Yanny or Laurel? Relax. Everyone's a Winner.

Is the Yanny vs. Laurel debate tearing your office or lab apart? Well, according to NIH IRP investigators, there's no true answer to what this word is. As brain expert Mark Hallett, M.D., of the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke puts it, "Perception is not reality, however real it seems."

To say the word is really "laurel" is a stretch. Yes, it appears that the sound originated on the Vocabulary.com entry for the word "laurel," defined as the wreath one wears as a symbol of victory. But the sound making its rounds on the internet is a distorted version of that original audio snippet. Those of us identifying that sound as "laurel" have no special right to wear the laurel.

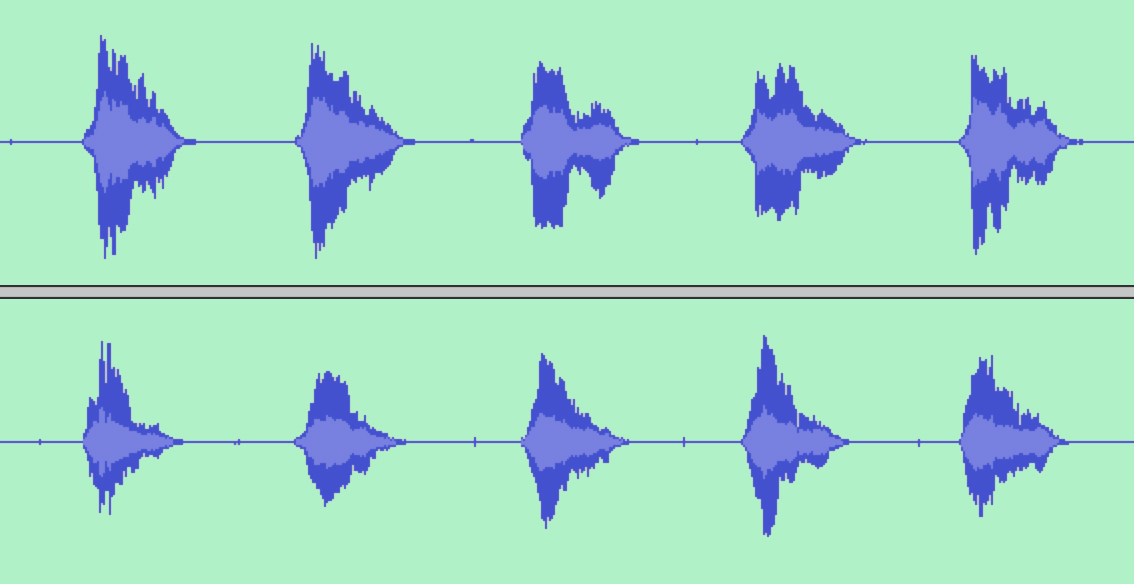

Audio waveforms of the words "yanny" (top) and "laurel" (bottom) look similar, so it's no surprise that listeners can hear either word in the controversial recording.

Your personal interpretation of this sound is less about the frequencies you can physically perceive and more about the frequencies your brain expects or desires to hear, according to Nadia Biassou, M.D., Ph.D., of the NIH Clinical Center, who studies the relationship between brain and language. Biassou's doctoral dissertation concerned auditory illusions similar to the Yanny/Laurel sound.

Most of us would likely hear "laurel" in the original audio because that is the intent of the audio. You see that big word "laurel" on this webpage, see the word defined, hear it in crystal-clear audio, and see no reference to anything labeled "yanny," which, of course, isn't a word at all.

The audio file that appeared on Instagram and then on Reddit and Twitter is distorted. And, given incomplete information — whether it is visual or auditory — your brain will try to fill in the missing pieces to make sense of the input. This is happening below the level of consciousness.

If you have taken the Yanny/Laurel survey, you encountered an inherent bias. The survey does not ask "what is this sound" but rather "which word is this, yanny or laurel?" So, that immediately limits other interpretations and frames the discussion. Given a choice of two words, listeners tend to gravitate to one based on past experience, preference, and even native tongue. Biassou noted that, for example, because the Japanese language doesn't distinguish between the letters r and l, Japanese speakers likely would hear "yanny". (Our informal survey among native Japanese speakers confirmed this.)

"The auditory perception is, in part, dependent on the bottom-up physical acoustic cues, but the interpretation of those auditory cues can be affected by what cues are attended to and what the brain is expecting to hear statistically," Biassou said.

Optical illusions — such as the two faces or vase, or the "Young Woman, Old Woman Ambiguous Figure" — present a similar phenomenon. There's nothing wrong with your vision if you can't see one or the other, as there is nothing (likely) wrong with your hearing if you can't hear "yanny" instead of "laurel."

The caveat here is that "yanny" is high frequency and "laurel" is low frequency. If you have noise-induced hearing loss, you may have difficulty discerning "yanny" — similar to how the word "taste" might be harder for you to hear than "flavor."

"Perception is something the brain makes up from expectation and sensory input," said Hallett, whose primary research is in motor control but who dabbles in all things cognitive. "Hearing loss modifies the bottom-up [sensory] signal and hence will alter how easy it is to change. Native language will likely modify both top-down expectation of sounds and possibly the pipeline for analyzing bottom-up signals."

For the record, this writer first heard "yanny" but has since learned to toggle between the two words by repeating one or the other before listening to it. Biassou, a native French speaker, first heard "laurel." And Hallett? He joked that he could only hear "jerry."

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023