From the Annals of NIH History

NIH Families Had to Fight for Their Right to Vote

Case Worked Its Way Up to the Supreme Court

When 20-year-old Edward Tabor tried to register to vote at the Montgomery County, Maryland, Board of Elections office in February 1968, he saw his application, and his parents’ voter cards, destroyed in front of him. The subsequent protest by the Tabor family and their neighbors eventually reached all the way to the United States Supreme Court. At stake—for certain NIH staff and for others across the country—was nothing less than the exercise of the Constitutional right to vote.

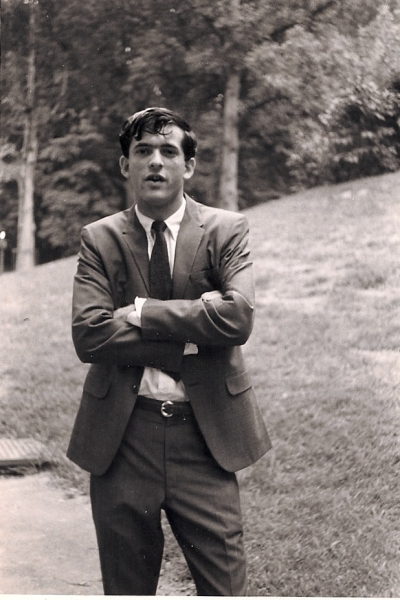

CREDIT: EDWARD TABOR

Edward Tabor on the NIH grounds in 1969. When he tried to register to vote at the Montgomery County, Maryland, Board of Elections office in February 1968, he saw his application, and his parents’ voter cards, destroyed in front of him.

The issue was that Tabor and his parents who both worked in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)—Herbert Tabor (1943-2020) and Celia Tabor (1952-2005)—lived on the NIH campus in one of the 15 brick houses located in the northeast corner. In 1963 the Maryland Court of Appeals had ruled, in a case outside NIH, that individuals living on federal government property didn’t meet Maryland residency requirements for voting. The application of the ruling to NIH in 1968 by the Board of Elections effectively disenfranchised not only the Tabors and their neighbors but also other NIH scientists and employees who lived in the apartment building (Building 20, since demolished) on campus.

Shortly after Ed Tabor’s abortive attempt to register, his parents and other campus residents received notices from the Board of Elections that they had been removed from the voter rolls. Apartment resident Tillye Cornman (see sidebar) sought legal representation for the NIH residents and obtained pro bono representation by Montgomery County Democratic Chairman and political activist Richard Schifter. Schifter quickly obtained an injunction allowing previously registered campus residents to vote in the 1968 presidential election.

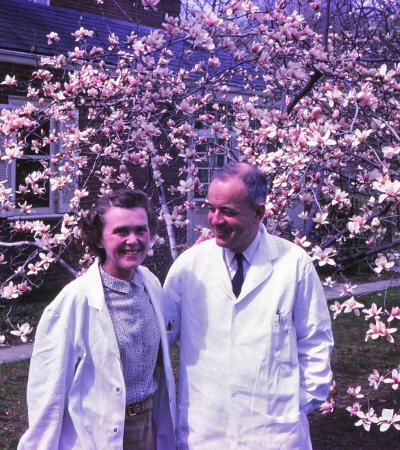

CREDIT: EDWARD TABOR

Celia and Herbert Tabor standing next to their family house on the northeast corner of the NIH grounds in 1967. In 1963 the Maryland Court of Appeals had ruled, in a case outside NIH, that individuals living on federal government property didn’t meet Maryland residency requirements for voting.

“That basically allowed everyone to vote that year except me,” said Ed Tabor, now a retired physician-scientist in National Cancer Institute (1988-1995) living in Bethesda. Another campus resident had also been barred from registering shortly after Tabor’s interaction with the Board of Elections but left NIH shortly thereafter. A second court order permitted Tabor to vote in a 1969 special election.

The Federal District Court restored voting rights to the NIH plaintiffs, but the Maryland Attorney General appealed that decision to the United States Supreme Court. Twelve individual plaintiffs, including Ed Tabor, were represented.

Assistant Attorney General Robert Sweeney, arguing for the state, expressed sympathy for the residents but stated, “In a government of laws and not of men…this question should not and cannot be decided out of sympathy for the Appellee’s position.” Schifter, meanwhile, argued that denying NIH residents the right to vote violated the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

The Supreme Court justices agreed, with one referring to the state’s arguments as “much ado about nothing,” and in a unanimous decision handed down in June 1970 [Evans v. Cornman, 398 U.S.419(1970)] permanently restored the residents’ voting rights. Ed Tabor was able to register and vote in the 1970 midterms and 1972 presidential election—although by that time he was away at medical school at Columbia University (New York) and voted absentee.

It’s unclear why the Board of Elections suddenly started to enforce the 1963 law disenfranchising residents of federal enclaves five years after the Appeals Court decision. According to Ed Tabor, attorney Schifter had a theory. “He told me that more United States government employees were Democrats than Republicans at that time,” said Tabor. “And [Schifter believed that] “the actions of the voter registration office seemed to be calculated to decrease the number of registered Democrats.”

Tabor remembers that the elections workers immediately recognized his fairly obscure address as being on the NIH campus. “Clearly they were waiting for someone from NIH to attempt to register,” he said. Notably, Schifter did not assert this theory in his oral argument before the Supreme Court, and the number of previously registered Democrats involved in the lawsuit only slightly exceeded the number of previously registered Republicans (6 versus 4).

Since 1970, Evans v. Cornman has been cited in several other Supreme Court cases involving voting rights, including an unsuccessful case supporting Washington, D.C., statehood. And it made a big impression on Ed Tabor. “I was very serious about voting in every election for many years after that,” he said.

Tillye Cornman, M.D.: A Remarkable Life

Tillye Cornman, who spearheaded the legal effort to restore voting rights to NIH campus residents, was born in New Orleans in 1916, the oldest of eight children. A graduate of Louisiana State University’s medical school (New Orleans), Cornman was practicing neurology and psychiatry when she was shot outside her office by a patient undergoing treatment for mental illness. She used a wheelchair for the rest of her life due to the resulting spinal cord injury.

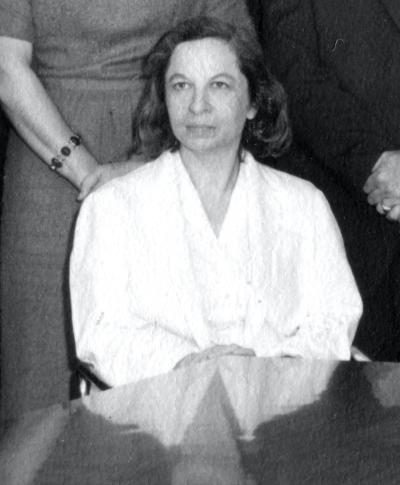

CREDIT: OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

Tillye Cornman at the NIH Clinal Center in 1961. Cornman served as head of the NIH Clinical Center Rehabilitation Medicine Department and spearheaded the legal effort to restore voting rights to NIH campus residents

Her rehabilitation sparked a lifelong interest in the field, and after retraining as a physiatrist, she became head of the NIH Clinical Center Rehabilitation Medicine Department in 1954. Colleagues remember her as an unwavering advocate for her patients and a dedicated member of the staff. In 1955, she told the NIH Record that “The concept of rehabilitation is really teamwork” and was quick to acknowledge the contributions of other members of her team.

She retired in 1988 but served as a consultant for the Clinical Center after that. For most of her career, she lived in a first-floor flat in the apartment building on the NIH campus, where she raised her daughter as a single mother while working full time.

CREDIT: DAVID SAMUEL

In the 1960s, Tillye Cornman’s complaint to then-United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy resulted in the construction of a ramp outside the National Archives building (pictured) so it was wheelchair-accessible.

Family and colleagues remember Cornman as a powerful advocate not only for her patients but also for the causes she championed. For example, her complaint to then-United States Attorney General Robert Kennedy resulted in the construction of a ramp outside the National Archives building after she was unable to traverse the front stairs in her wheelchair.

Cornman died in Gaithersburg, Maryland, aged 82, in 1999. She was survived by a daughter, two grandchildren, a great-grandchild, and hundreds of patients whose lives she touched during her four decades of service.

Kate Nagy is Deputy Director of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) Office of Planning, Analysis, and Evaluation, where she coordinates strategic planning and reporting efforts. Prior to NIA, she spent nine years in strategic planning, evaluation, and scientific communications at the National Cancer Institute. A graduate of the Universities of Kansas and Vermont, Nagy has a master’s degree in English as well as a certificate in legislative studies from the Government Affairs Institute at Georgetown University (Washington, D.C.).

This page was last updated on Monday, January 9, 2023