Mining Medical Data to Improve COVID-19 Treatment

Study Reveals Medications Associated With Lower Odds of Severe Infection

By analyzing healthcare data on hundreds of thousands of people, IRP researchers have found clues that certain existing medications might be useful for combating COVID-19.

Many researchers studying COVID-19 have spent the past two years poring over test tubes and isolated cells. However, large troves of data about people’s interactions with the healthcare system can also be a rich source of useful insights. Using one such database, IRP researchers found that older adults taking certain medications were less likely to catch COVID or experience severe repercussions from the virus.1

The vast majority of Americans ages 65 and older are enrolled in the federal government health insurance program known as Medicare. As a result, the U.S. government accrues mountains of health-related information on people in this age group, which is ‘de-identified’ so that it cannot be connected to specific individuals. What’s more, over 80 percent of the people in the U.S. who have died from COVID-19 were 65 or older, making Medicare data particularly useful for researchers who want to understand the factors that influence COVID-related health risks.

Those curious researchers include IRP senior investigator Clement McDonald, M.D., and IRP staff scientist Kin Wah Fung, M.D., who recently mined Medicare data to see whether older adults taking certain medications were more or less likely to be diagnosed with COVID, be hospitalized with the virus, or die from it. The dataset they analyzed included information on more than 374,000 older adults who received a COVID-19 diagnosis between April 1 and December 31, 2020, including which medications each person was taking during that period and when they were prescribed those drugs.

“COVID doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” says Dr. Fung, the new study’s first author. “Particularly in elderly patients, they may suffer from a host of chronic conditions and they may be taking various drugs because of those conditions. Either those conditions themselves or the drugs they’re taking may affect the susceptibility of a patient to COVID.”

Rather than give a drug to volunteers to determine its effects, as would be done in a clinical trial, the IRP study took advantage of the fact that many older adults already take certain medications on a regular basis.

Nearly three-quarters of the people included in the data who were diagnosed with COVID-19 during that timespan were taking at least one of the drugs Dr. Fung and Dr. McDonald were interested in. They specifically focused on medications that either influence biological pathways that are also affected by the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 or had been previously studied for their effects on the illness.

“In some of the prior studies, the findings conflicted with each other, so there was no definitive conclusion as to whether these drugs were beneficial or harmful,” Dr. Fung says. “Also, because we have a huge dataset, the number of patients in our study is at least several times more than in most of the published studies.”

“The special strength of the Medicare database, as opposed to some of the commercial healthcare databases and others, is you’ve got practically everybody,” adds Dr. McDonald, the study’s senior author.

After analyzing the Medicare data with the help of IRP biostatistician Seo Hyon Baik, Ph.D., the researchers found that several types of drugs were associated with lower odds of being diagnosed with COVID-19 or experiencing a severe infection. These promising drugs included statins taken to reduce blood cholesterol levels; medications like warfarin that reduce the risk of blood clots to help prevent heart attacks and strokes; and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blocks (ARBs), which treat high blood pressure by reducing the effects of a chemical in the body called angiotensin II. The finding about ACE inhibitors and ARBs was particularly intriguing because, early in the pandemic, it was thought that those drugs might worsen COVID-19 infection by increasing the abundance of the ACE2 receptor, which angiotensin II binds to in order to exert its effects on blood vessels.

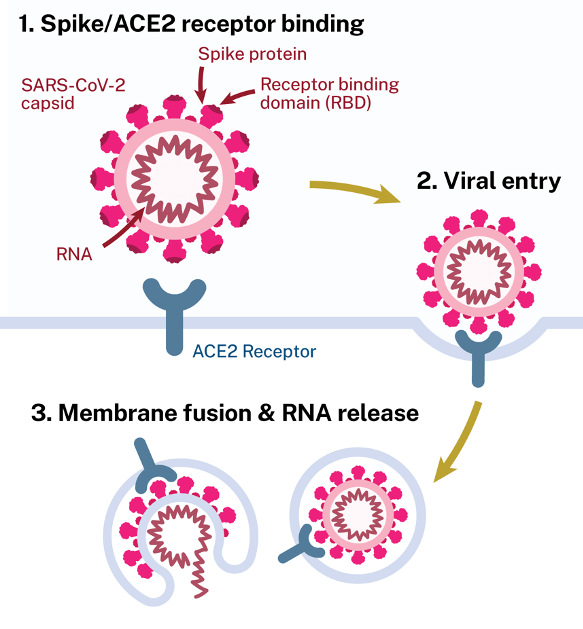

This diagram shows how the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19 uses the ACE2 receptor to infect cells.

“The ACE2 receptor is a doorway through which COVID enters the cell,” Dr. McDonald explains. “There was some thought that if you had more of it, then more virus could get into cells, but that wasn’t the way it turned out.”

“Because of all the complex interactions between the drugs, the virus, and the cell, it’s very difficult to know what exactly will happen in a patient,” adds Dr. Fung. “Until you have a big study like ours or you have a really well-designed clinical trial, it’s really difficult to answer what the net outcome will be when you tinker with the angiotensin pathway. That’s how science is: often there are multiple pathways and there are many possible ways that the effects of a drug or virus can change the pathway, so you go back to the roots — you document the outcomes and that is the ground truth that will show whether your hypothesis is actually true or not.”

The IRP researchers also looked at the effects of hydroxychloroquine, which has long been used to treat malaria, rheumatoid arthritis, and chronic autoimmune conditions. Using hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 has been controversial ever since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration authorized it for that purpose on an emergency basis in March 2020 and then revoked that authorization three months later. At first glance, the IRP study suggested that hydroxychloroquine actually increased the odds of being diagnosed with COVID-19 by more than 60 percent, but when the IRP team adjusted its analysis to exclude people who only began taking the drug in 2020 — possibly because they thought it would help ward off COVID-19 rather than due to medical need — it turned out that hydroxychloroquine had no effects on COVID-19 diagnosis, hospitalization, or death.

“We know now that hydroxychloroquine does not protect you, but if these people had a false sense of security because they thought they were taking a drug that would protect them from COVID, they might have been less likely to practice measures like masking, and so they may have been more likely to catch COVID,” Dr. Fung says. “If you’re not careful in designing your study, you can come to false conclusions like hydroxychloroquine being associated with increased risk of catching COVID.”

The study was led by Dr. Kin Wah Fung (left) and Dr. Clement McDonald (right).

Ultimately, the information gained from the study and similar endeavors will provide important leads for researchers looking to leverage existing medications as potential COVID-19 treatments. In addition, such studies demonstrate the value of the federal government’s efforts to collect a wide variety of anonymized medical information about American citizens.

“We are more and more talking about a ‘learning’ healthcare system,” Dr. Fung says. “Even during routine healthcare, we collect data, and that data can actually feed back into knowledge discovery and hypothesis generation. This is one mechanism through which the huge enclave of Medicare claims data can be used in research. It’s a very powerful and useful dataset.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Fung KW, Baik SH, Baye F, Zheng Z, Huser V, McDonald CJ. Effect of common maintenance drugs on the risk and severity of COVID-19 in elderly patients. PLoS One. 2022 Apr 18;17(4):e0266922. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0266922.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023