NIH in History

Hidden Treasures Discovered in Building 38: Proof That NLM is NIH’s Own Treasure Island

Imagine a book that features a life-sized human anatomy manikin; an overview of palm reading in Renaissance Europe; a post–World War I silent film of schizophrenic patients; the first systematic study of human motion; health and hygiene puzzle blocks from Communist China; and Adolf Hitler’s medical records. Such a book exists, in the form of Hidden Treasure, which was published in honor of the NIH National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) 175th anniversary (celebrated in 2011) and highlights 80 of the library’s most mysterious and unusual items.

It was no easy task for the book’s editor, NLM historian Michael Sappol, to choose which of library’s 17 million treasures to include. He selected items for their visual appeal and ability to represent the breadth of NLM’s rich collection—the charming and the disturbing; the beautiful and the repulsive; the intriguing and the informative—and included books, pamphlets, flyers, manuscripts, journals, lithographs, letters, postcards, posters, magazines, engravings, cartoons, objects, photographs, films, sound recordings, and slides. He also invited distinguished scholars, artists, collectors, journalists, and physicians to write commentary essays about each of the treasures.

Capturing images of the final 80 was not easy either, said Arne Svenson, the New York photographer NLM hired for the project. More challenging than shooting in the library’s cramped spaces and under “haunted house at high noon” lighting, said Svenson, was “finding creative ways to shoot books, books, and more books and make each resultant photo a compelling, individualized statement.” To combat the limited space, he wedged himself between shelves. To counter the poor lighting, he used strobe lights, ordinary light bulbs, and even flashlights. And to keep the settings interesting, he and the book’s designer, Laura Lindgren, scavenged the library’s halls for unique locations. “A shelf of books, corners of rooms, file cabinets—anything and everything was a candidate for ambient background scenes,” he said.

What follows is a sampling of the diamonds within the crown of Hidden Treasure’s jewels.

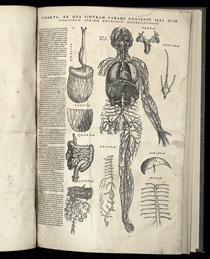

The Anatomical Paper Doll Epitomized

The Epitome (1543) by Andreas Vesalius;

Essay by Andrea Carlino, who teaches the history of medicine at the University of Geneva

Composed by Flemish physician Andreas Vesalius, this book contains large woodcuts of human forms and illustrations of organs, vessels, and other bits of human anatomy, as well as instructions on how to cut them out “to build [a] multilayered anatomical paper doll and then glue it to one of the muscle figures [in] the book,” Carlino wrote. Vesalius believed performing this exercise would enforce understanding of the composition and spatial arrangement of internal organs. NLM’s copy of the book “is noteworthy because it is one of the few 1543 paper copies that have survived the spoiling effects of time—and the scissors of readers and owners.”

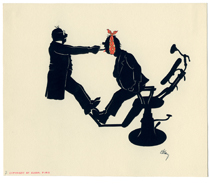

Slide Show Follies As Therapy

St. Elizabeths Magic Lantern Slide Collection (1855-1890s); essay by Benjamin Reiss, a professor of English at Emory University (Atlanta)

“Given that many patients were delusional and/or medicated with dream-inducing opiates, one wonders about the wisdom of serving up these ready-made hallucinations, magnified to terrifying proportions,” Reiss wrote. But some psychiatrists believed that “asylum amusements should feature techniques of ‘revulsion’—that is, psychological interventions that would cause patients to recoil from their delusions by externalizing them.Originally the Government Hospital for the Insane, St. Elizabeths is a Washington, D.C., psychiatric hospital that opened in 1855. Magic lantern displays (primitive slide shows) were developed in the early 1850s by Dr. Thomas Kirkbride of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane and by two German émigré photographers for patient therapy and entertainment. Viewing images was intended to temporarily relieve patients’ delusions. Magic lantern slides ranged from the instructive, such as illustrations of the hazards of alcohol and tobacco, to the bizarre, such as the image depicted here of “The Attack of the Monster [Flea],” in which a magnified flea is threatening an ax- and shears-wielding man.

The Lost Art of Dental Slapstick

Dental Cartoons (1948) by Otto Elkan; Essay by Alyssa Picard, author of Making the American Mouth: Dentists and Public Health in the Twentieth Century

These wry cartoons “not only document the international spread of American dental technology [in the 1940s] but also a transatlantic cultural preoccupation with access to good professional dental care, particularly in wartime,” Picard wrote. “During World War II—when nearly all of Europe’s professionally trained dentists had entered military service, been forced to flee, or been put in concentration camps—access to good dental care was severely restricted.”

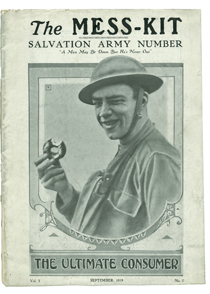

“Funny-isms” and “Ward Gossip”

The Mess Kit and The Silver Chev’ (1919); essay by Jeffrey S. Reznick, NLM

“Magazine work served to distract from bullet, shell, and bayonet wounds, influenza and other infectious diseases, gas exposure, gangrene, and shell shock [and provide] ‘safety valves’ to help relieve the stress experienced by frontline soldiers and their caregivers,” he continued. “Editors playfully interwove a variety show of cartoons, embellishments, photographs, and texts.In the aftermath of World War I, at least 50 military hospitals produced in-house magazines between 1918 and 1919. “Endorsed by the Surgeon General’s Office, magazines such as The Mess Kit of Camp Merritt Base Hospital, New Jersey, and The Silver Chev’ of Camp Grant Base Hospital, Illinois, and The Come-Back of Walter Reed General Hospital, Washington, D.C., were brought to life by wounded soldiers and military staff who contributed articles, jokes, poems, illustrations, and other material,” wrote Reznick.

The Phantom of the Anatomy Lecture

White’s Physiological Manikin (1886); essay by Michael Sappol, NLM

Described by Sappol as “a gadget that does too much,” this life-sized manikin has numerous flaps and openings revealing different layers of the human anatomy. In 1887, 25 states required the teaching of physiology in public schools. Three-dimensional, dissectible visual aids were needed, but the papier-mâché manikins imported from France ranged from $250 to $1,500. White’s Manikin was a mere $35 and it remained for 20 years the visual anatomy tool of choice for many U.S. public schools. To photograph it artistically, Arne Svenson said he “added a totally incongruous contemporary red office chair as a way to create not only scale and a sense of place, but [also] a touch of humor to this somewhat grisly tableau.”

Window Into History

Hidden Treasure “opens a window onto the diversity of the collection [and] onto the history of the library itself,” said Jeffrey Reznick, chief of NLM’s History of Medicine Division.

In 1836, the NLM was just a small collection of medical books on a shelf in the Office of the Surgeon General of the Army. Today it’s housed at NIH and is the world’s largest biomedical library, with a collection of over 17 million items in more than 150 languages. NLM also provides automated Internet services—including MedlinePlus, PubMed, and PubMed Central—that “deliver trillions of bytes of health data crucial to the lives of millions of people around the globe,” said Reznick. “These collections belong to the public [and] people are welcome to look at any of this to learn more about it.”

NLM is not a circulating library. Visitors, however, are welcome to apply for a free library card to access NLM matrials (including those featured in Hidden Treasure) in one of the reading rooms. For more information go to http://www.nlm.nih.gov/about/visitor.html. To learn about the collections and resources in NLM’s History of Medicine Division, visit http://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/index.html In addition, Hidden Treasure is available through all major online booksellers as well as from the FAES Scientific Bookstore, Level B1, in Building 10.

This page was last updated on Monday, May 2, 2022