Unfit to Breed: America’s Dark Tale of Eugenics

Former NIDDK Director Allen Spiegel Gives History of Medicine Lecture

CREDIT: SCREENSHOT FROM ALLEN SPIEGEL’S PRESENTATION

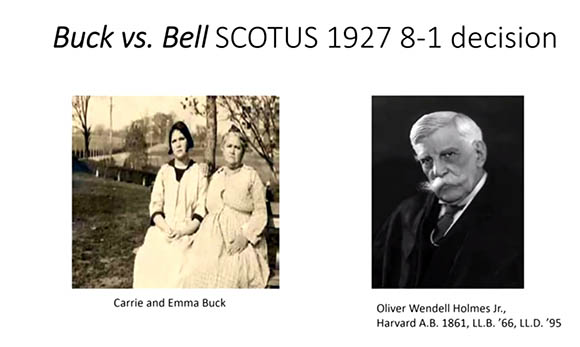

Carrie Buck and her mother (left panel) were both labelled as “feebleminded,” shorthand for unintelligent and undesirable. In the 1927 the Supreme Court case, Buck v. Bell, judges endorsed the surgical sterilization of Carrie Buck, who was pregnant due to rape at age 16. Officials at the institution where she was sent to keep the pregnancy secret wanted to sterilize her to prevent her from passing her perceived feeblemindedness to future generations. The landmark decision set a legal precedent for the roughly 60,000 other forced sterilizations that followed. (Right panel) Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. who presided over the case.

Eugenics is broadly defined as the use of selective breeding to improve the human race. The main principle behind the early eugenics movement was the assumption that all human characteristics are borne of simple inheritance. Spiegel began his lecture with a comprehensive history of the movement. He explained that the idea of eugenics was largely developed and popularized in the late 1800s by Sir Francis Galton (a cousin of Charles Darwin), who applied the principles of natural selection to the human race. His ideas took root in America in the early 1900s and were championed by Harry Laughlin (a former teacher interested in animal breeding) and Charles Davenport (a prominent biologist). When Davenport was director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor, New York), he founded the Eugenics Record Office (ERO), which became the epicenter of American eugenics; he recruited Laughlin to be ERO’s superintendent and assistant director. Davenport examined family trees (pedigrees) in order to elucidate inheritance patterns for various observable traits. Some traits had a legitimate genetic source, such as Huntington disease and hemophilia. Others, Spiegel explained, did not. Davenport “collected pedigrees of families with pauperism...and my favorite, thalassophilia—love of the sea...as if [this was passed through simple inheritance].”On April 22, 2021, Allen Spiegel gave a lecture at NIH on the unsettling history of the 20th century eugenics movement in America. Spiegel, who spent 33 years at NIH, is the former director of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1999–2006) and was dean of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York (2006–2018). He remains a faculty member at Albert Einstein, but stepping down as dean has afforded him more time to pursue personal interests, such as investigating the history of eugenics in America. The Office of NIH History invited Spiegel to share his knowledge on the subject as the first talk in the NIH “History of Medicine” lecture series.

CREDIT: OFFICE OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS, ALBERT EINSTEIN COLLEGE OF MEDICINE

Former NIDDK Director Allen M. Spiegel, gave a lecture at NIH on the unsettling history of the 20th century eugenics movement in America.

The assumption that all characteristics are genetically determined led to the widespread belief that desirable traits should be selected for. This was encouraged and celebrated through “fitter family” and “better baby” competitions, where judges rated families and children like people would rate livestock or pets at shows today. Additionally, the eugenics movement sought to eliminate undesirable traits in society—forcibly sterilizing people with unwanted characteristics to prevent their contribution to the gene pool. Each state had their own criteria for which people should be sterilized including “the feebleminded,” “moral degenerates,” “mental defectives,” and “habitual criminals.” These criteria were vague and often biased against marginalized groups such as immigrants, people with disabilities, and the poor.

Acceptance of eugenics was prevalent in American society and academia in the early 1900s. For example, many Harvard faculty and graduates espoused these principles. Additionally, well-respected figures at the time such as the Rockefeller family, the Carnegie family, and U.S. President Woodrow Wilson showed vigorous support. In fact, these principles became so popular that Nazi Germany took notice, inspiring the Holocaust. A 1934 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine even addressed this fact, lauding Germany as “perhaps the most progressive nation in restricting fecundity among the unfit,” and noting how “[the American people are probably] not ready for the adoption of the German plan.”

The eugenics movement was rife with societal bias that defined which attributes made the best individual. And, in each country where eugenics was practiced, those biases colored a broad range of what was considered genetically ideal.

Spiegel illustrated the negative consequences of biases against groups deemed inferior, citing the example of Arno Motulsky, one of 900 Jewish people seeking to escape Nazi-occupied Europe aboard the ship the St. Louis. This ship was denied entry to the United States, according to Spiegel, because of restrictions on immigrant groups considered undesirable. Motulsky was later able to emigrate to America and went on to an illustrious career as a pioneer in medical genetics. He is one of many remarkable individuals serving to demonstrate that no society practicing eugenics had accurately modeled the traits that characterize an ideal human, said Spiegel.

With the last forced sterilizations occurring in the 1960s, the eugenics movement is far from ancient history. At the end of his talk, Spiegel drew attention to advances in modern medicine that, if left unchecked, could conceivably cause a resurgence of these old ideas. Genetic testing already provides prospective parents with the opportunity to screen a fetus for genetic traits in utero, opening the potential to terminate offspring with traits unwanted by society. On the horizon, genetic-editing technologies (such as the CRISPR/Cas9 method) might allow for modification of pre-implantation cells used for in vitro fertilization, or even the cells of an adult human. While these technologies hold extraordinary possibilities for treating illness and preventing suffering, they also have the potential to be used to enhance positive traits and delete those that are simply disliked by society.

Science continues to make giant leaps that improve how we treat disease. But history cautions us to temper our enthusiasm and consider the ramifications of using new knowledge. Spiegel concluded his lecture with some thoughts to keep in mind as modern medicine pushes forward: protecting society’s marginalized groups; keeping a standard of bioethics and objectivity; and distinguishing between using technology to promote health versus using it to enhance desirable traits (and if we should even make those distinctions).

“I certainly don’t have the answers to these questions,” Spiegel said. “But I hope that [by] presenting this lecture to you...you will at least contemplate these [considerations] and...help us find a way forward.”

To view the videocast of the April 22, 2021, lecture, “A Brief History of Eugenics in America: Implications for Medicine in the 21st Century,” go to https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=41818.

Megan Kalomiris, a postbaccalaureate fellow in the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, studies norovirus. After completing her NIH training in 2021, she will be attending the Science Communications Master’s Program at the University of California at Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, California). In her spare time, she enjoys taking walks in the woods and playing games (now, virtually) with her friends.

This page was last updated on Thursday, February 3, 2022