Research Briefs

NINR: BIOMARKER IN BLOOD MAY HELP PREDICT RECOVERY TIME FOR SPORTS CONCUSSIONS

CREDIT: PAUL BURNS/BLEND IMAGES/THINKSTOCK

NINR researchers have found that measuring concentrations of tau in the blood may provide an unbiased way to determine when it’s safe for athletes to return to play after a concussion.

Despite the millions of sports-related concussions that occur annually in the United States, there is no reliable blood-based test to predict recovery and an athlete’s readiness to return to play. A new study by NINR researchers and others, however, shows that measuring concentrations of a protein called tau in the blood could potentially provide an unbiased tool to help prevent athletes from returning to action too soon and risking further neurological injury. Tau is also connected to the development of Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases and is a marker of neuronal injury after severe traumatic brain injuries.

A group of 632 soccer, football, basketball, hockey, and lacrosse athletes from the University of Rochester (Rochester, New York) first underwent preseason blood-plasma sampling and cognitive testing to establish a baseline. They were then followed during the season for any diagnosis of concussion, with 43 of them developing concussions during the study. For comparison, a control group of 37 teammate athletes without concussions was also included in the study as well as a group of 21 healthy non-athletes. After a sports-related concussion, blood was sampled from both the concussed and control athletes at six hours, 24 hours, 72 hours, and seven days post-concussion.

Concussed athletes who needed a longer recovery time before returning to play (more than 10 days post-concussion) had higher tau concentrations overall at six, 24, and 72 hours post-concussion compared with athletes who were able to return to play in 10 days or fewer. These observed changes in tau levels occurred in both male and female athletes, as well as across the various sports studied. Further research will test additional protein biomarkers and examine other post-concussion outcomes. (NIH authors: J. Gill and W. Livingston, Neurology DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003587.

NIMH, NIAAA, NICHD: SEX HORMONE-SENSITIVE GENE COMPLEX LINKED TO PREMENSTRUAL MOOD DISORDER

NIH researchers have discovered molecular mechanisms that may underlie a woman’s susceptibility to disabling irritability, sadness, and anxiety in the days leading up to her menstrual period. Such premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) affects two to five percent of women of reproductive age, whereas less-severe premenstrual syndrome is much more common. The researchers found dysregulated expression in a suspect gene complex, adding to evidence that PMDD is a disorder of cellular response to estrogen and progesterone.

The researchers studied the genetic control of gene expression in cultured white blood-cell lines from women with PMDD and control subjects. These cells express many of the same genes expressed in brain cells—potentially providing a window into genetically influenced differences in molecular responses to sex hormones. An analysis of all gene transcription in the cultured cell lines turned up a large gene complex in which gene expression differed conspicuously in cells from patients compared with those from control subjects. This ESC/E(Z) gene complex regulates epigenetic mechanisms that govern the transcription of genes into proteins in response to the environment—including sex hormones and stressors.

More than half of the ESC/E(Z) genes were overexpressed in PMDD patients’ cells compared to cells from control subjects. Paradoxically, protein expression of four key genes was decreased in cells from women with PMDD. In addition, progesterone boosted expression of several of these genes in control subjects, whereas estrogen decreased expression in cell lines derived from PMDD patients. This finding suggested dysregulated cellular response to hormones in PMDD. (NIH authors: N. Dubey, J.F. Hoffman, K. Schuebel, Q. Yuan, P.E. Martinez, L.K. Nieman, P.J. Schmidt, and D. Goldman, Mol Psychiatry DOI:10.1038/mp.2016.229.

NICHD: PARENTAL OBESITY MAY BE LINKED TO DELAYS IN CHILD DEVELOPMENT

Children of obese parents may be at risk for developmental delays, according to an NICHD study. The investigators found that children of obese mothers were more likely to fail tests of fine motor skills. Children of obese fathers were more likely to fail measures of social competence, and those born to extremely obese couples were also more likely to fail tests of problem-solving ability. In the study, authors reviewed data collected from the Upstate KIDS study (https://www.nichd.nih.gov/about/org/diphr/eb/research/pages/infant-development.aspx), which originally sought to determine whether fertility treatments could affect child development from birth through age three. More than 5,000 women enrolled in the study roughly four months after giving birth in New York state between 2008 and 2010. To assess development, researchers asked parents to complete the Ages and Stages Questionnaire after performing a series of activities with their children.

Compared with children of normal-weight mothers, children of obese mothers were nearly 70 percent more likely to have failed the test indicator on fine motor skill by age 3. Children of obese fathers were 75 percent more likely to fail the test’s personal-social domain—an indicator of how well they were able to relate to and interact with others by age three. Children with two obese parents were nearly three times as likely to fail the test’s problem-solving section by age three.

If the link between parental obesity and developmental delays is confirmed, the authors wrote, physicians may need to take parental weight into account when screening young children for delays and early interventional services. (NIH authors: E.H. Yeung, R. Sundaram, A. Grassabian, Y. Xie, and G. Buck Louis, Pediatrics 139(2):e20161459, 2017.

NIAID: INVESTIGATIONAL MALARIA VACCINE DEMONSTRATES CONSIDERABLE PROTECTION IN MALIAN ADULTS FOR DURATION OF MALARIA SEASON

CREDIT: NIAID

Adult volunteer in Mali receives the experimental malaria vaccine known as the PfSPZ vaccine.

An investigational malaria vaccine—known as the PfSPZ vaccine—given intravenously was well-tolerated and protected a significant proportion of healthy adults against infection with malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum, a malaria-causing parasite carried by mosquitoes. The study was conducted by researchers from NIAID and the University of Science, Techniques, and Technologies of Bamako, one of NIAID’s International Centers of Excellence in Malaria Research in Bamako, Republic of Mali. The study participants live in Mali, where they are naturally exposed to the parasite.

The Mali study was launched in January 2014 and enrolled 109 healthy African men and nonpregnant women ages 18 to 35 years old. Participants received either five doses of the intravenous PfSPZ vaccine or five doses of placebo (saline) over five months of the dry season at the study’s clinical site in the village of Donéguébougou in rural Mali.

Clinical staff then monitored the participants during the six-month rainy malaria-transmission season for malaria parasites in the blood. The investigators reported that the vaccine candidate was well-tolerated and safe with no serious adverse events. Among the 40 participants who received the placebo, 93 percent (37 participants) developed P. falciparum malaria infections; by comparison, 66 percent (27 participants) of the participants who received the PfSPZ vaccine (41 participants) developed malaria infection. The vaccine demonstrated a 48 percent protective efficacy by time-to-first-positive malaria blood smear and 29 percent efficacy by proportion of participants with at least one positive malaria blood smear during a full 20-week malaria-transmission season. By both measures of protective efficacy, there was statistically significant protection in the vaccine group compared with the placebo group.

The vaccine-induced antibody response was considerably lower in the Mali study, however, than in the U.S. trial even though study participants received the same vaccine regimen. The poor antibody response to PfSPZ vaccine among Malians could have been because of the participants’ lifelong exposure to P. falciparum, according to the study authors. A preventive malaria vaccine employed in mass vaccination programs would need to prevent malaria infection or transmission in at least 80 percent of recipients throughout the malaria-transmission season.

Clinical trials now underway in Africa, Europe, and the United States have been designed to boost the PfSPZ vaccine’s efficacy by increasing dosages and varying the timing and number of doses. The experimental vaccine is also being examined in demographic groups other than healthy adults, including adolescents, children, and infants. (NIH authors: S.A. Healy, I. Zaidi, K. Ding, S. Wong-Madden, M. Walther, P.E. Duffy, E.E. Gabriel, M.P. Fay, E.M. O’Connell, and T.B. Nutman, Lancet DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30104-4; http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(17)30104-4/abstract)

NINDS, NHGRI, NIAID: NODDING SYNDROME MAY BE CAUSED BY RESPONSE TO PARASITIC PROTEIN

CREDIT: AVINDRA NATH, NINDS

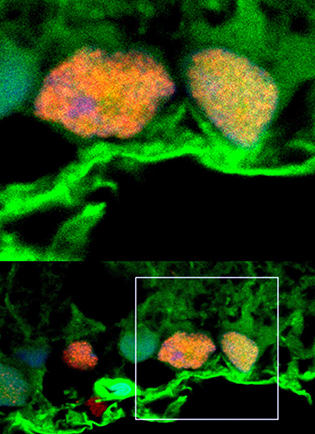

New clues to nodding syndrome—NIH scientists discovered leiomodin-1 (green) inside human brain cells. This study suggests that nodding syndrome may be an autoimmune disease.

NIH researchers have uncovered new clues to the link between nodding syndrome, a devastating form of pediatric epilepsy found in specific areas of east Africa, and a parasitic worm that can cause river blindness. Many studies have reported an association between nodding syndrome and Onchocerca volvulus, a parasitic worm that can also cause river blindness. The worm is spread by black flies in specific geographic areas where clusters of nodding syndrome have been observed. However, it was unclear whether the worm itself caused this neurological disorder. In this study, the researchers compared serum samples from patients with nodding syndrome and with those from healthy control subjects who all lived in the same village in Uganda.

The results showed high concentrations of antibodies to leiomodin-1 in the samples obtained from the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with nodding syndrome. Previous studies had shown leiomodin-1 is found in muscles, but this was the first time researchers saw it in the nervous system. These results may ultimately provide a diagnostic test that can help identify individuals at risk for developing nodding syndrome.

The researchers are currently developing an animal model of the syndrome to further study the disease and test potential therapies. (NIH authors: T.P. Johnson, R. Tyagi, P.R. Lee, M-H. Lee, K.R. Johnson, J. Kowalak, A. Elkahloun, M. Medynets, A. Hategan, J. Kubofcik, T.B. Nutman, and A. Nath, Sci Transl Med DOI:10.1126.

NIAID: HOW ANTIBODY TREATMENT LED TO SUSTAINED REMISSION OF HIV-LIKE VIRUS

The presence of the protein alpha-4 beta-7 integrin on the surface of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and its monkey equivalent—simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)—may help explain why an antibody protected monkeys from SIV in previous experiments, according to a new NIH study. In October 2016, NIAID researchers reported (https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/scientists-nih-and-emory-achieve-sustained-siv-remission-monkeys) that they had achieved sustained SIV remission in monkeys using a monkey antibody similar to the human drug vedolizumab, which is approved by the FDA for treating ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. The mechanism behind this observation has been unclear, but the new study provides clues.

Scientists have known that alpha-4 beta-7 integrin is a gut-homing receptor present at high concentrations on the immune-system cells that HIV and SIV preferentially infect. In the new study, scientists found that maturing HIV and SIV particles acquire alpha-4 beta-7 integrin as they emerge from an infected cell, presenting researchers with a new target for HIV prevention and treatment and shedding light on how HIV disease develops.

The scientists’ next step is to conduct a study to try to prove that the presence of alpha-4 beta-7 integrin on SIV explains the protective effect of the anti–alpha-4 beta-7 antibody observed in the earlier monkey experiments. Meanwhile, the NIAID researchers are enrolling participants in a clinical trial to determine whether short-term treatment with vedolizumab in combination with antiretroviral therapy can generate sustained HIV remission in people living with HIV. (NIH authors: C. Guzzo, D. Ichikawa, C. Park, C. Rehm, C. Cicala, J. Arthos, A.S. Fauci, J. Kehrl, and P. Lusso, Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Feb 13–16, 2017, Abstract Number: 64LB.

NICHD: HAIR ANALYSIS MAY HELP DIAGNOSE CUSHING SYNDROME

Diagnosing Cushing syndrome, a rare and potentially fatal disorder in which the body overproduces the stress hormone cortisol, is difficult and time consuming. It involves analyzing blood and urine tests, brain-imaging tests, and tissue samples. But, according to a study conducted by researchers at NIH and elsewhere, analyzing hair samples for cortisol concentrations tracked closely with standard techniques for diagnosing the syndrome and so may provide a less-invasive screening test.

The study enrolled 30 patients with—and 6 patients without—Cushing syndrome. Because the condition is rare, it’s hard to recruit a large number of patients. Still, the researchers believe their study is the largest of its kind to compare hair cortisol concentrations to diagnostic tests in Cushing patients. The authors note that further studies are needed to confirm their findings. (NIH authors: A. Hodes, M.B. Lodish, A. Tirosh, E. Belyavskaya, C.S. Lyssikatos, A. Demidowic, J. Swan, N. Jonas, C.A. Stratakis, M. Zilbermint, Endocrine DOI:10.1007/s12020-017-1231-7.

NEI: STEM-CELL SECRETIONS MAY PROTECT AGAINST GLAUCOMA

CREDIT: BEN MEAD, NEI

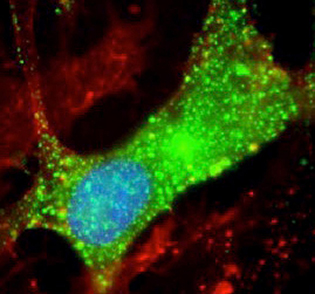

Microscopy shows exosomes (green) surrounding retinal ganglion cells (orange and yellow).

NEI scientists found that stem-cell secretions, called exosomes, promote the survival of retinal ganglion cells in rats. The findings point to potential therapies for glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness in the United States. In a rat glaucoma model, the researchers studied the effects of exosomes isolated from bone-marrow stem cells on retinal ganglion cells. Exosomes were injected weekly into the rats’ vitreous, the fluid within the center of the eye. Before injection, the exosomes were fluorescently labeled, allowing the researchers to track the delivery of the exosome cargo into the retinal ganglion cells.

Exosome-treated rats lost about a third of their retinal ganglion cells after optic-nerve injury compared with a 90 percent loss among untreated rats. Stem-cell exosome-treated retinal ganglion cells also maintained function, according to electroretinography, which measures electrical activity of retinal cells. The researchers determined that the protective effects of exosomes are mediated by microRNA. Further research is needed to understand more about the specific contents of the exosomes. (NIH authors: B. Mead and S. Tomarev, Stem Cells Transl Med DOI:10.1002/sctm.16-0428.

NCI, NIDA: PREMATURE DEATH RATES DIVERGE IN THE UNITED STATES BY RACE AND ETHNICITY

Premature death rates have declined in the United States among Hispanics, African-Americans, and Asians and Pacific Islanders (APIs)—in line with trends in Canada and the United Kingdom—but have increased among whites and American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/ANs), according to a comprehensive study of premature death rates for the entire U.S. population from 1999 to 2014. This divergence was reported by researchers at NCI and NIDA.

Declining rates of premature death (deaths among 25- to 64-year-olds) among Hispanics, African-Americans, and APIs were due mainly to fewer deaths from cancer, heart disease, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The decline reflects successes in public-health efforts to reduce tobacco use and medical advances to improve diagnosis and treatment. Whites also experienced fewer premature deaths from cancer and, for most ages, fewer deaths from heart disease. Despite these substantial improvements, overall premature death rates still remained higher for black men and women than for whites.

In contrast, overall premature death rates for whites and AI/ANs were driven up by dramatic increases in deaths from accidents (primarily drug overdoses) as well as from suicide and liver disease. Among 25- to 30-year-old whites and AI/ANs, the investigators observed increases in death rates as high as two percent to five percent per year, comparable to increases observed at the height of the U.S. AIDS epidemic. The results of the study suggest that, in addition to continued efforts against cancer, heart disease, and HIV, there is an urgent need for aggressive actions targeting emerging causes of death, namely drug overdoses, suicide, and liver disease. (NIH authors: M.S. Shiels, P. Chernyavskiy, W.F. Anderson, A.F Best, P. Hartge, P.S Rosenberg, D. Thomas, N.D. Freedman, and A. Berrington de Gonzalez, Lancet DOI:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30187-3.

NCI, NHGRI, NIDCD, NIEHS: GENOMIC FEATURES OF CERVICAL CANCER IDENTIFIED

Investigators with The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network have identified novel genomic and molecular characteristics of cervical cancer that will aid in the subclassification of the disease and may help target therapies that are most appropriate for each patient. The new study, a comprehensive analysis of the genomes of 178 primary cervical cancers, found that over 70 percent of the tumors had genomic alterations in either one or both of two important cell-signaling pathways. The researchers also found, unexpectedly, that a subset of tumors did not show evidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. The study included authors from NCI, NHGRI, NIDCD, and NIEHS.

Of particular interest was the identification of a unique set of eight cervical cancers that showed molecular similarities to endometrial cancers. These endometrial-like cancers were mainly HPV-negative, and they all had high frequencies of mutations in the KRAS, ARID1A, and PTEN genes. The identification of HPV-negative endometrial-like tumors confirms that not all cervical cancers are related to HPV infection and that a small percentage of cervical tumors may be due to strictly genetic or other factors. The authors noted that an important question raised by this study is whether HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors will respond differently to targeted therapies. (NIH authors: N.S. Wentzensen, I. Felau, J.C. Zenklusen, C. Bodelon, J.A. Demchok, L. Yang, M.I. Sheth, M.L. Ferguson, R. Tarnuzzer, H. Yang, M. Schiffman, J. Zhang, Z. Wang, T.A. Davidsen, C.M. Hutter, H.J. Sofia, C. Van Waes, Z. Chen, A.D. Saleh, H. Cheng, D.A. Gordenin, K. Chan, S.A. Roberts, and L.J. Klimczak, Nature DOI:10.1038/nature21386.

NCI, NHLBI, CC: EARLY-PHASE TRIAL DEMONSTRATES SHRINKAGE IN PEDIATRIC NEURAL TUMORS

In an early-phase clinical trial of a new MEK inhibitor, selumetinib, children with the genetic disorder neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) and plexiform neurofibromas (tumors of the peripheral nerves) tolerated selumetinib and, in most cases, responded to it with tumor shrinkage. NF1 affects 1 in 3,000 people. The multicenter phase 1 clinical trial included 24 patients, was led by NIH investigators, and was conducted at the NIH Clinical Center and three participating sites.

NCI is currently sponsoring an ongoing phase 2 trial of the drug for adults with NF1, in which serial tissue samples are being obtained. This study should provide information about possible mechanisms of resistance to selumetinib. In addition, a larger phase 2 pediatric trial is enrolling patients and should help establish the efficacy of selumetinib treatment in children. In this trial, in addition to measuring tumor volume, the researchers are assessing the effect of selumetinib on plexiform neurofibroma-related disfigurement, pain, quality of life, and function. (NIH authors: E. Dombi, A. Baldwin, L.J. Marcus, E. Dombi, P. Whitcomb, S.I. Martin, R. Ershler, P. Wolters, J. Therrien, J. Glod, A. Brofferio, A.J. Starosta, A. Gillespie, A.L. Doyle, and B.C. Widemann, N Engl J Med 375:2550–2560, 2016.

NIDCR, NIAID, NCI: MECHANICAL DAMAGE CAUSED BY CHEWING REGULATES TH17 CELL RESPONSES IN THE MOUTH

CREDIT: NIKI M. MOUTSOPOULOS, NIDCR

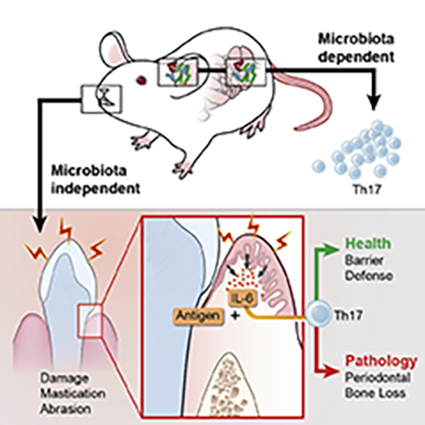

Th17 cells are key mediators of immunity at barrier sites such as the oral cavity. The factors that control these cells differ depending on cues unique to each site’s local environment.

The immune system performs a remarkable balancing act at barrier sites such as the skin, mouth, and intestines, by fighting off harmful pathogens while tolerating normal flora. Multiple immune cell types protect these sites, including T helper 17 (Th17) cells. Although Th17 cells are known to be important in immunity at barrier surfaces, exaggerated Th17 cell responses have been linked to the oral inflammatory-disease periodontitis. Understanding the tissue-specific factors that regulate immunity at the oral barrier is critical and may lead to new ways to treat this common inflammatory condition.

In a new study, NIDCR researchers and scientists from the University of Manchester (Manchester, United Kingdom) have shown that in the mouth, mechanical damage caused by chewing controls physiologic Th17 cell responses. Mice fed a soft-food diet requiring minimal chewing accumulated fewer Th17 cells than mice fed a normal or hard-food diet. The investigators also showed that the signaling molecule interleukin 6 (IL-6) mediates the damage-induced rise in Th17 cell numbers. Unlike normal mice, mice lacking IL-6 failed to accumulate Th17 cells in response to a hardened diet or to oral mechanical abrasion.

This work has revealed that Th17-cell regulation in the mouth differs from that at other barrier sites such as the skin and intestines, where certain microbes have been shown to stimulate Th17-based immunity. The investigators concluded that factors that control Th17 cells differ depending on the unique characteristics and environment of each body site. (NIH authors: N. Dutzan, L. Abusleme, T. Greenwell-Wild, N. Bouladoux, L. Brenchley, G. Calderon, T. Break, M. Lionakis, G. Trinchieri, Y. Belkaid, and N. Moutsopoulos, Immunity 46:133–147, 2017.

[SUBMITTED BY CATHERINE EVANS, NIDCR]

This page was last updated on Monday, April 11, 2022