Inside the NIH Brain Bank

IRP Group Supports Neuropsychiatric Research

Brains donated to NIH’s Human Brain Collection Core are fueling research into psychiatric conditions like depression and schizophrenia.

More than half of Americans are registered organ donors, signed up to gift organs like kidneys and livers to patients in need of a transplant when they die. However, far fewer people have signed up to donate their brains to biomedical research upon their deaths. At NIH, the Human Brain Collection Core (HBCC) acts as a steadfast steward of this precious and scarce scientific resource, giving the brains of deceased donors a second life as a key driver of life-changing neuropsychiatric research.

Nearly 60 million adults in the U.S. suffer from a psychiatric disorder, and examining the brains of these individuals is indispensable for determining the molecular mechanisms underlying these diseases. Consequently, the HBCC provides invaluable assistance to scientists seeking to improve our understanding and treatment of such conditions. In recognition of World Mental Health Day today, let’s take a glimpse into how the Core is accelerating investigations into the mass of gray and white matter that makes each of us who we are.

To provide tissue samples and data to scientists both within and outside the NIH Intramural Research Program, the HBCC must first obtain that material itself. The Core collects precious human brain tissue and blood samples from individuals who had been diagnosed with mental illnesses such as depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and schizophrenia, as well as people who died by suicide. They also collect brains donated from individuals who don’t have a history of mental illness, which are necessary for comparison.

“The overall mission is to make this very precious resource as available as possible to other investigators and, in return, we expect them to share the data they derive from our tissues on public websites that can be accessed by the scientific community,” says Stefano Marenco, M.D., the HBCC’s acting director. “The ultimate goal is to discover what specific molecular differences exist between patients with psychiatric disorders and those without.”

Dr. Stefano Marenco is the current acting director of the HBCC.

The HBCC essentially has two halves: intake and distribution. Jonathan Sirovatka, the intake coordinator and neuropathology technician for the HBCC, handles the former. The HBCC’s donors can be any age from infancy to the elderly, but their brains cannot show any signs of infectious disease or physical trauma, and they cannot have suffered from neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease. Donors are referred to the HBCC by one of the two medical examiners in Virginia that the group currently works with. The Core receives about 50 donations per year, although it is working to build new relationships with other organizations to increase that number.

“We are lucky to have partners who understand the importance of this research and are willing to dedicate time and staff to helping us support it, even under the severe logistical and financial challenges they face,” Sirovatka says.

One of the things that makes the donations difficult — and all the more precious — is that these are not planned donations. Rather, Sirovatka approaches the families within 24 hours of their loved one’s death and asks if they would agree to the donation.

“It’s an unexpected call and these are generally families who have never considered this,” Sirovatka says. “We receive a very wide range of reactions across the emotional spectrum. Everyone handles grief differently. Some are enthusiastic about contributing to medical research. On the other end, some are angered at being asked. You just have to handle it with a great deal of sensitivity, respect, and patience.”

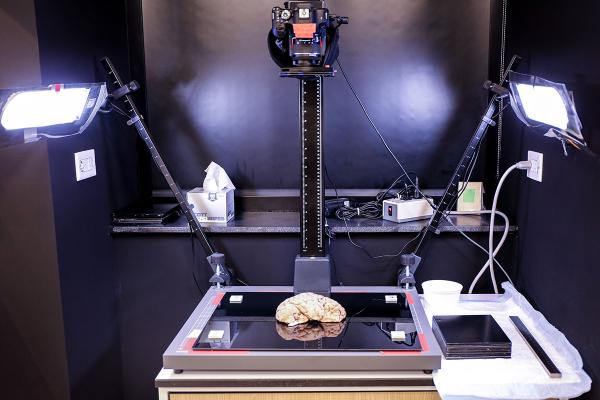

HBCC intake coordinator Jonathan Sirovatka takes a 3D scan of a donated brain.

Once the family gives permission and the brain is donated, the next steps take place very quickly before the tissue can deteriorate. An HBCC staff member or courier will promptly collect the brain and bring it to the NIH Clinical Center, where it undergoes very detailed processing. First, a 3D scan of the brain is obtained, and then the brain is cut into sections using a 3D-printed mold designed in collaboration with NIH’s Quantitative MRI (qMRI) Core and printed by the NIH Section on Instrumentation. The resulting 85-90 brain slices are photographed, individually labeled, barcoded, flash-frozen, and vacuum sealed for long term storage. The Core also collects detailed medical histories from family members and medical records from healthcare providers, reconstructing the medical and psychiatric history of the brain donor. Finally, IRP staff clinician Pavan Auluck, M.D., Ph.D., does an extensive diagnostic neuropathological evaluation of each brain, which is conveyed back to the medical examiner who provided the donation to the Core.

HBCC staff use this 3D-printed mold to divide donated brains into slices.

Then the brains are put to use. The HBCC receives about 50 requests for brain tissue from researchers each year, each of which results in the distribution of only the specific portion of the brain needed for that scientist’s study. The requests go through an approval process with an oversight committee, and the HBCC will subsequently provide the sample or prepare slides. Sometimes they go further, extracting DNA or RNA from donated brains.

“We’ll put that extra amount of work into satisfying requests because we can keep some of these resources for future studies,” Dr. Marenco says, including the HBCC’s own research, on which it collaborates with researchers both within and outside the IRP.

Of course, as information learned from donated tissue expands our understanding of our brains, changes in the field of neuroscience influence the activities of the HBCC in turn. For example, when NIH’s Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative began providing funding for cutting-edge neuroscience research, the HBCC team realized that in order to map all the cell types and regions in the brain, researchers would need thinner brain slices. And that’s not the only way the Core’s workflow has changed since it was converted in 2014 from a lab focused on schizophrenia research, which had been collecting brains since the early 1990s.

HBCC staff members use this setup to take high-quality photographs of the brain as a whole and individual slices.

“We also adopted new technology that allows us to do 3D scans of the surface of the brain and then reorganize our 2D photographs into a 3D version that looks very much like an MRI,” Dr. Marenco says. The HBCC uses those reconstructions to align the 2D brain images with brain atlases to more precisely define anatomy and support research.

In addition to its endeavors that are more directly tied to research, the HBCC also works closely with the NIH NeuroBioBank and other programs to standardize procedures and develop and improve practices for brain donation and the handling of donated tissue. The Core also does what it can to inform the public about the Brain Donor Project, where any person can sign up as a prospective brain donor.

“That’s something we like to spread the word about because few people are aware of brain donation,” Sirovatka says.

After it is processed by HBCC staff, donated brain tissue is vacuum-sealed and frozen for long-term storage until it is sent out to researchers who request it.

As rare as brain donations are, they punch way above their weight in terms of their value to the field of neuroscience. Some of the most important questions about our brains can only be answered by gaining access to the wrinkled mass of cells that is normally encased within our skulls. For that reason, resources like the HBCC play an essential role in research that could one day lead to new treatments for psychiatric conditions.

“We’re generating a new foundation of knowledge that might radically change the way we think of psychiatric disorders,” Dr. Marenco says. “This is the ultimate prize: changing a discipline that is currently based just on combinations of symptoms for diagnosis into one that is based on identifiable biological mechanisms. That would allow us to treat people with medication that is correct for their biology rather than just their symptoms, and it may even be curative.”

“Our small group of 15 staff members works tremendously hard to make the donations as useful as they can possibly be,” Sirovatka adds. “We want to obtain the most scientific knowledge from every donation. That’s the goal for everyone here because this is one of the most precious gifts a family can give.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

If you are in crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988, available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The Lifeline provides confidential support to anyone in suicidal crisis or emotional distress. Support is also available via live chat . Para ayuda en español, llame al 988.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Thursday, October 10, 2024