Early Women Scientists of NIH, Part 2

Jane Stafford, “The First Lady of Science Writing,” began writing about health and science for magazines in 1926, winning several awards. She came to interpret information from the scientific community for the press and public at the National Institutes of Health in 1956, and was Assistant or Acting Director of the Office of Information 1966-1971.

Stafford taught other science writers at seminars, such as one in 1965 on the terms and concepts of genetics, a relatively new science then. She also wrote reports for Congress, edited conference proceedings, and was president of the Women’s National Press Club. Find out what she received on her retirement (page 3).

Like many in the second wave of women scientists at the National Institutes of Health, Dr. Margaret Kelly began as a technician and got her PhD while she was working. She began in 1940 as a medical technician in the National Cancer Institutes (NCI)’s Laboratory of Pathology and was a senior investigator in the Laboratory of Chemical Pharmacology at her death in 1968.

Kelly focused on what caused cancer and what drugs could be used to fight it, establishing a monkey colony which resulted in her being able to grow tumors in tissue culture and looking at about 3000 chemicals to find a few that might work as cancer treatments. Read more about her research on page 8.

“My move in 1943 to the National Institute of Health was intended to be for the duration of the war, but as you can see, I’m still here 34 years and 1 month later,” said Dr. Willie W. Smith, on her retirement. Smith witnessed an atomic bomb test in the early 1950s as part of her career-long studies on how factors like altitude, temperature, hypoxia, exercise, hormones, antibiotic use, and diet affect recovery from radiation poisoning.

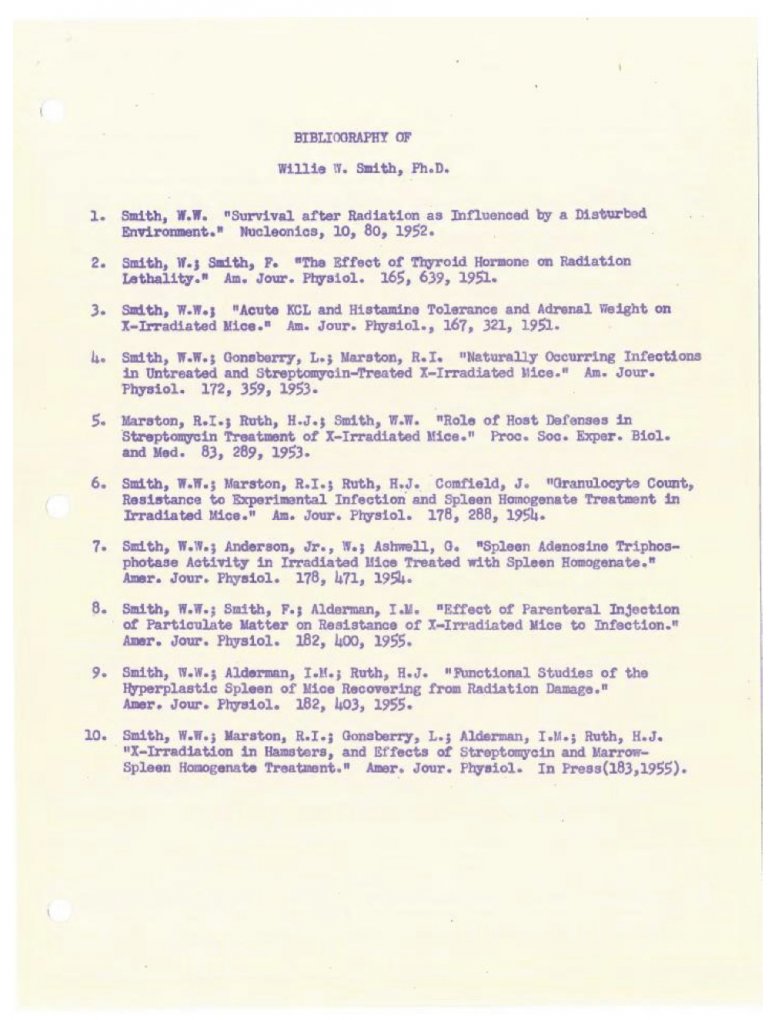

We have no photo of Dr. Smith; this bibliography below is from an August 1955 special report on NCI. Smith also guided Robert Marston, who later became an NIH director, in his experimental work as a graduate student. Smith worked in intramural programs at both the NCI and the National Institute of Arthrities and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS). She received her PhD from Columbia in 1938. Read more on page 7.

The first woman scientist at the National Institute of Dental Research (as NIDCR was called in 1947) was fascinated by the question, “Why do some people have teeth full of cavities while others do not? Is it a pattern they inherit or an environmental factor?”

Dr. Rachel Harris Larson, had accompanied her younger sister to the “big city” and got a job at the institute as a technician. She earned her PhD from Georgetown at night. Dr. Larson retired as chief of the Preventive Methods Development Section in the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) in 1977. Read more about the Harris sisters on page 2.

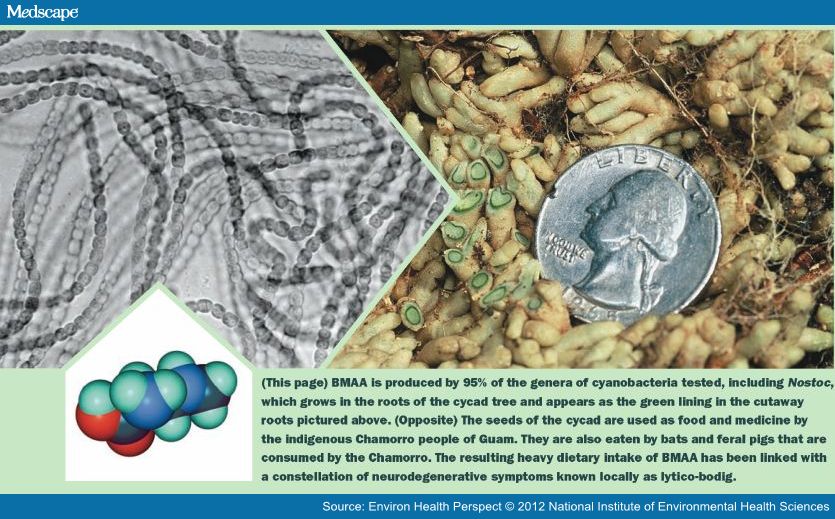

This illustration from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) is about a disease caused by eating cycads, a sort of tree fern. Dr. Marjorie Grant Whiting, a commissioned officer and nutritional anthropologist in the U.S. Public Health Service detailed to the National Institutes of Health, recognized the similarity between a progressive paralysis of the legs and neurodegenerative diseases in Guam in 1963.

Dr. Whiting asked Arthur Bell, of the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, to test cycad seeds. Thus began research into cycads, diet, and disease. Whiting established a foundation that created the Endowment for Indigenous Knowledge Advancement at Penn State, which still finances student researchers.

To learn more about other early women scientists of NIH, visit Part 1 in this blog series.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023