Genetic Sequencing Solves Drug Reaction Mystery

Immune System Genes Linked to Severe Side Effects in Patients with Rare Disease

IRP researchers helped identify a set of genes that places some patients at risk for dangerous reactions to particular medications that alleviate disease by suppressing the immune system.

When you run the largest-ever study of a rare childhood disease, you become the go-to person when your peers notice something peculiar in patients with the illness. It was not too surprising, then, when a researcher from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, asked IRP investigator Michael Ombrello, M.D., to help her team follow a new lead in the mystery of why some patients with a rare inflammatory condition called Still’s disease were coming down with a life-threatening lung ailment. The results of their collaboration could lead to a new precision medicine approach that individualizes therapy for Still’s disease based on patients’ DNA.1

Still’s disease, which is known as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) when it develops in children and adult-onset Still’s disease in adults, causes a potentially life-threatening hyper-activation of the immune system that leads to frequent fevers and inflammation in tissues throughout the body. This inflammation also causes arthritis, a degradation of the joints.

In 2016, Dr. Ombrello partnered with colleagues at NIH and around the world to launch the International Childhood Arthritis Genetics (INCHARGE) Consortium, which they used to perform the first and, to-date, largest genomic study of children with Still’s disease/SJIA.2 The study, which includes nearly a thousand patients, used genetic data that ended up coming in handy for figuring out why some Still’s patients inexplicably had begun developing severe damage to their lungs.

“This type of lung disease hadn’t been seen before even though we’ve known about Still’s disease for more than a hundred years,” Dr. Ombrello says. “A couple papers were published that described this lung disease, but nobody really knew what was going on.”

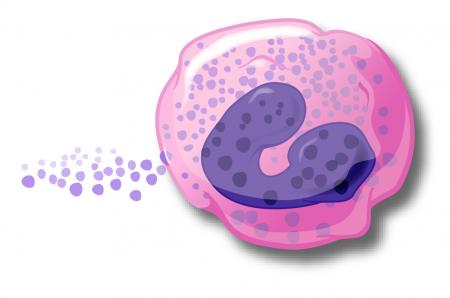

Cartoon illustration of an eosinophil. High levels of these infection-fighting white blood cells in Still’s patients with an unexplained lung disease provided a clue that the lung ailment was caused by a reaction to their medication.

Eventually, researchers found that Still’s patients with this lung damage had high numbers of infection-fighting white blood cells called eosinophils, which can indicate an immune system reaction to an allergen or medication. The culprit, it turned out, was a set of drugs that alleviate Still’s disease symptoms by inhibiting inflammation-promoting immune system molecules called interleukin-1 and interleukin-6. Once patients with the lung ailment were taken off these drugs, their condition improved. However, the medications are so effective at relieving the symptoms of Still’s disease that entirely stopping their use would be a major setback for treating the illness. As a result, researchers like Dr. Ombrello and his Stanford collaborators have been searching for a way to identify ahead of time which Still’s patients might experience this dangerous reaction to the medications.

In their study, Dr. Ombrello’s team and the Stanford researchers accomplished exactly that. They specifically looked at genes that produce human leukocyte antigen (HLA) markers, which the immune system uses to distinguish the body’s own cells from harmful invaders like bacteria and parasites. By comparing HLA genes in Still’s patients who had the dangerous medication-linked reaction to those of 550 Still’s patients of similar ancestry involved in the INCHARGE study, they discovered that a particular set of HLA genes usually inherited together, called a haplotype, was much more common in the patients who experienced the drug reaction compared to Still’s disease patients in general.

The researchers then compared the HLA genes of Still’s patients who experienced the drug reaction to those of patients who had received the same medications without developing the drug reaction. Among Still’s patients who identified as white, 30 out of 36 who had experienced the drug reaction had a particular HLA gene variant that is part of the risk-related haplotype, while none who tolerated the drugs well did. Similarly, 21 of 28 non-white Still’s patients who had the medication reaction had an HLA variant associated with the haplotype, compared with only 2 of 11 who did not react to the medications.

Sequencing the HLA genes of Still’s disease patients could help prevent the potentially life-threatening lung condition that had long baffled researchers. Further research will determine whether such screening is warranted for patients with other diseases that are treated with the same medications.

“In a certain way, this paper has opened Pandora’s box,” Dr. Ombrello says. “We need to keep our eyes open because Still’s patients who have this risk haplotype and get treated with these drugs have a higher risk of having this drug reaction and developing this lung disease. People who are already on these medications, if they’re found to have this risk haplotype in the presence of symptoms indicative of a drug reaction, I think that they should seriously consider discontinuing those medications. For patients who are receiving these medications who are stable and whose disease is under good control, that creates a dilemma because we know this risk exists, but at the same time they continue to be treated in a way that so far has been working well.”

“It’s an explanation of a problem, but at the same time it’s a recognition of another problem that comes with a lot of additional questions,” he continues. “It complicates matters for a subset of people who are on what are considered the best medications for this illness.”

The study also found evidence suggesting that dangerous reactions to the same medications might be a problem for other patient populations. The study looked at 19 children with Kawasaki disease, an inflammatory disease affecting blood vessels throughout the body. Three of the four patients who had delayed, adverse reactions to one of the medications had a particular HLA gene variant often found as part of the haplotype linked to the drug reactions in Still’s patients. None of the 15 Kawasaki’s disease patients who tolerated their medications well had that HLA variant.

“It does suggest there could be a link that extends beyond Still’s disease alone,” Dr. Ombrello says. “However, I think we have to be cautious about stating the conditions under which this risk is present. We don’t know right now, so it’s prudent to take our findings into consideration generally, but we can’t be alarmist either because these HLA variants are present in 20 to 25 percent of the European population.”

Dr. Michael Ombrello, the new study’s co-lead author

Though more research on the topic is sorely needed, Dr. Ombrello thinks the results of the new study warrant preemptively sequencing the HLA genes of all Still’s disease patients who might be prescribed one of the medications responsible for the drug reaction. Moving forward, scientists will need to figure out for sure whether patients with conditions other than Still’s disease are having dangerous reactions to the same medications. Dr. Ombrello also hopes to further narrow down the specific variants in HLA genes that place patients at risk for the drug reaction.

“It’s really hard, since these genes are linked together evolutionarily, to figure out which piece of the haplotype is the one that’s truly causing the drug reaction versus if there’s multiple different genes on the same haplotype that are contributing synergistically,” Dr. Ombrello says. “I think there’s going to be a shared genomic profile of people who have this reaction, so I’m trying to enroll every patient I can with Still’s disease who is developing hypersensitivity to these treatments.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Severe delayed hypersensitivity reactions to IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors link to common HLA-DRB1*15 alleles. Saper VE, Ombrello MJ, Tremoulet AH, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Nov 17;annrheumdis-2021-220578. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220578.

[2] Genetic architecture distinguishes systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis from other forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: clinical and therapeutic implications. Ombrello MJ, Arthur VL, Remmers EF, et al. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017 May;76(5): 906–913. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210324.

Related Blog Posts

- IRP’s Luigi Notarangelo Elected to National Academy of Medicine

- Rare Disease Research Reveals Why Immune Cells Go Wild

- Unlocking the Genetic Mysteries of Rare Autoinflammatory Diseases

- Friendly Virus Could Deliver Gene Therapy Under Immune System’s Radar

- Rare Genetic Variants Underlie Susceptibility to Reproductive Disruption

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 23, 2023