Celebrating Black History at NIH

NIH History Office Highlights Contributions of Black Employees

Every February, we celebrate Black History Month to spotlight the huge contributions Black Americans have made to our nation’s culture, as well as commemorate their ongoing fight for fair treatment under the law. Just as Black individuals have had tremendous influence on the U.S. as a whole, they have also achieved great things at NIH, demonstrating the critical importance of diversity within the scientific community.

In honor of Black History Month, we’re highlighting people and programs that championed diversity at NIH. Read on to learn about just a few examples of how diversity has evolved at NIH and how Black employees have helped advance its mission.

The history of women and minorities at NIH is the focus of an upcoming exhibit the Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum is planning for late 2022, which is tentatively titled “#Shadowwork.” Shadow work is the term for exploring the unpleasant past in an individual’s or institution’s history, such as segregation or colonialization, so that movement forward can begin. Because only a sliver of such a broad topic can be captured in six small display cases, the trending social media hashtag (#) is used in the title to signal that this display will cover only the tip of the iceberg on the topic.

This photo, taken just before NIH moved to its Bethesda campus, reveals the demographics of the 1930s workplace. Through images like this one, the exhibit will highlight the stories of early Black employees like Roskey Jennings, pictured here in the back standing before the left column, which help tell the complete, diverse history of NIH.

This photo of the staff of the NIH Director’s office was taken in 1937 on the steps of the Administration Building at the old NIH campus in Washington, D.C., shortly before they moved to Building 1 on NIH's current campus in Bethesda, Maryland.

At the time of his death in 1996, Jennings had worked at NIH for over 66 years and proudly held length of service records for both NIH and the Department of Health and Human Services. Jennings was present at NIH from the beginning, working at its precursor, the Hygienic Laboratory, on 25th and E St. NW in Washington, D.C. He watched the construction of Building 1 and worked under 13 NIH directors. He also remembers the impact of segregation on the early campus, saying of NIH baseball teams until 1949 that “colored people were not allowed to play” on the same team as whites. He was recognized not only for his dedication to his job, but also his positive and friendly attitude. At NIH’s 1979 Black History Observance, he was acknowledged for his contribution to Equal Employment Opportunity.

This photo of Roskey Jennings comes from his obituary in the November 19, 1996 edition of the NIH Record.

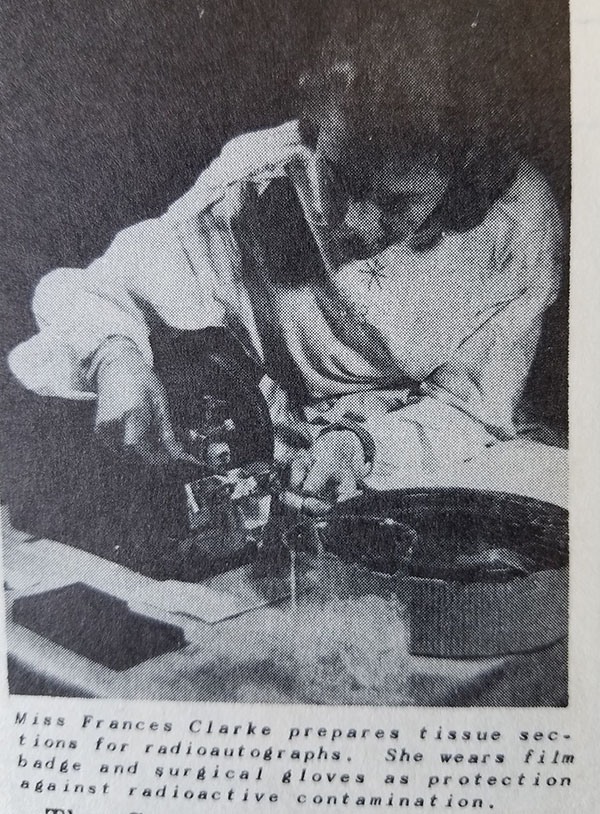

The first Black woman pictured in the NIH Record was Frances A. Clark. Her photo was featured on November 11, 1949 for an article titled “Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases.” She’s shown preparing tissue for radioautographs, a process where radioactive materials produce an image on film. Clark studied the immune system in the Experimental Biology and Medicine Institute (EMBI), which was later folded into the entity that would become the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

This photo from the November 11, 1949 edition of the NIH Record was the first to depict a Black woman. In it, NIH researcher Frances A. Clark prepares tissue sections for radioautographs.

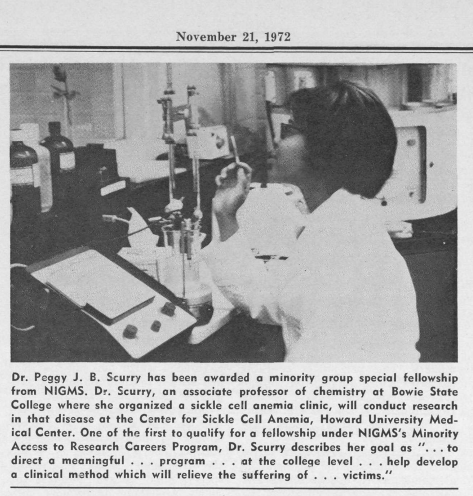

This photo from the November 21, 1972 edition of the NIH Record shows Dr. Peggy J. B. Scurry, who was awarded one of the first MARC fellowships.

In 1972, NIH’s National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) established the Minority Access to Research Careers (MARC) Program, a step which was “urgently needed to help correct the extreme imbalance in the United States of the numbers of minority group health scientists and teachers with doctoral degrees,” according to NIH’s Dr. DeWitt Stetten Jr., the namesake for the NIH Stetten Museum and a renowned medical educator and researcher who served as NIH’s deputy director for science and as senior scientific advisor to the NIH Director in the 1970s and 1980s. The MARC program provided fellowships to science educators at colleges and universities that served predominantly minority communities with the goal of diversifying the individuals with an M.D. or a Ph.D. in a scientific discipline.

Dr. Peggy J. B. Scurry was awarded one of the first fellowships under the MARC Program. In its first year, the program awarded 12 fellowships to teachers and research scientists. An associate professor of chemistry at Bowie State College, she would conduct research on sickle cell anemia at Howard University Medical Center. In 1977, she received her medical doctorate from Howard, a historically black college, and is now an OB/GYN in Silver Spring, Maryland.

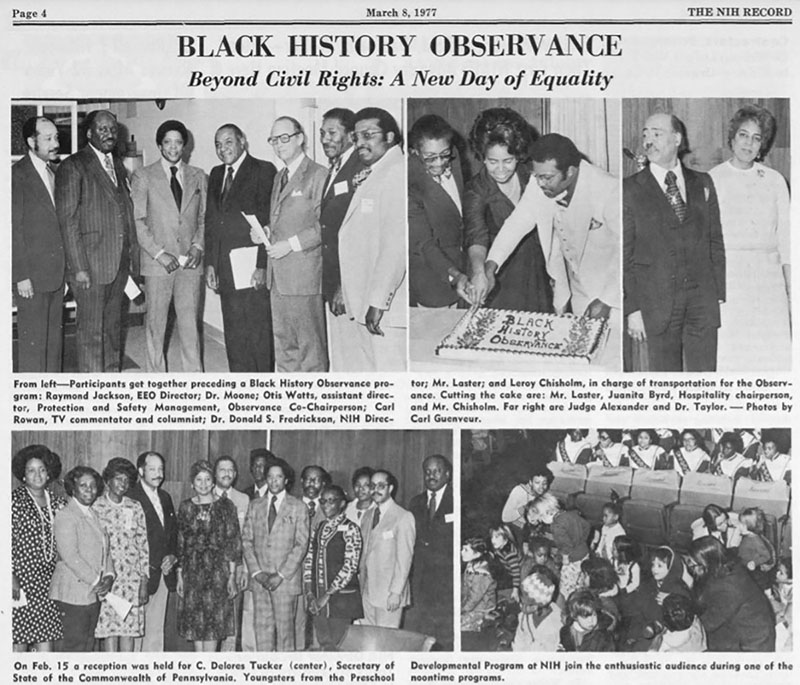

While we might not be able to gather in person this year for a celebration, the NIH Record gives us a glimpse of previous Black History Month Observances at NIH. This article shows the 1977 celebration, which featured a week of speakers that included Judge Harry T. Alexander, D.C. NAACP president and retired Superior Court Judge, and Dr. Estelle Taylor, chairman of the department of English and the Division of Arts and Humanities at Howard University. The 1977 celebration was the sixth annual observance of Black History Month held by NIH.

These photos from NIH's 1977 Black History Month celebration were published in the March 8, 1977 edition of the NIH Record.

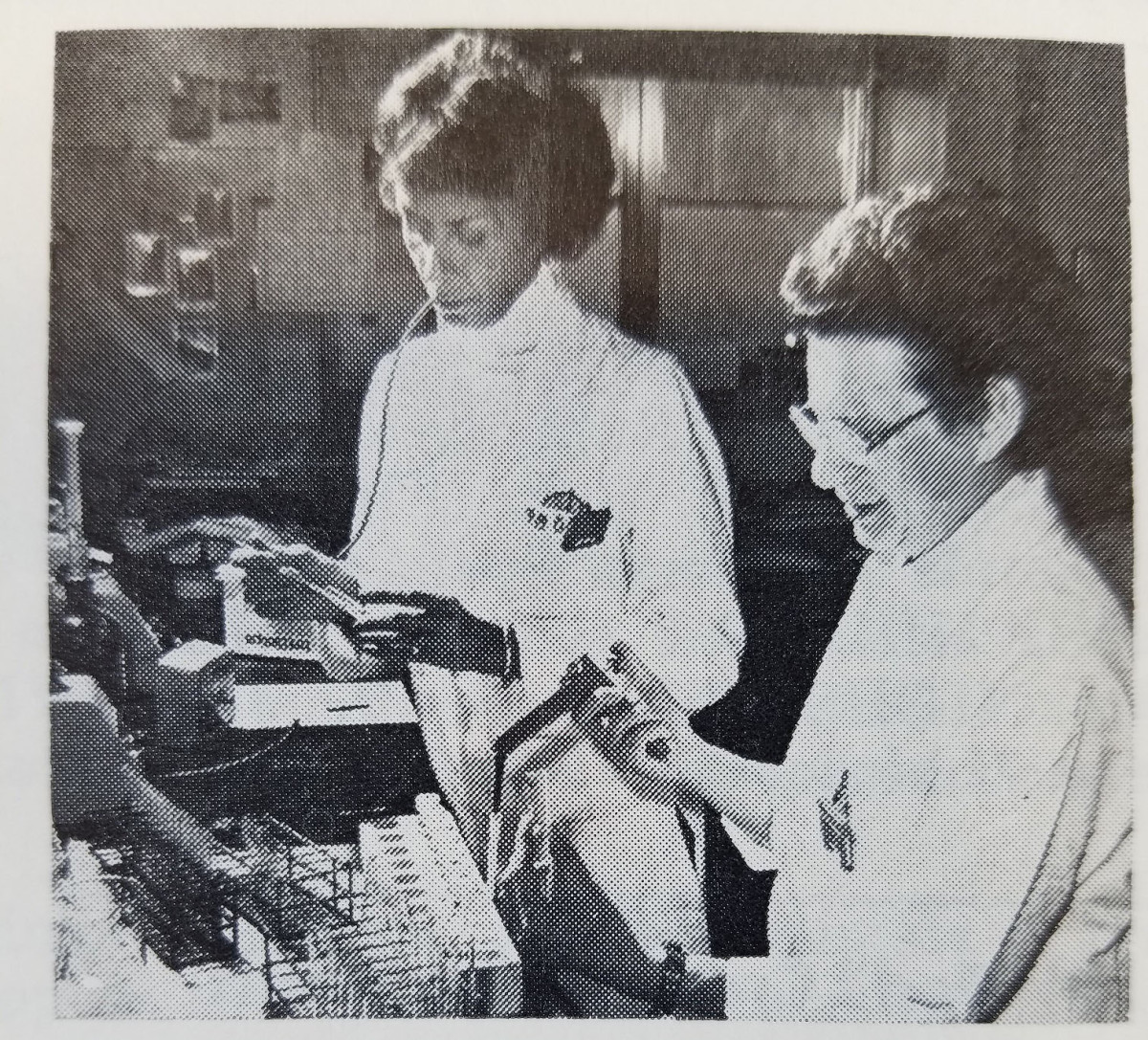

The story of Clara W. Hall (left) is a familiar one to people of color. A research chemist at the National Institute of Arthritis, Metabolism and Digestive Diseases, which later became NIDDK, Hall worked with Dr. Elizabeth Neufeld (right) studying genetic conditions affecting lysosomes, which serve as the garbagemen of the cell. These disorders can cause skeletal abnormalities, intellectual disabilities, and a shortened lifespan. In 1982, the duo’s research earned Dr. Neufeld the Albert Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research, the American version of the Nobel Prize. Dr. Neufeld did not want her colleague’s work to go unrecognized, but Hall never received an award. As well as being a chemist, Hall was a classically trained pianist and cellist and a dedicated tennis fan. She retired in 1999.

This photo of Clara W. Hall (left) and Dr. Elizabeth Neufeld was published in the November 11, 1975 edition of the NIH Record.

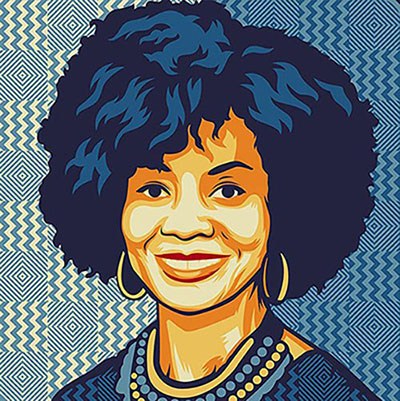

While NIH has made considerable strides over the last century towards increasing the diversity of its workforce and supporting researchers from groups traditionally under-represented in the sciences, there is still a lot of work left to do in this area. Recently, NIH’s UNITE initiative created the Power of an Inclusive Workplace Recognition Project to acknowledge and emphasize the diversity of identities and experiences represented at NIH. The project was inspired by IRP investigator Sadhana Jackson, M.D., a pediatric neurooncologist. Noticing the lack of diversity in portraiture around NIH, she worked with UNITE to create more representative imagery. That collaboration led to the creation of posters featuring portraits like this one of Erika Boone, Ph.D., acting director of NIH’s Division of Biomedical Research Workforce and director of Loan Repayment. The program is just one of many current initiatives at NIH aimed at growing and showcasing diversity. To view the program’s posters, including the one featuring Dr. Boone, visit the NIH Flickr page.

This portrait of Dr. Erika Boone is one example of the imagery highlighted by NIH’s Power of an Inclusive Workplace Recognition Project.

Black Americans have been historically under-represented in the sciences, and NIH clearly was no exception. However, through a deliberate focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion, the Intramural Research Program has made great strides in providing opportunities for people of color both inside and outside the lab. By collecting images and news clippings from throughout NIH’s long and storied past, the Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum not only provides modern audiences with a glimpse of what the work environment was like for NIH’s Black employees in the past, but also demonstrates the success of efforts to make NIH a more inclusive workplace. With the knowledge that such endeavors pay off, the IRP will continue striving to build upon them now and in the future.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024