NIH History Shows Off Its Spooky Side

Museum Collection Contains Many Eye-Catching Objects and Photographs

Anyone who has engaged in a marathon of gruesome Halloween movies knows that the human body can be portrayed in ways that are frightening. Even in real life, the tools and techniques researchers use to understand disease may seem like something out of a work of fiction. In honor of Halloween this year, let’s sneak inside the archives of the Office of NIH History & Stetten Museum to see the spookiest nooks and crannies of our collection. Whatever you do, don’t turn out the lights!

We’ll start with a classic: medical models. This is a model of a human head cut in half to reveal the inner workings of the brain, muscles, and blood vessels. Such models were created to help students learn anatomy without conducting human dissections, but this one, made by Clay-Adams Inc., was purchased by NIH Medical Arts in the 1990s so NIH artists could create more realistic anatomical drawings.

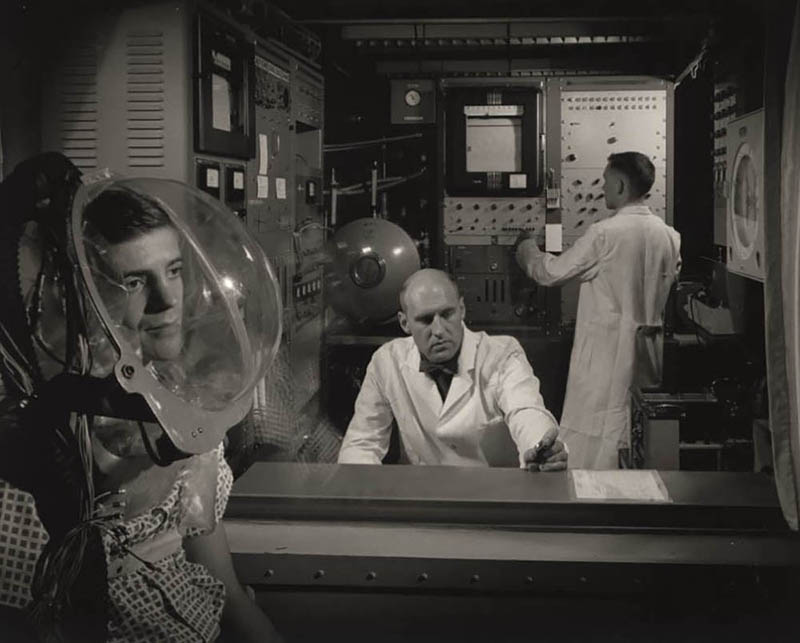

While it may look like something out of the Twilight Zone, this photo from our archival collection actually depicts important scientific research. From the 1950s through the 1970s, researchers at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, which would later become the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), used these hoods to collect data on oxygen consumption. That data was then used to study how the human body uses energy. This photo was taken by NIH photographer Jerry Hecht in the 1950s and is part of the Hecht photo collection.

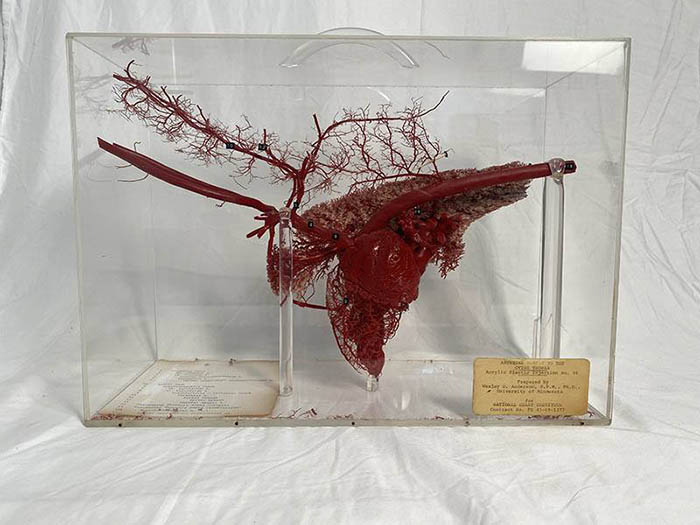

A heart in a case? Now how did they do that? This model of a sheep’s heart, lungs, and blood vessels was created in the 1960s by Dr. Wesley D. Anderson, a veterinarian at the University of Minnesota. He used a method of plasticization that results in a perfect plastic representation of internal structures and vessels. This model helped researchers with creating ‘ventricle assist devices,’ which help the heart pump blood after it has experienced damage.

What’s so spooky about this frog? Even if you don’t have ranidaphobia (frog phobia), you should be very wary of this little creature. Phyllobates aurotaenia is a species of poisonous frog native to the coast of Columbia. NIDDK biochemist John Daly, Ph.D., collected this specimen while studying the chemistry of poisons in the 1970s. Dr. Daly studied poisonous frogs to identify how their toxins affected and could possibly help humans. Through his research, Dr. Daly discovered the chemical compound epibatidine. While epibatidine reduces pain, it is 200 times more potent than morphine. For that reason, it was never developed into a therapeutic treatment, as it is deadly to humans even in small doses.

Can you guess what this is? It’s not a ghost! It’s a transparent mannequin made to test the first whole-body radiation counter, which was developed at NIH to detect the amount and location of radiation in the human body and installed in the NIH Clinical Center in 1962. The mannequin, named Christine, had several compartments where Dr. Howard L. Andrews, NIH Radiation Safety Officer (pictured left), and Dorothy Peterson, his assistant (pictured right), could add a known amount of radioactive isotope to test the machine’s accuracy. Learn more in this NIH Record article from 1962.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023