives researchers another target to explore in the pathogenesis of ALS. In addition, it provides additional evidence that some disruption in RNA metabolism, an essential process within all cells, is involved in neuron death in ALS. (NIA authors: J.O. Johnson, R. Chia, A.E. Renton, H.A. Pilner, Y. Abramzon, G. Marangi, J.R. Gibbs, M.A. Nalls, A.B. Singleton, M.R. Cookson, B.J. Traynor, Nat Neurosci DOI:10.1038/nn.3688)'

NIEHS: OBESITY PRIMES THE COLON FOR CANCER

Obesity, rather than diet, causes changes in the colon that may lead to colorectal cancer, according to an NIEHS study using mice. The finding bolsters the recommendation that calorie control and frequent exercise are not only key to a healthy lifestyle, but also a strategy to lower the risk for colon cancer, the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States.

A large body of scientific literature says people who are obese are predisposed to a number of cancers, particularly colorectal cancer. To better understand the processes behind this link, the researchers fed two groups of mice a diet in which 60 percent of the calories came from lard. The first group of mice contained a human version of the gene NAG-1, which has been shown to protect against colon cancer in other rodent studies. The second group lacked the NAG-1 gene.

The NAG-1 mice did not gain weight after eating the high-fat diet, while mice that lacked NAG-1 grew plump.

The researchers also noticed that the obese mice exhibited molecular signals in their gut that led to the progression of cancer, but the NAG-1 mice didn’t have those same indicators. Specifically, the researchers isolated cells from the colons of the mice and analyzed for epigenetic changes by examining the acetylation changes in the cells’ histones.

It turned out that the acetylation patterns for the obese mice and the thin NAG-1 mice were drastically different. Patterns from the obese mice resembled those from mice with colorectal cancer. The additional weight they carried also seemed to activate more genes that are associated with colorectal-cancer progression, suggesting the obese mice are predisposed to colon cancer.

The researchers want to determine exactly how obesity prompts the body to develop colorectal cancer in hopes of one day being able to design ways to treat or prevent colorectal cancer in obese patients. (NIEHS authors: R. Li, S.A. Grimm, K. Chrysovergis, J. Kosak, X. Wang, Y. Du, A. Burkholder, T.E. Eling, P.A. Wade, Cell Metab 19:702–711, 2014)

NHLBI: RESEARCHERS FIND REASON WHY MANY VEIN GRAFTS FAIL

NHLBI researchers, with the help of other scientists, have identified a biological pathway that contributes to the high rate of vein-graft failure after bypass surgery. Using mouse models of bypass surgery, they showed that excess signaling via the transforming growth factor–beta (TGF-beta) family causes the inner walls of the vein to become too thick, slowing down or sometimes even blocking the blood flow that the graft was intended to restore. Inhibition of the TGF-beta signaling pathway reduced overgrowth in the grafted veins.

The team identified similar properties in samples of clogged human vein grafts, suggesting that select drugs might be useful in reducing vein-graft failure in humans.

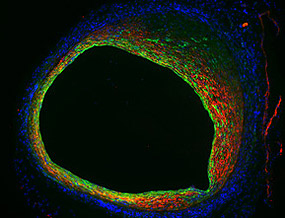

COURTESY: NHLBI

Endothelial cells not only form the inner lining of a blood vessel, but also contribute to blood-vessel narrowing as shown in this mouse vein-graft model. Endothelial cells (green) lose their typical morphology and become more like smooth-muscle cells (red). This change in cellular properties indicates that endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT) is operative in vein-graft stenosis.

Bypass surgery to restore blood flow hindered by clogged arteries is a common procedure in the United States. The great saphenous vein, which is the large vein running up the length of the leg, often is used as the bypass conduit due to its size and the ease of removing a small segment. After grafting, the implanted vein remodels to become more arterial; veins have thinner walls than arteries and can handle less blood pressure. However, the remodeling can go awry, and the vein can become too thick, resulting in a recurrence of clogged blood flow. About 40 percent of vein grafts experience such a failure within 18 months.

The researchers examined veins from mouse models of bypass surgery and discovered that a process known as an endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, or EndoMT, causes the inside of the vein to over-thicken. During EndoMT, many of the endothelial cells that line the inner surface of the vein proliferate and convert into more fibrous and musclelike cells and cause narrowing of the vessel.

This process was triggered by TGF-beta, a secreted protein that controls the proliferation and maturation of a host of cell types; the researchers found that TGF-beta becomes highly expressed just a few hours after graft surgery, indicating the remodeling starts quickly. The team also looked at human veins taken from failed bypass operations and found corroborating evidence for a role for EndoMT in human graft failure. In short-term grafts (those that survived less than one year), many of the cells inside the human veins displayed both endothelial and mesenchymal cell characteristics, whereas in long-term grafts (those that lasted more than six years) the cells on the inner wall were primarily mesenchymal in nature.

Now that the researchers better understand the mechanism that causes the abnormal thickening, they can look for therapeutic strategies to attenuate it and so reduce the number of bypass reoperations needed each year. (NHLBI authors: J. Nevado, D. Yang, C. St. Hilaire, A. Negro, F. Fang, G. Chen, H. San, A.D. Walts, R.L. Schwartzbeck, B. Taylor, J.D. Lanzer, A. Wragg, A. Elagha, L.E. Beltran, C. Berry, J.C. Kovacic, M. Boehm, Sci Transl Med 6:227ra34, 2014)

NICHD: HIGH PLASTICIZER LEVELS IN MALES LINKED TO DELAYED PREGNANCY FOR FEMALE PARTNERS

Women whose male partners have high concentrations of three common forms of phthalates, chemicals found in a wide range of consumer products, take longer to become pregnant than women in couples in which the male does not have high concentrations of the chemicals, according to researchers at NICHD and other institutions.

The researchers assessed the concentrations of phthalates and bisphenol A (BPA) in couples trying to achieve pregnancy. Phthalates, sometimes known as plasticizers, are used in the manufacture of plastics to make them more flexible. BPA is also used in plastics, including in some food and drink packaging.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, pthalates are used in hundreds of products such as fragrances, shampoos, nail polish, and plastic film and sheets. For the most part, people are exposed to phthalates by eating and drinking foods that have been in contact with containers and products containing the compounds. BPA is used to make some types of plastic containers and is found in the protective lining of food cans and other products.

The study authors measured urine concentrations of BPA and 14 phthalate compounds in couples trying to achieve pregnancy. Many phthalates are broken down and chemically changed before they are excreted from the body. Pregnancy took the most time to achieve in couples in which the males had high concentrations of monomethyl phthalate, monobutyl phthalate, and monobenzyl phthalate. Neither male nor female exposure to BPA was associated with pregnancy rates.

Because the researchers examined only the time it took to achieve pregnancy, the study could not determine precisely how the compounds might affect fertility. Future studies, the authors wrote, would be needed to determine whether the compounds affected particular aspects of reproductive health, such as hormone concentrations.

Enrolled in the study were 501 couples from Michigan and Texas from 2005 to 2009; the women ranged from 18 to 44 years of age and the men were over 18; the couples were not being treated for infertility but were trying to conceive a child. The couples were part of the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment (LIFE) study, established to examine the relationship between fertility and exposure to environmental chemicals and lifestyle. Previous analyses from the LIFE study found that high concentrations of polychlorinated biphenyls as well as of lead and cadmium also were linked to delayed pregnancy. (NICHD authors: G.M. Buck Louis, Z. Chen, R. Sundaram, L. Sun, Fertil Steril 100:162–169.e2, 2013)

NIDDK: RESEARCHERS BETTER UNDERSTAND RECEPTORS THROUGH NOVEL MOUSE MODEL

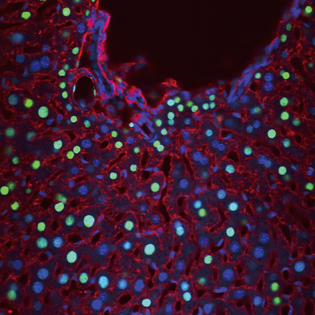

JENNIFER BERGNER AND MARI KONO, NIDDK

Cells that have been activated through the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (green nuclei) are shown in this liver section from SIP1–green fluorescent protein reporter mice. Immunofluorescent labeling of albumin (red) identifies hepatocytes. Staining with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue) indicates cell nuclei.

A team of NIDDK scientists have discovered a way to better comprehend how certain receptors work. The scientists created the first mouse model enabling them to detect cells in which a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) has been triggered. In this case, the specific GPCR recognizes a lipid signal called sphingosine-1-phosphate, important for controlling inflammation, a process that occurs when the body is injured.

GPCRs are not only triggered by environmental signals related to tastes, odors, invading pathogens, and more but are also targets for nearly half of all medications used today. The new mouse model not only will allow a better understanding of how GPCRs work in the body but also may help in the development of new medicines to combat diseases in which inflammation is involved. (NIDDK authors: M. Kono, A.E. Tucker, J. Tran, J.B. Bergner, E.M. Turner, R.L. Proia, J Clin Invest DOI:10.1172/JCI71194)

NIEHS: PREVALENCE OF ALLERGIES THE SAME, REGARDLESS OF WHERE YOU LIVE

In the largest, most comprehensive nationwide study to examine the prevalence of allergies from early childhood to old age, NIEHS scientists reported that allergy prevalence is the same across different regions of the United States, except in children five years old and younger. Allergists would have predicted that allergy prevalence varied depending on where people live. This study, however, suggests that people prone to developing allergies are going to develop an allergy to whatever is in their environment.

The research is the result of analyses performed on blood serum data compiled from approximately 10,000 Americans in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2006. Although the study found that the overall prevalence of allergies did not differ among regions, researchers discovered that one group of participants did exhibit a regional response to allergens. Among children aged one to five, those from the southern United States displayed a higher prevalence of allergies than their peers living in other U.S. regions.

The higher allergy prevalence among the youngest children in Southern states seemed to be attributable to dust mites and cockroaches, the researchers explained. As children get older, both indoor and outdoor allergies become more common, and the difference in the overall prevalence of allergies fades away.The NHANES 2005–2006 not only tested more allergens across a wider age range than prior NHANES studies, but also provided quantitative information on the extent of allergic sensitization. The survey analyzed serum for nine different antibodies in children aged one to five years and 19 different antibodies in subjects 6 years and older. Previous NHANES studies used skin-prick tests to test for allergies.

The scientists determined risk factors that made a person more likely to be allergic. The study found that in the six-years-and-older group, males, non-Hispanic blacks, and those who avoided pets had an increased chance of having allergen-specific immunoglobulin E antibodies, the common hallmark of allergies. Socioeconomic status (SES) did not predict allergies, but people in higher SES groups were more commonly allergic to dogs and cats, whereas those in lower SES groups were more commonly allergic to shrimp and cockroaches.

By generating a more complete picture of U.S. allergen sensitivity, the team uncovered regional differences in the prevalence of specific types of allergies. Sensitization to indoor allergens was more prevalent in the South, whereas sensitivity to outdoor allergens was more common in the West. Food allergies among those six years and older were also highest in the South.

The researchers anticipate using more NHANES 2005–2006 data to examine questions allergists have been asking for decades. For example, using dust samples obtained from subjects’ homes, the group plans to examine the link between allergen exposure and disease outcomes in a large representative sample of the U.S. population. (NIEHS authors: P.M. Salo, J.A. Hoppin, P.J. Gergen, D.C. Zeldin, J Allergy Clin Immunol DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1071)

NICHD: ASPIRIN DOES NOT PREVENT PREGNANCY LOSS

A daily low dose of aspirin does not appear to prevent subsequent pregnancy loss among women with a history of one or two prior pregnancy losses, according to NICHD researchers. However, in a smaller group of women who had experienced a single recent pregnancy loss, aspirin increased the likelihood of becoming pregnant and having a live birth.

Many health-care providers prescribe low-dose aspirin therapy for women who have had a pregnancy loss (miscarriage or stillbirth) and who would like to get pregnant again. However, the effectiveness of this treatment has not been proven, the researchers wrote.

In the largest study of its kind, the researchers, who collaborated with investigators from other institutions, randomly assigned more than 1,000 women with a history of pregnancy loss to either daily low-dose aspirin or a placebo. The women began taking the equivalent of one low-dose aspirin (81 milligrams) each day while trying to conceive. The researchers reported that, overall, there was no difference in pregnancy-loss rates between the two groups.

The study authors hypothesized that aspirin therapy might increase the conception rate by increasing blood flow to the uterus. The researchers called for additional research to determine whether aspirin therapy might be helpful for improving fertility in other subgroups as well, such as women who can’t establish a pregnancy because the embryo fails to implant in the uterus. (NICHD authors: E.F. Schisterman, N.J. Perkins, S.L. Mumford, Lancet DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60157-4)

EXCERPT FROM A LETTER FROM DR. STEPHEN I. KATZ: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE NIAMS INTRAMURAL RESEARCH PROGRAM

February 2014

http://www.niams.nih.gov/News_and_Events/NIAMS_Update/2014/highlights_irp.asp

I am proud to say that over the past year, two drugs have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) based in part on research from the NIAMS IRP. The first, tofacitinib (brand name Xeljanz), was developed through a public-private partnership between Dr. John O’Shea and the pharmaceutical company Pfizer. In the early 1990’s, Dr. O’Shea’s research group identified a group of proteins, called Janus kinases, that are important in regulating the human immune system, and they hypothesized that blocking the proteins might protect against the damaging inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and certain other autoimmune diseases. After many years of collaborative research, a new class of drugs targeting Janus kinases exists. Tofacitinib is a member of this new class, and is the first new drug in more than a decade that can be taken as a pill, rather than an injection, to slow or halt RA joint damage. Many clinical studies are now being pursued to explore the use of this drug in the treatment of psoriasis and many other inflammatory diseases.

The second FDA approval was for the new use of an established drug to treat a rare genetic disease in children. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease (NOMID) is a rare, debilitating disease that strikes within the first weeks of life. If left untreated, children with NOMID may develop hearing and vision loss, cognitive impairment, and physical disability. Previous work by NIAMS IRP clinical researcher Raphaela Goldbach-Mansky, M.D., M.H.S., Acting Chief of the Translational Autoinflammatory Disease Section, showed that the symptoms of NOMID were facilitated through the immune system’s interleukin-1 (IL-1) signaling pathway, and that blocking IL-1 with the FDA-approved RA drug anakinra relieved symptoms of NOMID. Recently, Dr. Goldbach-Mansky and her team conducted a successful clinical trial demonstrating that anakinra not only improved the signs and symptoms of NOMID, but also worked over the long-term to stop the progression of organ damage. Based on the trial’s results, anakinra has become the first FDA-approved treatment for NOMID.

CONTRIBUTOR: KRYSTEN CARRERA, NIDDK

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 27, 2022