Rare Footage of FDR at NIH

On October 31, 1940, just days before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt would be elected to an unprecedented third term as President of the United States, he traveled to Bethesda to dedicate the National Cancer Institute and the new campus of what was then the National Institute of Health (NIH), before it would eventually become known in plural form—National Institutes of Health—as multiple units were established over subsequent years.

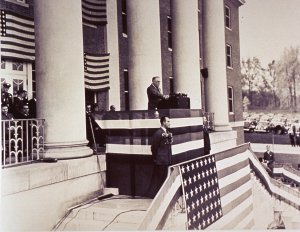

President Roosevelt at NIH

National Library of Medicine #A030309

That late October afternoon, Roosevelt stood on the steps of the new main NIH building, ready to address a crowd of 3,000 people. Still relevant today, in a variety of contexts, are the subjects he discussed: the need for preparedness in light of war and for research into deadly diseases, recent improvements in public health and health care, and hope that the research conducted at NIH would lead to new cures for and even the prevention of disease.

Today, the National Library of Medicine is making the film of Roosevelt’s speech publicly available for the first time, nearly 74 years after the President made his speech. Sound recordings, transcripts, and photographs of this event have been available publicly for many years. Our research suggests, however, that this rare film footage has not been seen publicly since its recording and may no longer exist anywhere else.

The live footage of the speech was given to NLM many years ago by the National Archives and Records Administration. The recording does not appear to have been professionally produced, although news organizations such as CBS were present on that day. The camera is unsteady in places, a hand sweeps across the lens, and the filming starts and stops, though it isn’t known whether this is a result of the original filming or of later editing.

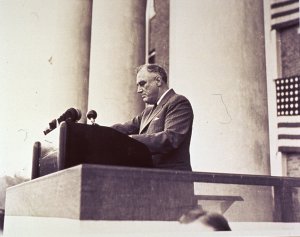

While we have long been able to hear Roosevelt’s support for public health and medical research, now we can see him state some of his powerful words from this important speech, and truly appreciate the experience of being in the audience on that historic day. The President’s concluding words capture the weight of the moment: “Today the need for the conservation of health and physical fitness is greater than at any time in the nation’s history. In dedicating this Institute, I dedicate it to the underlying philosophy of public health, to the conservation of life, to the wise use of the vital resources of our nation. I voice for America, and for the stricken world, our hopes, our prayers, our faith, in the power of man’s humanity to man.”

Five years before Roosevelt’s dedication, in 1935, Luke and Helen Wilson had donated land in Bethesda, Maryland, to the government to be used as the new home of the National Institute of Health. At the dedication, President Roosevelt thanked Mrs. Wilson for the gift she and her husband had made to and for the benefit of the nation, “For the spacious grounds on which these buildings stand we are indebted to Mr. and Mrs. Luke I. Wilson, who wrote me in 1935, asking if part of their estate at Bethesda, Maryland, could be used to the benefit of the people of this nation. I would tell her now as she sits beside me that in their compassion for suffering, their hope for human action to alleviate it, she and her husband symbolized the aspirations of millions of Americans for a cause such as this. And we are very grateful.”

The Wilsons’ donated their land shortly before the President signed the Social Security Act in 1935. The Act contained provisions meant to assist in “establishing and maintaining adequate public health services” throughout the country. Roosevelt made certain in his speech to pointedly address those who opposed some of his proposed health care initiatives, stating that “neither the American people nor their government intend to socialize medical practice any more than they plan to socialize industry.”

The possibility of the United States entering the war in Europe was also clearly on the President’s mind. In his speech, he tied together the “strategic importance of health” with the need for the nation to be prepared for war, saying, “The total defense that we have heard so much about of late—that total defense which this nation seeks—involves a great deal more than building airplanes and ships and guns and bombs, for we cannot be a strong nation unless we are a healthy nation, and so we must recruit not only men and materials, but also knowledge and science in the service of national strength.”

President Roosevelt at NIH

National Library of Medicine #A030308

Roosevelt lauded the past work of the National Institute of Health and emphasized the need to be vigilant against illnesses from abroad. “These buildings, which we dedicate, represent new and improved housing for an institution which has a long and distinguished background of accomplishment in this task of research… Now that we are less than a day by plane from the jungle-type yellow fever of South America, less than two days from the sleeping sickness of equatorial Africa, less than three days from cholera and bubonic plague, the ramparts we watch must be civilian in addition to military.”

In his remarks, the President singled out the new National Cancer Institute (NCI) that he was dedicating. He praised the Institute, stating “It is promoting and stimulating cancer research throughout the nation; it is bringing to the people of the nation a message of hope because many forms of the disease are not only curable but even preventable. Beyond this, it is doing research here and in many universities to unravel the mysteries of cancer. We can have faith in the ultimate results of these efforts.”

It is our honor and privilege to make this film footage available now as excitement is building for the upcoming PBS broadcast of the new Ken Burns documentary, The Roosevelts: An Intimate History, a landmark project that was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities, with whom NLM is working on initiatives of common interest.

For their assistance in determining what research suggests to be the uniqueness of this footage, we thank our colleagues in the NLM’s Audiovisual Program and Development Branch of the Lister Hill National Center for Biomedical Communications, the NIH Office of History, and the National Archives and Records Administration. We also thank our colleagues Dr. David Cantor for the extensive historical research he completed on the subject of FDR and the NIH before we initiated our effort to make this film public available, and especially Anatoliy Milihkiker, a contract archives technician in the History of Medicine Division, who recognized the unique content of this film as he undertook a recent survey of the our extensive historical audio-visual collections.

Rebecca C. Warlow is Head of Images and Archives in the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Wednesday, July 5, 2023