Smartphone Apps Show Promise for Assessing Multiple Sclerosis Symptoms

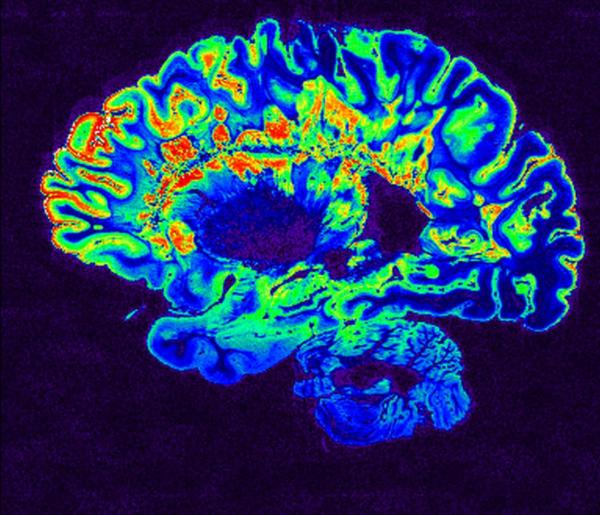

This MRI scan shows the brain of a patient with multiple sclerosis (MS). A new IRP study suggests that smartphone apps might provide an easier, cheaper, and faster way to measure MS symptoms.

The three-quarters of Americans who own a smartphone use them not just for communicating but also keeping a calendar, playing games, scouring the Internet for funny cat memes, and — soon — maybe even evaluating their neurological health. A new study conducted by IRP and University of Maryland researchers has confirmed the potential of smartphone apps for gauging symptoms of the neurological disease multiple sclerosis.1

Multiple sclerosis, or MS, is caused by the loss of the fatty coating that helps neurons transmit electrical signals. The disease, for which there is no cure and limited treatment, can cause a wide array of symptoms, including numbness, motor weakness, coordination difficulties, and vision loss.

According to IRP investigator Bibiana Bielekova, M.D., the new study’s senior author, the assessments commonly used in clinical trials for MS therapies are not very sensitive. In fact, she says, in a trial that tracks the progression of MS symptoms for just one or two years, those measures might only detect worsening symptoms in around 10 percent of patients. This makes it extremely difficult to determine the effectiveness of a new medication without running extremely long or large studies.

“It’s unsustainable — these clinical trials are very expensive and we are running out of patients” says Dr. Bielekova. “We need to be able to measure disability progression in the smallest possible number of patients in the shortest possible time frame because that way we can screen drugs much more efficiently.”

Dr. Bielekova’s IRP team focuses on remedying this problem by creating easier and more sensitive neurological assessments. For example, her group has created an iPad program called NEUREX2 that allows time-crunched doctors to quickly determine a patient’s scores on several measures of MS-related disability.

Dr. Bielekova’s new study was born out of an attempt to further decrease the time and effort needed to gauge MS symptoms. She teamed up with Atif Memon, Ph.D., a professor at the University of Maryland, College Park, who was teaching a class on app development for the Android operating system used on many smartphones. With guidance from Dr. Bielekova and her IRP colleagues, Dr. Memon’s students developed a range of smartphone apps that could assess patients’ motor and cognitive abilities in similar ways to traditional tests like the 9-Hole Peg Test (9HPT), which measures the time it takes a patient to place nine pegs in nine holes and then remove them.

“You don’t need to have nurses administering these tests in the clinic,” Dr. Bielekova explains. “You can simply have patients doing them with their phones.”

After further polishing the students’ programs, Dr. Bielekova’s group put two of them to the test: a finger-tapping app that had participants simply tap the screen as many times as possible in ten seconds and a balloon-popping app in which players used their fingers to pop balloons that appeared in randomly generated locations on the screen. These tests differentiated MS patients from healthy volunteers nearly as well as the 9HPT and were easier to do, as four patients were unable to complete the 9HPT but all patients could do the app-based assessments. In addition, each patient’s scores on the app-based tests were similar to their performance on the 9HPT. Moreover, compared to performance on the 9HPT, scores on the app-based tests more closely corresponded to scores on neurological exams done using the NEUREX software, suggesting that the smartphone apps were not just easier and faster gauges of MS symptoms than an in-person test done in a hospital setting but they might also provide a better means of assessing symptoms than traditional functional assessments.

The app-based tests also had the added benefit of allowing the researchers to collect other types of data related to patients’ symptoms. For example, since the finger-tapping test required only motor skills while the balloon-popping test required motor, visual, and cognitive abilities, comparing scores on the two tests allowed the researchers to more specifically measure visual and cognitive impairments. Similarly, the amount of time that patients’ fingers remained in contact with the screen during the finger-tapping test showed promise as a means of identifying patients with coordination problems caused by damage to a part of the brain called the cerebellum.

Dr. Bielekova’s team is currently finalizing a study of six other apps that originated in Dr. Memon’s class. After additional refinement, she aims to combine her team’s NEUREX iPad software with the smartphone apps to create an improved assessment for evaluating MS patients.

“Obviously these apps will not replace doctors, but I really believe that they can fill an important gap,” Dr. Bielekova says. “They will provide reliable data to the clinicians about how the patient is doing, and they will also empower patients by providing them with feedback about whether their disease is progressing.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Identifying and Quantifying Neurological Disability via Smartphone. Boukhvalova AK, Kowalczyk E, Harris T, Kosa P, Wichman A, Sandford MA, Memon A, Bielekova B. Front Neurol. 2018 Sep 4;9:740. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00740. eCollection 2018.

[2] NeurEx: digitalized neurological examination offers a novel high‐resolution disability scale. Kosa P, Barbour C, Wichman A, Sandford M, Greenwood M, Bielekova B. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018 Oct; 5(10): 1241–1249.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, January 30, 2024