Open SESAME: A New Way to Clear the Heart’s Passageways

Minimally Invasive Procedure Provides Help for Ailing Hearts

IRP physician-scientists and their collaborators outside NIH have invented a new way to access the heart in order to treat serious heart problems.

In the story of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, two magic words were necessary to open the cave where treasure was hidden. At NIH, researchers are applying those same special words, ‘open sesame,’ to unlock a chamber that is similarly difficult to access. In this case, however, it’s the left ventricle of the human heart.

“Enter one of the greatest acronyms in medicine: Open SESAME,” says IRP senior investigator Robert Lederman, M.D., who leads the IRP’s Laboratory of Cardiovascular Intervention. “That’s what we’re doing: opening up space in the heart.”

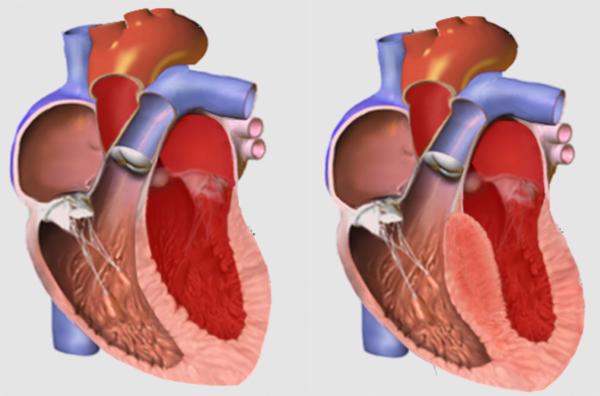

The SESAME approach, which stands for SEptal scoring Along Midline Endocardium, is a new technique invented through a collaboration between Dr. Lederman’s IRP team and researchers at Emory University. The procedure is designed to treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a common inherited condition in which the walls of the heart grow so muscular and thick that blood can’t be adequately pumped through the heart to fulfil the body’s needs. It typically affects the wall, or ‘septum,’ between the heart’s two bottom chambers, the left and right ventricles.

A normal septum (left) compared to a thickened septum (right), which can stymie blood flow. Image credit: Npatchett via English Wikipedia

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy affects an estimated 1 in 500 Americans, although the actual numbers may be higher. Though it varies in severity, the condition can cause shortness of breath, chest pain, dizziness, and fainting spells. Over time, severe cases can lead to heart failure. It is also the most common cause of left ventricle outflow tract (LVOT) obstruction, in which blood is blocked from exiting the heart’s final chamber by the thickened left ventricle.

In cases where hypertrophic cardiomyopathy causes an obstruction of blood flow, several treatments exist, but none are truly satisfactory. In the 1960s, Andrew Glenn Morrow, M.D., a senior surgeon at NIH whose family was affected by a particularly aggressive form of the disease, and NIH cardiologist Eugene Braunwald, M.D., developed a surgical approach to treat the disease called septal myectomy. The procedure clears the obstruction by opening up the heart and cutting a little divot into the heart muscle.

“It’s really difficult surgery,” Dr. Lederman says. “It’s extremely difficult to see what you’re doing, and even though this procedure has become standard treatment for LVOT, most medical centers in North America have disappointing surgical results with it because you need a high volume of patients to get enough experience and most centers only do one or two of these procedures a year.”

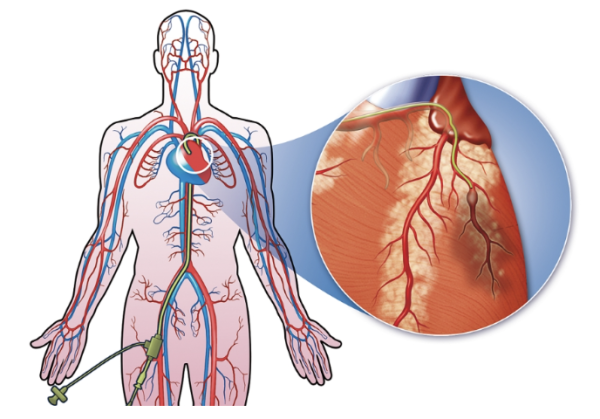

In the 1990s, researchers in the U.K. developed a non-surgical alternative called alcohol septal ablation. In this procedure, doctors use a small tube, called a catheter, threaded through an artery into the chamber of the heart. Next, they drip ethanol into the heart, which causes a controlled heart attack and thus kills off some of the excess cardiac muscle tissue causing the obstruction.

Modern heart surgery often uses a small tube called a catheter, which can be inserted through a small incision and threaded through blood vessels all the way to the heart. In this illustration, the catheter is inserted into the leg.

“The problem is that nature did not anticipate this procedure, and it relies on a certain amount of serendipity,” Dr. Lederman says, because patients need to have an artery going to just the right place in the heart to hit the obstruction in order for it to work, and they don’t always have one. “It usually doesn’t hit the right place or, worse, the heart attack affects and damages tissue in the heart’s conduction system, which controls the rhythm of its beat, so patients end up needing a permanent pacemaker afterward.”

Medications that reduce the obstruction in the heart, on the other hand, provide a non-invasive option. Unfortunately, they have considerable side effects and can cost up to $100,000 a year, putting them out of reach for many patients.

The prominent downsides of all the existing options for treating hypertrophic cardiomyopathy spurred Dr. Lederman and his collaborators to develop SESAME, which uses catheters to thread electrical wires into the heart — one through an artery into the heart’s chamber and one directly into the heart muscle itself. When the wires join, they create an electrical circuit within the heart muscle, which produces heat that burns through the excess cardiac tissue to thin it out and reduce the obstruction. Using a combination of X-ray and sonogram to see inside the body, cardiologists precisely place the wire and avoid touching important electrical conducting tissue in the heart.

“We figured out a way to navigate, not in the open spaces of the blood vessels and heart chambers, but actually inside the muscle of the beating heart,” Dr. Lederman explains. “We can hunt around inside the heart muscle. It’s one of the coolest things ever, if I do say so myself."

Dr. Robert Lederman led NIH’s contributions to the invention of SESAME.

Dr. Lederman notes this procedure has the potential to help patients with other heart problems as well. For example, people who need their mitral valve replaced may be too sick or too small to undergo the procedure and receive the replacement valve, which can be bulky.

“The replacement valve can actually cause an obstruction, which can be fatal,” he says, “so many women, since they typically have smaller hearts, aren’t eligible. SESAME can create more space for aortic and mitral valve replacement in that situation.”

While SESAME is still an extremely difficult procedure, just like its precursor septal myectomy, Dr. Lederman’s collaborators are hard at work perfecting it. Those collaborators include Emory University’s Adam Greenbaum, M.D., and Vasilis Babaliaros, M.D., as well as Jaffar Khan, M.D., at St. Francis Hospital in Roslyn, New York. So far, all of the patients who have undergone the procedure were in an emergency situation with no better option, but Dr. Lederman and his colleagues recently received approval to begin a true clinical trial of the technique. In addition, they are working with a small business called SESAME, Inc., to develop a device that will make the procedure easier so more cardiologists can perform it.

“This is an opportunity for NIH to fund early-stage companies in this market despite the perceived high risk,” Dr, Lederman says.

“Working in the Intramural Program gives us enormous creative and academic freedom,” he adds. “No project like SESAME would ever get prospective grant funding from NIH outside of the Program. It's only because of the unique organization of the NIH IRP where we're funded ahead of the study and reviewed when we complete it that I'm able to come up with useful procedures like this over and over and over again.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Greenbaum AB, Ueyama HA, Gleason PT, Khan JM, Bruce CG, Halaby RN, Rogers T, Hanzel GS, Xie JX, Byku I, Guyton RA, Grubb KJ, Lisko JC, Shekiladze N, Inci EK, Grier EA, Paone G, McCabe JM, Lederman RJ, Babaliaros VC. Transcatheter Myotomy to Reduce Left Ventricular Outflow Obstruction.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024 Apr 9;83(14):1257-1272. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.02.007.

[2] Khan JM, Bruce CG, Greenbaum AB, Babaliaros VC, Jaimes AE, Schenke WH, Ramasawmy R, Seemann F, Herzka DA, Rogers T, Eckhaus MA, Campbell-Washburn A, Guyton RA, Lederman RJ. Transcatheter myotomy to relieve left ventricular outflow tract obstruction: the septal scoring along the midline endocardium procedure in animals. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022 Jun;15(6):e011686. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.121.011686.

[3] Greenbaum AB, Khan JM, Bruce CG, Hanzel GS, Gleason PT, Kohli K, Inci EK, Guyton RA, Paone G, Rogers T, Lederman RJ, Babaliaros VC. Transcatheter myotomy to treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and enable transcatheter mitral valve replacement: first-in-human report of septal scoring along the midline endocardium. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022 Jun;15(6):e012106. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.122.012106.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Thursday, September 26, 2024