A Look Back at the Legacy of Theodor Kolobow

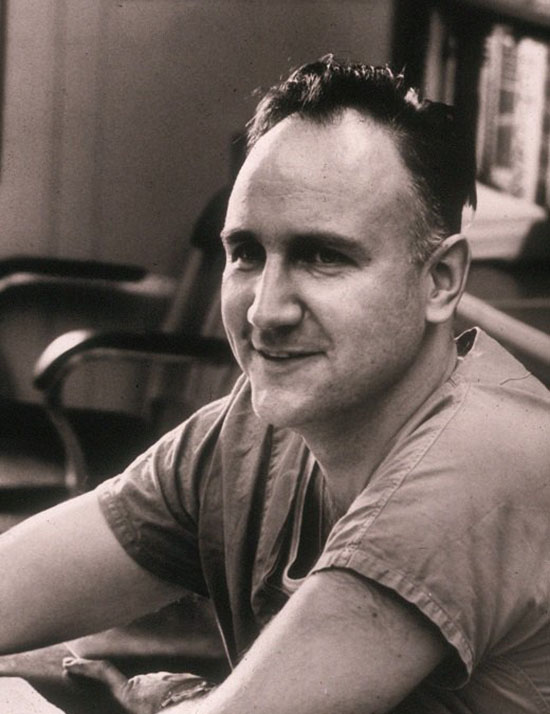

The IRP has been home to a number of truly remarkable scientists who spent decades making discoveries and developing technologies that would go on to improve the lives of many. One of these giants was Theodor Kolobow, M.D., who passed away in March of last year at age 87. During his many years at the NIH's National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), Dr. Kolobow made momentous contributions to the study of the lungs and cardiovascular system, including advancements in the development of artificial organs and key insights into the biological processes behind acute lung injury.

Dr. Kolobow's legacy lives on not only through his colleagues' fond memories and his lasting influence on medical practice, but also through the NIH's historical archives. Read on for a tour through Dr. Kolobow's life and career, as can only be told by the Office of NIH History.

Dr. Theodor Kolobow, whose “thinking was always outside the box simply because he never was in a box,” was born in Kardla, a village on an island in Estonia, in 1931. His father was a Russian Orthodox priest and lawyer, who gave Kolobow a deep religious and ethical sensibility. During World War II, his family fled the invading Russian army and spent the rest of the war in a refugee camp in Augsburg, Germany, where he learned to speak German, Russian, and English.

After the war, Dr. Kolobow helped Estonian refugees fill out immigration applications for the United States and decided that his educational opportunities lay there, too. He received a scholarship from Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio. When the Dean of Students met Kolobow, as he disembarked from an American troop ship in New York, Kolobow had $20 and his father’s crucifix in his pocket. He was still weeks from his 19th birthday.

- The above quote is from “Ted Kolobow,” Luciano Gattinoni, Antonio Pesenti, Lorenzo Berra, and Robert Bartlett, Intensive Care Medicine (2018) 44:551–552.

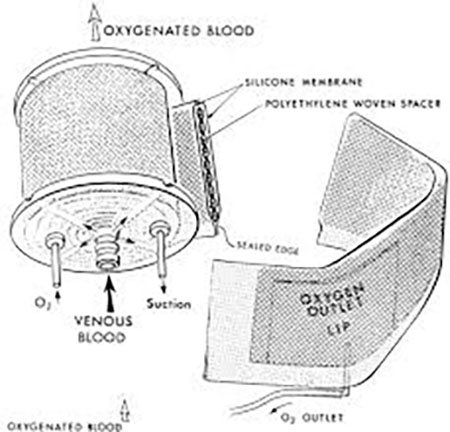

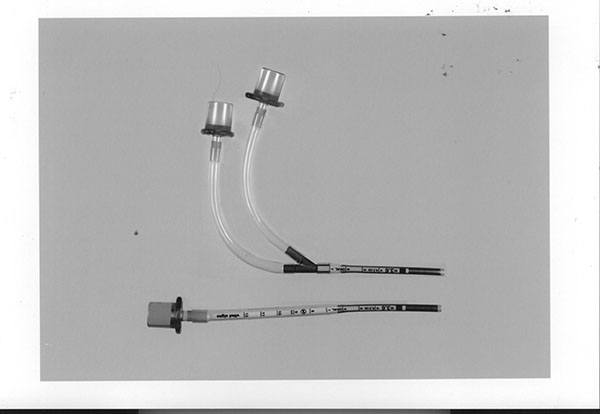

Required to do research as a medical student at Case Western Reserve University, Dr. Kolobow chose to work with Dr. George H.A. Clowes, a surgeon looking for ways to keep blood oxygenated during heart surgery. Dr. Kolobow, who loved to build things, developed a test to see which plastic membranes were the best at exchanging oxygen in the blood. He then coiled the membrane around a spindle, increasing the surface area of the membrane while decreasing the size of the device. He used suction to pull the blood through. Clowes included Dr. Kolobow’s name on the paper introducing the device to the American Society for Artificial Internal Organs in 1955. Now, Dr. Kolobow’s invention, called a membrane oxygenator (pictured above), is used in most ventilators.

After getting his M.D. in 1958, and completing his training at Cleveland Metropolitan General Hospital in 1962, Dr. Kolobow joined the U.S. Public Health Service, where he bumped into Dr. Robert Bowman. Dr. Bowman was an inventor himself, and he offered Dr. Kolobow a position in the Laboratory of Technical Development at the National Heart Institute (now the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute). There, Dr. Kolobow would continue a life-long quest to perfect the gentle treatment of injured lungs — and branch out to include hearts, too.

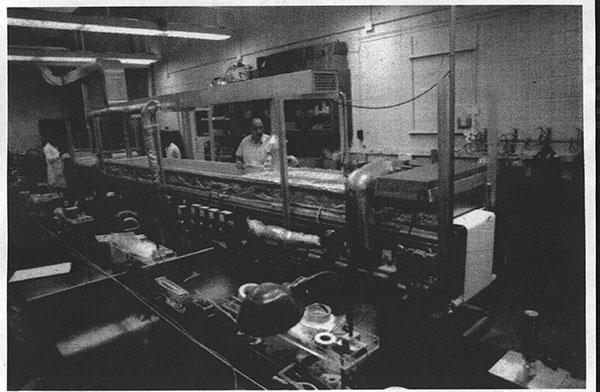

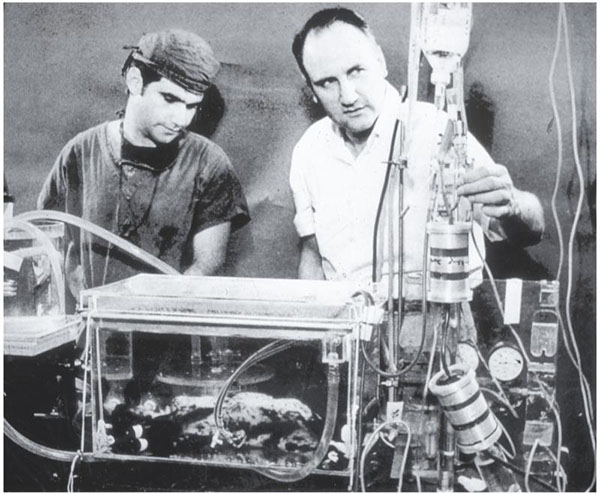

The photo above shows a huge machine that Kolobow constructed in the basement of Building 31 to make ultra-thin membranes without holes. Dr. Kolobow is in the foreground. They had to do the work at night because the smell bothered everyone else in the building.

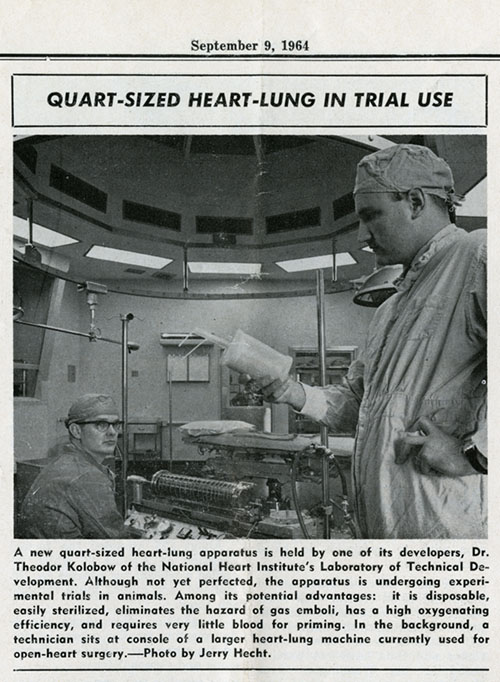

The NIH was a hotbed of experimental heart surgery in the 1960s. Dr. Kolobow contributed by working on how to make operating on the heart easier. The heart-lung machine oxygenated and circulated blood around the heart, enabling surgeons to operate on a stopped heart. But the heart-lung machine was huge and difficult to clean. So, while looking for the best way to oxygenate blood, Kolobow developed the small, disposable heart-lung device described in the above 1964 NIH Record article clipping. While this invention did not replace the heart-lung machine, it did inform Dr. Kolobow’s pioneering work on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) — more on that later.

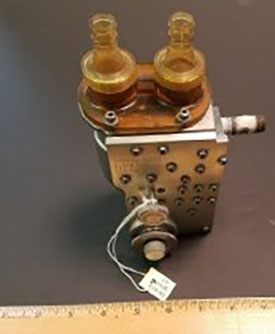

Dr. Kolobow became responsible for more than his own research when he became the chief of the NHLBI's Pulmonary and Cardiac Assist Devices Section in 1970 — he added the duty of contract supervision in the NIH Artificial Heart Program. IRP researchers, universities, and private industry all co-operated to create devices to help diseased hearts. This Army Pulsatile Pump from Dr. Kolobow’s collection was developed by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) and the Harry Diamond Laboratories. It propelled blood through a heart/lung machine with less trauma to the blood than a normal pump and oxygenator; the U.S. Army used it during the Vietnam war.

Being a hands-on person, Dr. Kolobow pursued his own ideas to help diseased hearts. He and Dr. Robert Bowman created a rubber envelope that fit around the heart (pictured above), which then was placed in a rigid Lexan shell so that it couldn’t expand too wide. Suction was used to make the heart 'beat.' The system worked for up to an hour in animal experiments.

Dr. Kolobow and Dr. Bowman also developed this left-ventricle assist device (LVAD), a battery-powered mechanical pump to help when the heart’s left chamber of the heart doesn’t work. This was the more successful design; sometimes the LVAD could be used until a heart transplant donor was found.

Dr. Kolobow was always attempting to find the best way to help patients on ventilators by not harming their lungs or airways, or exposing them to the unnecessary risk of ventilator-acquired pneumonia. With his stream of postdocs, Dr. Kolobow developed cuffed tubes, gilled tubes, mucus slurping tubes, and mucus shaving tubes, along with the ultra-thin walled nitinol tubes. Many of his designs are now in common use; some are still being accepted by the medical community.

Objective: To design and fabricate crush-proof tracheal tubes for newborn infants with the lowest resistance, least dead space, and thinnest wall. The team: An experienced inventor (Dr. Kolobow), his postdocs (Lorenzo Berra and Lorenzo DeMarchi), and Dr. Hany Ali from George Washington University Hospital. The design: flat nickel titanium shape-memory alloy (Nitinol) tubes, one for breathing in and one for breathing out, attached to a Y-connector. The result: Dead air space is decreased so the patient doesn't rebreathe air, and more area allows more air in and out. This work was published in 2004.

Taking over the work of the heart — oxygenating blood — so that people with lung or heart damage can recover was Dr. Kolobow’s long-term goal. In the late 1960s, he and Dr. Warren Zapol developed an artificial placenta, which kept fetal lambs alive. The system required inventing devices that wouldn’t damage blood as it was pumped. Their method was then tested on human infants in acute respiratory distress, showing it was possible to support patients in acute respiratory failure, too. In 1974, they treated an 11-year old boy who was able to participate in athletics at school just four months after recovering from Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Previously, it was thought that the lungs could not recover from ARDS. All of this work helped lead to the extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) used today, in which the machine replaces the function of the heart and lung for long periods of time and with less damage than the heart-lung machine.

“According to his wife, when asked what his greatest achievement had been, he would say, ‘I survived the war.’ If asked what his greatest contribution to medicine was, he would proudly say, ‘ECMO’ (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation).” But those achievements barely scratch the surface of Dr. Kolobow’s career and his quest to take the best care of critically ill patients. We’ve only shared a few examples of his inventions, and we can’t show you the impact that he made on the students going through his lab who have become leaders in medicine around the world — over 50 from Italy alone — or the millions of people that his work has aided. But you can read more about his extraordinary life here.

- The above quote is from “’Treating Lungs’- The Scientific Contributions of Dr. Theodor Kolobow,” John M. Trahanas, Mary Anne Kolobow, Mark A. Hardy, Lorenzo Berra, Warren M. Zapol, and Robert H. Bartlett, ASAIO Journal, 2016 Mar-Apr; 62(2): 203–210.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023