From the Annals of NIH History

Stories About Marshall Nirenberg Before He Became the Man the World Knew

CREDIT: TARA MOWERY

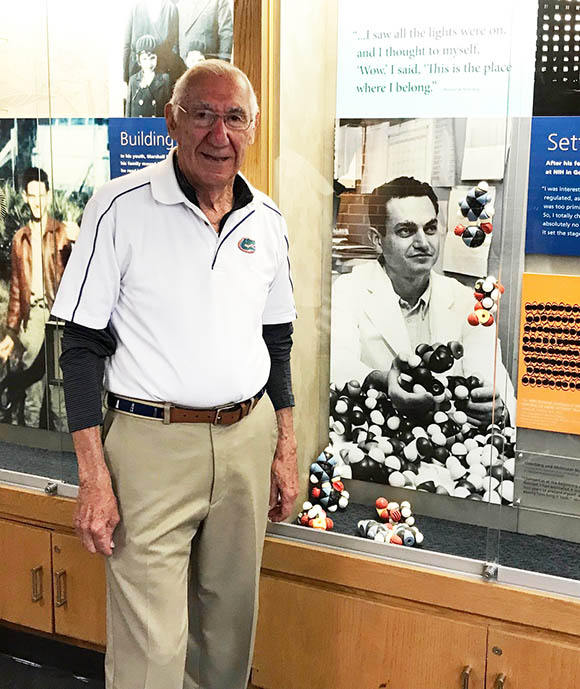

Reunited: David Aronson, an old college friend of Marshall Nirenberg's pauses to admire the Nirenberg exhibit in Building 10 when he was visiting NIH.

You would never believe how much meaning there can be behind catching a fly. For as long as I can remember I have had memories of my grandfather “Papa,” David Aronson, catching flies with his bare hands, right out of the air, without ever harming the fly. My Papa worked with various animals throughout his 50+ years as a veterinarian in Pensacola, Florida, but he learned this trick from an unlikely source.

Papa went to the University of Florida (Gainesville, Florida) from 1948 to 1952, where he learned to catch flies with his roommate who was, at the time, studying caddisflies for his master’s thesis in zoology. Who was this roommate? It was none other than Marshall Nirenberg (1927–2010), who later became an NIH scientist and a recipient of the 1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

CREDIT: DAVID ARONSON

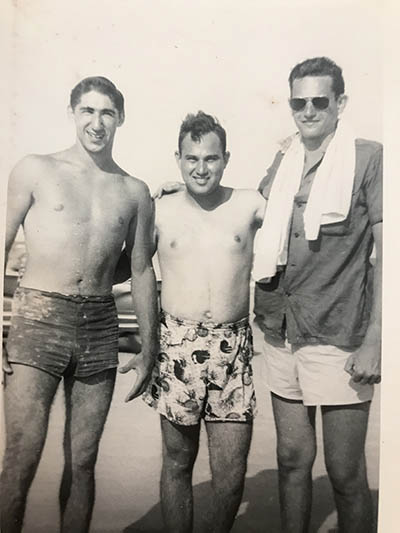

In his college days, Marshall Nirenberg (right) enjoyed going to the beach with David Aronson (left) and other friends.

Marshall and my Papa met in 1948 and became roommates and fraternity brothers in Pi Lambda Phi in 1950 at the University of Florida. They were the only ones who stayed at the frat house during the summer so they “borrowed furniture” from the house to furnish an apartment and rented out rooms to pay for their tuition and fun money. They immediately formed a great bond—both had a keen interest in science, a love of the outdoors, and an affinity for having a good time.

CREDIT: DAVID ARONSON

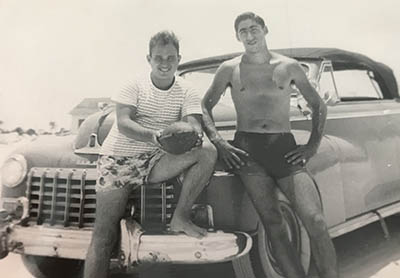

Aronson (right) and a friend lean on Nirenberg’s 1950 Dodge convertible. (Inside, the glove box has been converted into a whiskey bar.)

For my entire life I have been fascinated by my Papa’s stories about Marshall before he became the man the world knew. I never tired of hearing about Marshall and my Papa building a whiskey bar in the glove compartment of a sleek 1950 Dodge convertible, going to Daytona Beach to celebrate the 4th of July or, of course, catching hundreds of flies together. Marshall was also the person who introduced my grandfather to Sherlee Holmes on a blind date. She was a young, charismatic nursing student at a nursing school in Gainesville. Sherlee was good friends with Marshall, who was well known around the nursing school as a charmer. She went on to marry my grandfather and eventually became my grandmother.

Marshall and my Papa went their separate ways after college. My Papa was drafted into the Army and then went on to veterinary school at Auburn University (Auburn, Alabama). Marshall enrolled at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, Michigan) for his doctorate. They kept in occasional touch through the years and had the occasional meet-up including a 1980s visit to Washington, D.C., where Marshall, who had already gained a Nobel Prize and international fame, was still driving around in an old car with its bumper hanging off. He didn’t drive it much though because he spent so much time in his NIH lab.

CREDIT: JUDI PATRICK

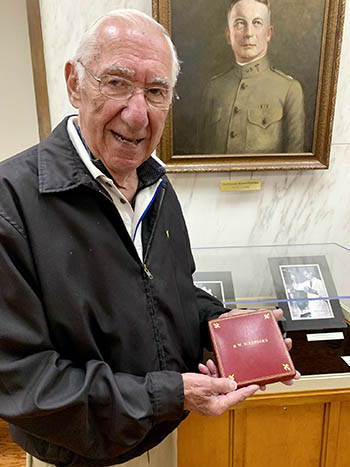

David Aronson viewed many Nirenberg-related objects at the National Library of Medicine’s History of Medicine Division and is holding the leather case with Nirenberg’s Nobel Prize gold medal. Just behind him is a display case with Nirenberg materials. The portrait hanging in background is that of Fielding Hudson Garrison (1870-1935) whose professional career was as a librarian, bibliographer, and medical historian at the Army Medical Library (later the National Library of Medicine).

Despite having become world renowned, Marshall was always keen on getting every last detail about my Papa’s life whether it was stories about his family, news about his veterinary practice, or updates on the latest advancements in animal research and medicine. Marshall’s curiosity about people was just as strong as his curiosity about science.

Although Marshall and Papa’s friendship was relatively brief, my grandfather can still describe his memories of Marshall with such clarity and detail you would have guessed many of their escapades had happened last week. He always speaks of Marshall with fondness and admiration. Many of their stories played a big role in my own upbringing. I loved hearing them, reading articles by and about Marshall, and even writing school papers on him. It wasn’t until college (at the University of Florida, where my three brothers and my parents also went), where my love of science started to blossom. I realized that all of my reading about Marshall had inadvertently given me quite the introduction to biology and genetics. Going into my junior year of college, I had the opportunity to intern at the NIH in a genetics lab within the National Institutes of Nursing Research.

In May 2019, Tara Mowery arranged for my mom (Judi Aronson Patrick), my grandfather, and me to visit NIH. Tara, who’s chief of the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM’s) Visitor Operations, set up a VIP tour for us that included visiting the Nobel Laureate Wall in the NIH Visitor Center; going to NLM to view the profile video of Dr. Nirenberg, meet the NLM director, and look at Dr. Nirenberg’s genetic-code chart in NLM’s History of Medicine Department; having lunch with two NIH historians; visiting the Marshall Nirenberg exhibit in the Clinical Center (Building 10); and meeting a few of Marshall’s colleagues. Everyone loved hearing my grandfather’s stories, and he was thrilled to share them.

CREDIT: LAURA S. CARTER

David Aronson and his family got to meet Alessandra Rovescalli, a scientist who trained in Nirenberg’s lab and remained there for 12 more years. From left: Joseph Patrick, David Aronson, Alessandra Rovescalli, and Judi Patrick.

You never know how the people you meet will end up affecting your life and how the littlest of things and occurrences can have such everlasting meaning.

David Aronson, a retired veterinarian in Pensacola, turned 90 in January 2021. He practiced veterinary medicine for more than 50 years and received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Florida Veterinary Medical Association in 2002. In addition to receiving many other awards, he served in leadership positions in several professional veterinary organizations.

Joseph Patrick is working as a data scientist for Booz Allen Hamilton’s health-consulting office (Falls Church, Virginia) and pursuing his master’s in biostatistics at George Mason University (Fairfax, Virginia). During college, he did an internship in a genetics lab within the National Institutes of Nursing Research.

This page was last updated on Thursday, February 3, 2022