St. Elizabeths Hospital

How Its Architecture Informs Us of the Past and Present

Once referred to (unofficially) as the “U.S. Lunatic Asylum,” St. Elizabeths Hospital in Southeast Washington, D.C., established in 1855, remains open, welcoming and helping patients with serious and persistent mental illnesses. Most people, however, are unaware of the numerous changes the hospital has undergone both in landscape and in medical practice.

In her recent presentation at NIH, historian Sarah Leavitt laid out the evolution of St. Elizabeths Hospital, an institution for people with mental illness, established in 1855.

Sarah Leavitt, who is a former historian in the Office of NIH History (2002–2006) and an expert on the hospital’s architectural story, gave a talk on June 24, 2021, as part of the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum’s biomedical history lecture series. She previously worked at the National Building Museum (Washington, D.C.) where she curated its St. Elizabeths Hospital exhibit in 2017. She held curator positions at various institutions before working at NIH and is now a curator and historian at the Capital Jewish Museum (Washington, D.C.).

Leavitt’s interest in the history of medical institutions began when she was an undergraduate at Wesleyan University (Middletown, Connecticut) with an honors thesis on the Connecticut Industrial School for Girls (Middletown, Connecticut), an institution for “vagrant” or delinquent girls. “This [thesis] started my thinking about institutionalization and what was the right approach,” said Leavitt, who went on to get a Ph.D. in American Studies and Civilization at Brown University (Providence, Rhode Island).

By happenstance, she briefly visited St. Elizabeths during her time at NIH, but it wasn’t until she joined the National Building Museum that she had an opportunity to view the vast collection of the St. Elizabeths architectural drawings held at the Library of Congress (Washington, D.C.). From there, the story of St. Elizabeths grew and resulted in an exhibit that not only included 20 of the original architectural drawings but various historical elements such as a writing desk on which the first piece of legislation toward the establishment of St. Elizabeths Hospital was written, to the ventilation grills that once graced its inner walls.

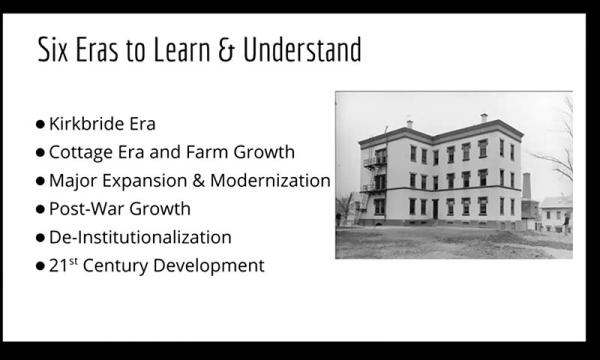

Leavitt posed two main questions to ponder: First, what is the connection between the built environment and treatment for mental illness and how has this changed over time? And second, why was St. Elizabeths built where it was and how will the land be used in the future? To answer these, she took us through a journey through time.

First opened by the federal government in 1855, the conception of St. Elizabeths Hospital was largely pioneered by Dorothea Dix, an early 19th-century activist who advocated improving conditions for the mentally ill. Dix partnered with the hospital’s first superintendent, Dr. Charles Nichols, to choose a location and design based on the views of Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, who championed the philosophy of “moral treatment” based on compassion and respect. He believed that architectural landscape and view could “cure” a patient who had mental illness.

The hospital would eventually spread into a 350-acre campus in Southeast Washington, D.C., and its first building—the Center Building—was constructed in the style of the “Kirkbride Plan.” It had a characteristic “V” shape in which the central core housed administrative staff and the wings accommodated patients in individual rooms that brought in ventilation and sunlight. Patients were organized based on their symptoms and severity with those suffering from severe symptoms being furthest from the center. Several other hospitals featuring the iconic “V” design were built across the United States between 1848 and 1913, with some 33 buildings—no longer used as hospitals—retaining their original form today.

COURTESY OF SARAH LEAVITT

Sarah Leavitt, a former historian at NIH and now a curator and historian at the Capital Jewish Museum, gave a talk recently about St. Elizabeths Hospital, an institution for people with mental illness.

Although the importance of surroundings was recognized, the “view was often marred by construction,” Leavitt noted. “The ideology of this rural and bucolic setting was really punctured…and didn’t always have that idealistic quiet.”

Segregation of white and Black patients occurred during St. Elizabeths’ first 100 years. Leavitt, however, highlighted the differences between architecture: White patients had accommodations, based on the Kirkbride Plan, that were elaborate and decorative—even the ventilation grates had intricate patterns. In contrast, Black patients lived in less decorative lodges that were not based on the Kirkbride Plan and they slept in dormitory-style rooms.

It soon became apparent that environment alone couldn’t cure many mental illnesses and that the Kirkbride vision was insufficient in dealing with the increasing demand for mental-health facilities. The architectural landscape evolved into a cottage and farm-style system in the 1880s. This change reflected the belief that patients could be better cared for in smaller, more homelike buildings that specialized in certain mental illnesses. Self-sufficiency also became an important aspect, with participation in farming activities soon becoming part of white patients’ therapy programs.

Medical research soon became important at St. Elizabeths. During the early 20th century, the Blackburn Laboratory, named for neuropathologist Dr. Isaac W. Blackburn (1851–1911), was established. Scientists there made major contributions to neurological research, with particular focus on the study of brains of patients with mental illness. There is “an extraordinary record of autopsies performed at the hospital and descriptors of various diseases of the brain,” said Leavitt. A bittersweet detail: Chairs were located in the autopsy room to allow for observers; these chairs are now used for visitors in the St. Elizabeths Hospital waiting room.

By the 1950s, the initial hope that provision of moral treatment could help rehabilitate patients had given way to the ever-persisting mindset of needing to have people with mental illness walled away from the general public. An increasing number of patients contributed to overcrowding, with St. Elizabeths population going from 2,000 patients at the beginning of the 1900s and reaching as many as 8,000 patients in the early 1960s. Needed expansion, coupled with decreasing funds, eventually culminated in the creation of utilitarian structures that were seen as “warehouses for the mentally ill,” said Leavitt. These buildings were boxlike and devoid of the intricacies seen in earlier architecture, becoming what many may consider as the quintessential institutional aesthetic.

From 1967 to 1987, the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) had administrative control over the hospital. During this time, the rise of the patient rights’ movement, combined with increased medical research and federal reluctance to provide more funding encouraged the ensuing de-institutionalization of St. Elizabeths. Beginning in the 1960s with President John F. Kennedy’s proposal to end custodial care and open 1,500 community mental-health clinics, Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter aimed to fund this network of clinics; however, the passing of President Ronald Reagan’s Omnibus Bill of 1981 led to severe restriction of federal funding for mental-health care. During this 20-year period, St. Elizabeths experienced an exodus of patients, and by the late 1970s the population had decreased to nearly 2,000 patients.

What remains of St. Elizabeths today? Once comprising two campuses (West Campus and East Campus), the hospital facilities were consolidated to a portion of the East Campus and is now operated by the District of Columbia Department of Behavioral Health, which took over administrative control in 1987. (NIMH continued to run a research program there until 1999, when the NIMH Neuroscience Center/Neuropsychiatric Research Hospital was transferred to the NIH Bethesda, Maryland, campus.) The city has redeveloped the rest of the East Campus into residential and entertainment spaces. Several buildings still remain, including the Center Building located on the West Campus, which has been extensively rebuilt and is now home to the Department of Homeland Security headquarters.

Leavitt closed with not only a poignant reminder of society’s responsibility toward supporting and funding mental-health programs, but also several lingering questions, such as what were 19th-century moral reformers trying to accomplish by institutionalizing mental patients or why did the reformers do things as they did? More importantly, what should we do now? Leavitt left her audience with one final question to consider: “How can we use architecture and landscape moving forward to promote wellness?”

To view a videocast of Sarah Levitt’s lecture “Architecture and Mental Health Treatment: A Look Back at St. Elizabeths in Washington, D.C.,” go to https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=42142.

Leanne Low is a visiting postdoctoral fellow in the Laboratory of Malaria and Vector Research in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, where she is investigating the role of a Plasmodium falciparum protein in the intracellular development of the malaria parasite. Outside of work, she enjoys trying new foods, exploring new places, and hanging out with her fiancé and their cat Monty and dog Senne.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, February 1, 2022