70 Years Onward, the NIH Clinical Center Remains a Beacon of Hope

BY VICTORIA TONG, OD

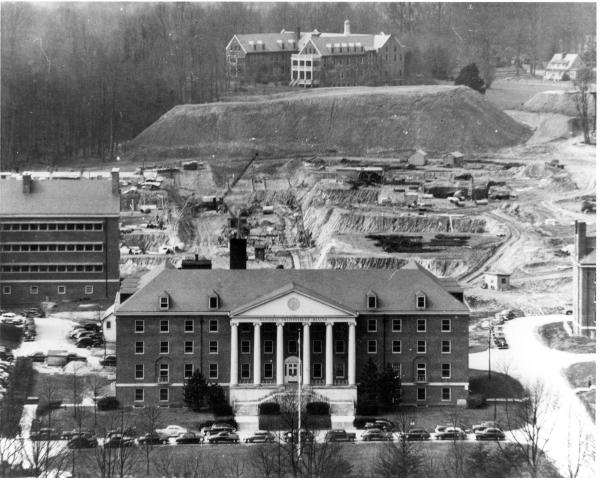

CREDIT: NIH OFFICE OF HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

Construction of the Clinical Center, which was the 10th building constructed at NIH, began in the late 1940s. In this photograph, Building 1 is shown with the beginnings of construction of the Clinical Center behind it.

Standing in front of the towering red brick exterior of Building 10 for the first time can be a daunting experience. Fourteen stories tall at its highest, with more than 10 miles of corridors, occupying more than 3 million square feet, Building 10 is home to the NIH Clinical Center, the world’s largest hospital dedicated solely to clinical research.

Yet even more impressive than the millions of bricks in its structure are the incredible achievements that have taken place within its walls.

Since its opening in July 1953, the Clinical Center has served more than 500,000 patients who have volunteered to participate in clinical research studies. This partnership between patients and scientists has led to countless medical breakthroughs, including the first time a cancerous solid tumor was cured with chemotherapy and the development of the first antiretroviral drug to treat HIV and AIDS.

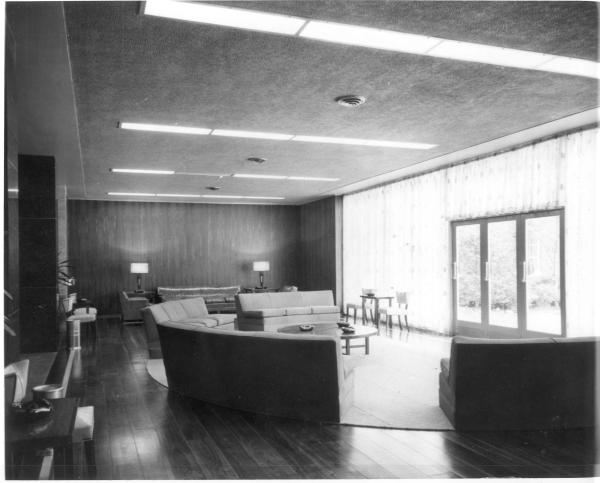

CREDIT: THE OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

The Clinical Center was constructed as a research hospital in which laboratory research and clinical investigations involving patient care were paramount. This photograph shows the Clinical Center entrance lobby in the early years. The Warren Grant Magnuson Clinical Center has grown over the years, adding facilities and centers, and is considered the one of the largest clinical research facilities in the world.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Clinical Center, former NIH Director Francis Collins delivered a Grand Rounds lecture in the Lipsett Amphitheater on June 28. Collins divided his talk into two parts, beginning by presenting many of the medical milestones that have occurred at the Clinical Center before describing his hopes for its future directions.

Collins peppered his talk with examples of the Clinical Center’s recent major advances. Noting the emergence of immunotherapy as a field, he recognized the work carried out by Steven Rosenberg, the Chief of Surgery at the National Cancer Institute. Rosenberg has pioneered several immunotherapy treatments for cancer patients, including a therapy where tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which can recognize and destroy specific tumor cells, are isolated from the patient, grown to large numbers in the lab, and then reinfused into the patient.

Collins also highlighted research done by Senior Investigator John Tisdale and Lasker Scholar Courtney Fitzhugh at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Tisdale and Fitzhugh have explored the use of gene therapy to treat and potentially even cure sickle-cell anemia. In this experimental treatment, a viral vector is used to insert a corrected copy of the sickle-causing gene into bone marrow cells.

CREDIT: NIH OFFICE OF HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

The Clinical Center (Building 10) at NIH was constructed for long-term patients. A reflecting pool was included to urge in-patient use. The nurses accompanied patients and family outside for fresh air and sun. Building 10 was constructed as a research hospital and combines research laboratories with patient care.

Collins mentioned numerous advancements in infectious disease research as well, noting Nancy Sullivan’s leadership in the development of a vaccine for Ebola and the teamwork displayed in the Clinical Center to treat a nurse from Texas who had contracted Ebola in 2014.

The Clinical Center has been home to a multitude of advancements in mental health research. Collins spotlighted the ketamine research conducted by Carlos Zarate, the chief of the Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch at the National Institute of Mental Health. Zarate’s work has demonstrated that ketamine can rapidly reduce symptoms of depression in individuals who have not responded to other treatments.

Then there’s the Clinical Center’s international recognition for studying rare diseases. Sharing his own lab’s experience with researching progeria, a rare form of premature aging, Collins spoke of the importance of natural history studies to investigate the development of a disease over time before moving forward to consider possible therapeutics. The Undiagnosed Diseases Program, founded in 2008 by William Gahl, a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute, has admitted more than 1,500 patients and has since expanded to become the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, with 12 clinical sites nationwide.

CREDIT: NIH OFFICE OF HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

A patient and clinician enjoy the sunlight in the original Clinical Center solarium.

Looking towards the future, Collins presented several areas for progress for the Clinical Center. A common theme was expanding the infrastructure on campus to better support ongoing research, which is already underway with two new cell-processing facilities scheduled to open within the next year and the Roy Blunt Center for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias having opened last September.

Collins was excited by the potential of precision medicine, which involves tailoring prevention and treatment to the individual patient. The NIH All of Us research program has been collecting data from hundreds of thousands of individuals, including their genome sequences and information about their lifestyle and environment, to build a diverse database that future research studies at the Clinical Center can draw upon.

CREDIT: NIH OFFICE OF HISTORY AND STETTEN MUSEUM

This photograph shows the Clinical Center patient waiting area in the early years.

After a whirlwind tour of the Clinical Center’s past accomplishments and future endeavors, Collins expressed his deep appreciation for the privilege of being involved with the Clinical Center. He referred to it as a “House of Hope,” a place where many patients come to as a best hope for treatment after conventional medical care has not come up with the answers, even though there is no guarantee that an experimental protocol will be effective for them.

“The people that we are most grateful to are the patients who have come here and put their trust in us,” Collins said. “They were willing, even if it wasn’t going to help them, to know that we were going to learn something that might help the next person.”

Watch Collins’ talk at https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=49881.

The Magnuson Act’s Continuing Legacy

Warren G. Magnuson, a congressman from the state of Washington, was a dedicated advocate for medical research who, among his legislative accomplishments, co-sponsored a bill in 1937 to create the National Cancer Institute (NCI). In appreciation of his years of support to the NIH, the Clinical Center was renamed the Warren G. Magnuson Clinical Center in 1980, a year before his retirement from the U.S. Senate.

Magnuson also contributed to the NIH more indirectly. Eighty years ago, he proposed the Chinese Exclusion Repeal Act, also known as the Magnuson Act, which allowed Chinese immigrants to enter the United States for the first time since the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which effectively banned immigration from China.

Although the Magnuson Act abolished the outright exclusion of Chinese immigrants, it was more of a symbolic act than a complete liberalization of admitting Chinese people into the country. As prescribed by the nationality-based quota system of the Immigration Act of 1924, just 105 Chinese immigrants were allowed into the country per year.

The Magnuson Act served as a starting point for gradually easing restrictions on Chinese immigrants. Together with subsequent legislation, it nudged open the door for Chinese scientists to train and do research in the United States and at the NIH.

One such scientist was Min Chiu Li, who came to the United States in 1947 and joined the NCI in 1955. Li studied choriocarcinoma, a highly malignant form of cancer that develops in the placenta, and he observed that patients with choriocarcinoma exhibited elevated concentrations of a tumor marker called human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) in their blood.

By treating patients with a chemotherapy drug called methotrexate, to the point that not only their visible tumors disappeared but also the concentration of hCG in their blood normalized, Li and his colleagues were able to send the cancer into complete remission, marking the first cure of a solid tumor using chemotherapy. For his work, Li won a Lasker Award in 1972.

Another trailblazer at the NIH was Jacqueline Whang-Peng. Whang-Peng was born in Jiangsu province, China, earned her medical degree in Taiwan, and joined the NCI in 1960, where she focused on cytogenetics, or the study of chromosomes and their effect on cell behavior. One of her notable discoveries was identifying a specific chromosomal abnormality linked to Burkitt lymphoma, an aggressive cancer of the lymphatic system. In 1971, she received the Arthur S. Flemming Award in recognition of her scientific contributions.

The impact of the Magnuson Act has been generational, paving the way for many Chinese immigrants to work and train at the NIH. The children of earlier generations of immigrants have also joined the NIH community, including Maryland Pao, the clinical director of the National Institute of Mental Health, whose parents came to the United States from China in the mid-1950s. In this way, the legacy of the Magnuson Act lives on through the generations of Chinese immigrants and their children who have continued to make significant contributions to the NIH community.

Victoria Tong, a Pathways editorial intern at The NIH Catalyst, is a sophomore at the University of California at Los Angeles and expects to major in chemistry. She was the editor of the student newspaper at Richard Montgomery High School in Rockville, Maryland. In her free time, she enjoys playing tennis, solving crossword puzzles, and scoping out new restaurants.

This page was last updated on Friday, September 8, 2023