Celebrating Black Scientists’ Contributions to IRP Research

NIH’s Historical Archives Highlight Numerous Prominent Scientists

Diversity is a cornerstone of innovation and scientific discovery. Through initiatives like its Distinguished Scholars Program and the Independent Research Scholars Program, the IRP hopes to recruit more scientists from groups historically under-represented in biomedical research, including African American and other Black researchers. As the IRP works towards a more diverse future, let’s celebrate Black History Month by delving into the archives of the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum to learn about some of the Black scientists who have made important contributions to an array of IRP discoveries.

The photo below was taken in 1963 and shows the Laboratory of Biochemistry at the National Heart Institute, which would later become the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). The photo includes two Black women trailblazers, Mary G. Burroughs (front row, right) and Juanita P. Cooke (front row, second from left). Neither Cooke nor Burroughs had a M.D. or Ph.D., as such degrees were very rare for Black women at that time. However, that did not stop them from playing a vital role in IRP research.

For instance, Cooke, who joined NIH in 1952 as a chemist, worked with Dr. Christian Anfinsen and was named as a contributor to the studies on protein folding that earned Dr. Anfinsen the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. While continuing her work in the lab, Cooke became an Equal Employment Opportunity representative in the 1970s. She was the first NIH employee to receive an Equal Opportunity Achievement Award from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Dr. Alma LeVant Hayden was passionate about chemistry. She earned her master’s degree in chemistry at Howard University before joining the National Institute of Arthritic and Metabolic Diseases, now known as the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), in 1951. She became well-versed in cutting-edge chemical analysis techniques, including paper chromatography, which she demonstrates in the photo below. She also became a nationally recognized expert in spectrophotometry, which uses light to reveal information about the molecules in a sample. In 1956, she left NIH for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), where she rose to lead the Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry’s Spectrophotometry Branch. At the time of her hiring, she was likely the first Black scientist at the FDA.

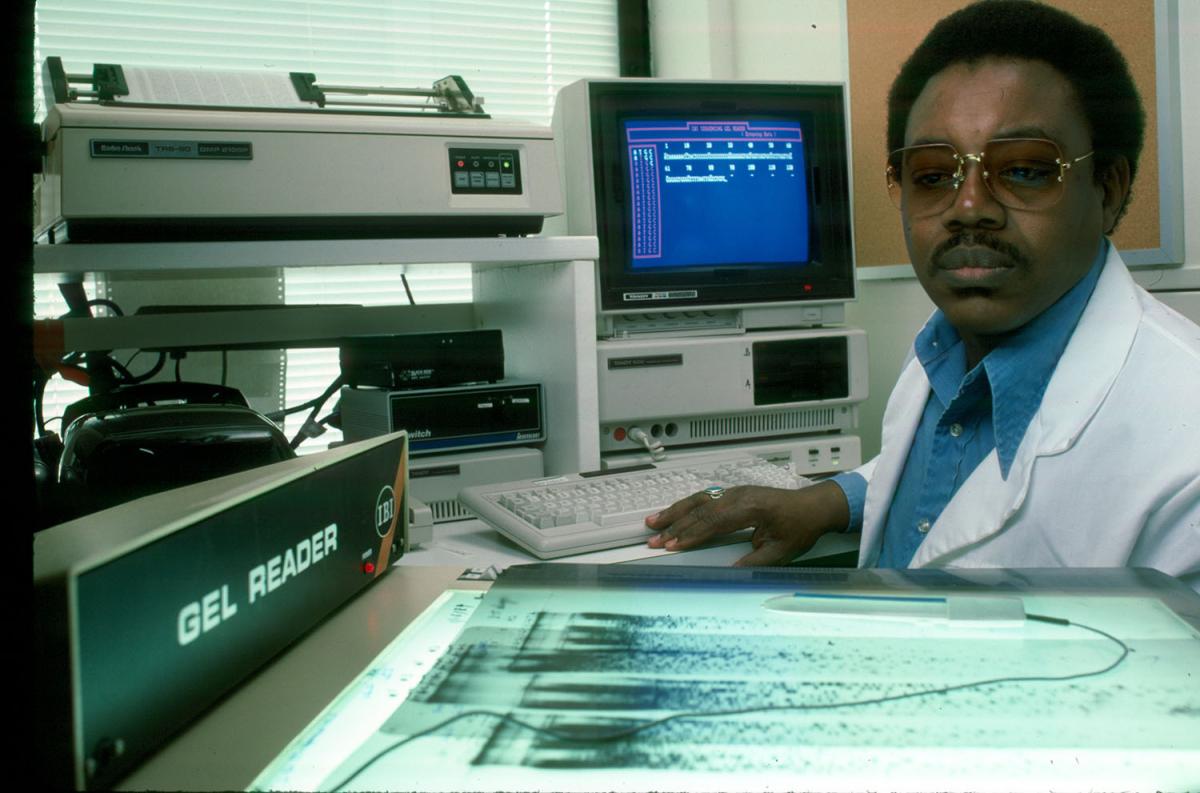

Dr. William Coleman Jr. excelled at research and administration during his 40 years at NIH. While a scientist at NIDDK, Dr. Coleman studied Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that causes stomach infections, using technology like the DNA gel reader seen in this photo. He would later become the IRP’s first Black Scientific Director when he took the position at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) in 2011. He balanced his roles at NIDDK and NIHMD while developing mentorship programs and advocating for workplace diversity.

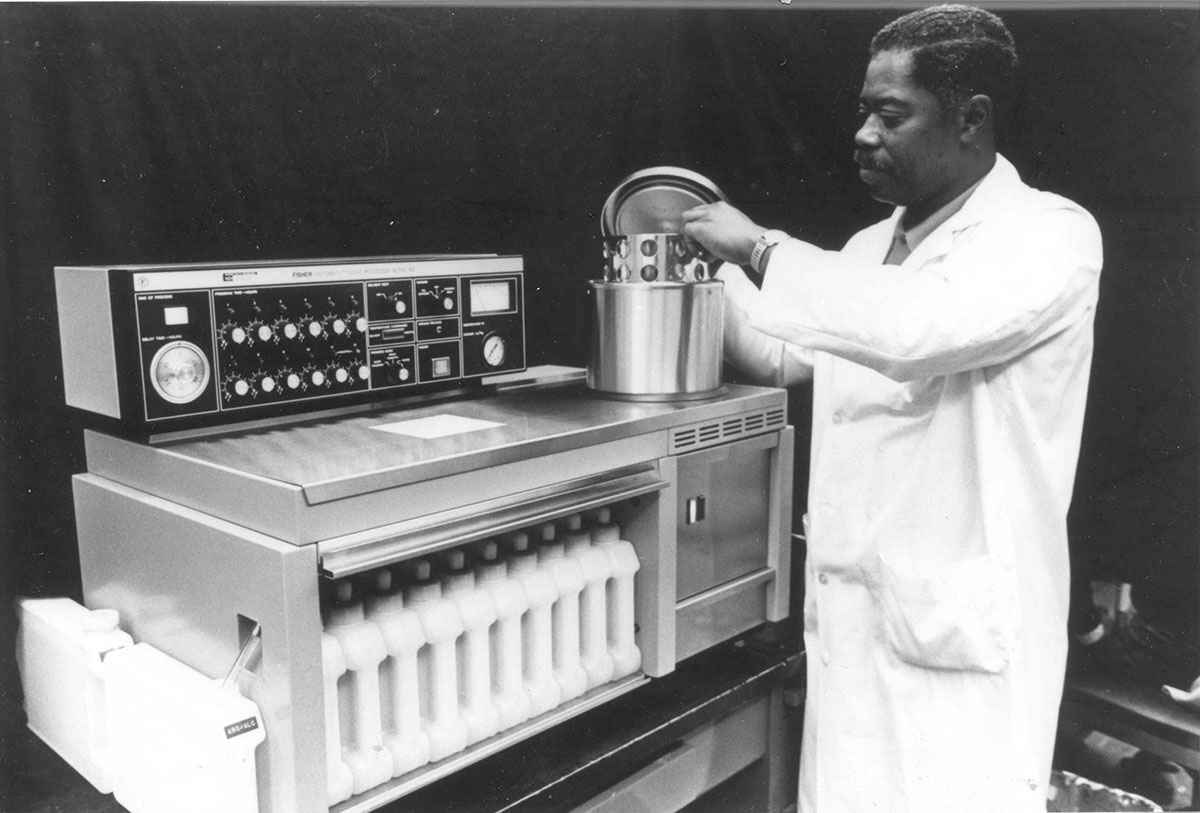

Of course, not all scientists who enable IRP breakthroughs gain wide-spread name recognition like those mentioned previously. The archives of the Stetten Museum include many photos of scientists who have worked in the IRP over the years but whose names are unknown. For example, this photo from the early 1980s shows a laboratory technician from the Laboratory of Pathology at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) loading a histomatic tissue processor, a machine that could simultaneously test hundreds of tissue samples for many different types of cancer. Without the work of such individuals, many important discoveries may not have been made.

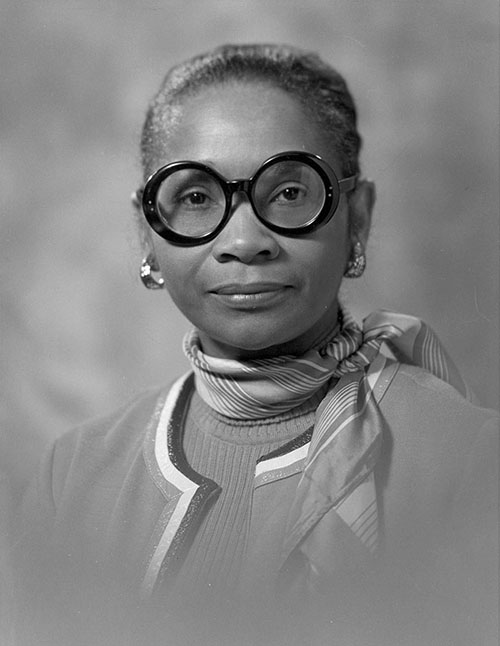

Dr. Clarice Reid didn’t start out studying sickle cell anemia. A pediatrician by training, she transitioned to public health in the early 1970s. When she joined NHLBI in 1973, she began working on the Sickle Cell Disease Program, a national program established by an act of Congress to educate, support, and treat those living with sickle cell. As Chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch, she spearheaded important advancements in research and treatment. In 1994, she was named director of NHLBI’s Division of Blood Diseases and Resources.

NIH historians are fortunate to have sat down for two oral histories interviews with Dr. Reid. In the more recent interview, she shared her perspective on her career after retiring in 2018.

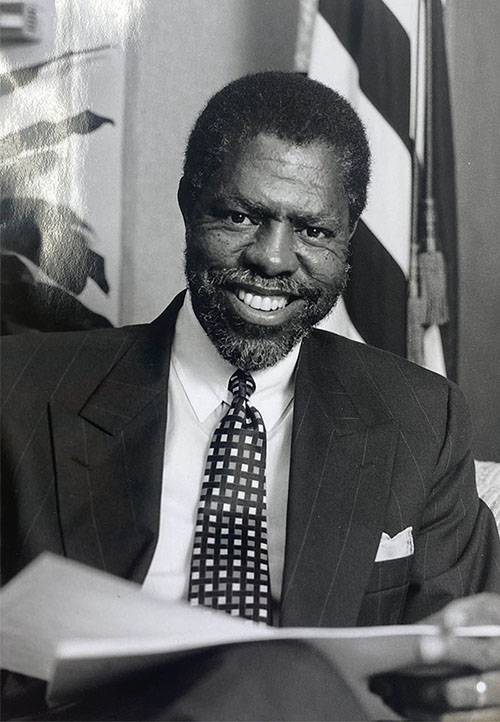

Dr. Kenneth Olden was the Director of the National Toxicology Program and Director of NIH’s National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) from 1991-2005. Before that, he was Director of the Howard University Cancer Center and Chairman of their Department of Oncology. With his expertise in cancer and cell biology, he helped uncover environmental causes of cancer and showed that social determinants of health, like poverty and discrimination, influenced negative environmental health outcomes.

In his oral history with the Office of NIH History, he shared the perspective of public health researchers who want to make sure they’re keeping the public safe, saying, “I want to know that I’m really impacting peoples’ lives…I want my science utilized.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024