You Are What You Eat

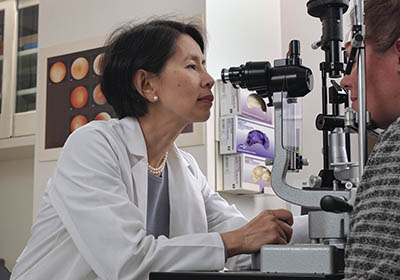

Profile: Emily Chew, M.D.

Emily Chew understands the power of nutrition, and she has the data to back herself up. Eating fish as “brain food” before taking an exam and consuming goji berries to achieve better eyesight were some of the many wisdoms she learned when growing up in a Chinese immigrant family in British Columbia (Canada).

CREDIT: NEI

Emily Chew’s work has furthered the understanding of the influence of nutrition and genetics on blindness especially in slowing the progression of retinal vascular diseases such as age-related macular degeneration.

“All my life I’ve been aware [that] my whole family are foodies,” said Chew, who is a senior investigator at the National Eye Institute (NEI) and director of NEI’s Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications. Her family’s wisdom certainly proved useful. Chew’s 30-year career at the NIH has led to instrumental clinical studies to further our understanding of the influence of nutrition and genetics on blindness, especially in slowing the progression of retinal vascular diseases such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Influential Mentors

Chew’s pursuit of clinical research was inspired by influential mentors throughout her medical training. While at the University of Toronto, where she received her M.D., her mentor was Brenda Gallie, an ophthalmologist whose research focused on retinoblastoma (an eye tumor in children). “She was a wonderful role model,” Chew said. “She impressed upon me how you could do wonderful things clinically, one patient at a time. But to do research you really are affecting and impacting many more people.”

As a fellow at Johns Hopkins’ Wilmer Eye Institute (Baltimore), Chew began her work on macular degeneration. One of her mentors was the late Arnall Patz, who discovered that oxygen therapy could cause blindness in premature infants. Patz was “incredible in the way he looked at life and how he approached patients,” said Chew. “And he is the humblest person you would ever meet.”

As an established research leader, Chew has mentors even now. She talks to leaders throughout the NIH “who have been very kind, considerate, and generous with their time,” she said. “I’ve been very lucky; I think at every stage of your life one needs mentoring.”

Chew has been mentoring clinician–scientists herself for the past 30 years. As the director of the Medical Retina Fellowship program (2002–2017), she mentored some three dozen trainees who have gone on to work in eye-research programs across the United States and elsewhere.

“Right off the bat, [Chew’s] mentee is a new collaborator,” said Wai Wong, who completed a medical retina fellowship in 2007 and is now a senior investigator in NEI. “She allows the opportunity for each person to bring their best ideas to the table, and in that way, people feel inspired about their project and contribute in the best way possible.” Wong has continued to collaborate with his mentor for the past 14 years.

Chew has also mentored medical students in NIH’s Medical Research Scholars Program as well as people in two former programs—the NIH–Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Scholars Program and NIH’s Clinical Research Training Program.

She strives to instill in her mentees the importance of research and to nurture their curiosity, just as her mentors have done for her. She is delighted to see her mentees go on to do great things, pursue their passions, and value the importance of research. “It instills curiosity and allows them to become more in tune with their work,” Chew said. “Having this variety helps all of us; it helps humankind.”

She hopes to inspire future leaders in research to work with integrity above all. In doing so, she’ll have passed on a great deal to them. “You can be brilliant, work hard, but above all, [you need] integrity,” she said. “Unless we inspire these young people do these things it’s easy to lose them.”

Eyes Wide Open

Chew’s approach in each clinical trial is to enter with her eyes wide open and to see what the data tell her. The Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) group, of which she is a member, conducted a randomized clinical trial (AREDS) at 11 centers with 4,757 participants, aged 55–80 years, who had varying degrees of AMD. The trial demonstrated that a high-dose supplementation with vitamins C and E, beta-carotene, and zinc with copper reduced the risk of progressing to late-stage AMD. (Arch Ophthalmol 119:1417–1436, 2001; DOI:10.1001/archopht.119.10.1417)

Based on the AREDS data, the group found that there was a correlation between participants who ate green leafy vegetables and a diet rich in fish with a lower risk of developing AMD. They conducted the AREDS2 study, which involved 82 clinical centers and 4,203 participants, age 50–85, who had bilateral intermediate AMD or advanced AMD in one eye. The AREDS2 study showed that replacing beta-carotene with lutein/zeaxanthin–found in green leafy vegetables–was 20% more beneficial in reducing the progression to advanced AMD, especially in those who ate the least amount of green leafy vegetables; adding omega 3 fatty acids, however, was neither beneficial nor harmful (Ophthalmology 119:2282–2289, 2012).

The Mediterranean diet emphasizes consumption of whole fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, fish, and olive oil, as well as reduced consumption of red meat and alcohol.

More data from both studies have shown the protective effects of the Mediterranean diet—high in vegetables, whole grains, fish, and olive oil—and the importance of fish consumption in AMD rather than just the intake of supplements. “It’s a synergy of a number of things,” Chew said.

In an April 2020 article published in Alzheimer’s and Dementia: the Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, Chew and her group reported that a recent analysis of data from the AREDS and AREDS2 studies showed that adherence to the Mediterranean diet correlates with higher cognitive function and that dietary factors also seem to play a role in slowing cognitive decline. (Alzheimers Dement, 2020; DOI:10.1002/alz.12077)

Genetic Studies

In 2005, Chew’s group conducted the first genome-wide association study done in the eyes. They identified the role of complement factor H (CFH) polymorphism as a genetic risk factor in the progression of AMD. The group noted a sevenfold risk of late AMD with the presence of CFH. This discovery and three other simultaneous studies with different methodologies came to the same conclusion. “It was a turning point in the field of AMD research [and] a banner year for AMD genetics.” Chew notes that this discovery led to the exponential increase in genetic studies in AMD, increasing our knowledge of genetic pathways drastically. (Science 308:385–389, 2005; DOI:10.1126/science.1109557)

Chew has since collaborated with many groups around the world to put the data together, showing genetic markers, and finding indicators of genetic pathways important for AMD. “With each accomplishment comes more challenges and new questions,” she said. That’s good because “We’re never out of a job.” She smiled.

CREDIT: NATIONAL EYE INSTITUTE

Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A fundus photo (ocular documentation that records the appearance of the retina) showing geographic atrophy (the larger fuzzy circle) associated with intermediate macular degeneration. The small bright circle is the optic disk or optic nerve head.

Chew’s current work focuses on the earlier stages of macular degeneration, and she seeks to alter the natural course of disease progression. “If we can change the progression to the more intermediate late-stage AMD,” her group would have done a great service to patients, she said. A 10–15% improvement in vision in the early stages of AMD can be monumental to patients’ sight and in turn improve the quality of life. “It’s quite clear that at every stage of macular degeneration you can make an impact [on] its progression through diet in some way,” she said.

Artificial Intelligence

Looking forward, the Chew lab is embracing the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning on the detection and progression of AMD, coupled with further advancements in genetics and long-established clinical-trial principles. Her team has shown that deep-learning methods can help physicians make more accurate predictions of the progression and risks of developing the later form of AMD. Chew is taking advantage of the technology evolution to enroll patients and even to predict what’s going to happen in the study. “I think AI is going to be phenomenal for clinical research and for actual clinical care,” she said. That “makes me very excited.”

Better treatments

Her group’s work over the past three decades has resulted in dramatic changes in treatment for AMD. Treatments for blindness disorders range from injecting into the eye anti-angiogenic drugs that inhibit the growth of new blood vessels that can cause blindness; to using a hot laser to seal retinal blood vessels that are leaking in the wet form of AMD (but doing so can also accidentally destroy blood vessels and neighboring tissue); to implanting tiny telescopes in the eye to improve central vision. But Chew’s research shows that making simple nutritional shifts in the diet can have a strong positive impact.

When speaking about her career in the NIH intramural program, Chew says that she “kind of grew up here.” She values the collaborative atmosphere, especially among different research disciplines, but also among clinicians and basic scientists. “The beauty of NIH is that we have many wonderful colleagues who are very collaborative with similar goals,” she said. She appreciates the ever-changing research environment in which there is always something new to learn.

Emily Chew gave the Astute Clinician Lecture as part of the NIH director’s Wednesday Afternoon Lecture Series on December 11, 2019. To watch a videocast of her lecture, entitled “We Are What We Eat: Nutrition, Genes, Cognition and Deep Learning in Age-related Macular Degeneration,” go to https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=35115.

EMILY CHEW, M.D.

Senior Investigator and Director, Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, National Eye Institute (NEI); Deputy Clinical Director, NEI

Education: M.D. from the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine (Toronto, Ontario, Canada)

Training: Residency in internal medicine and ophthalmology, University of Toronto (1977–1981); Fellowships in Medical Retina and Genetics (1982–1983), Wilmer Eye Institute, Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore), and Nijmegen University (now Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands).

Before coming to NIH: Assistant professor, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Toronto

Came to NIH: In 1987

Website: https://irp.nih.gov/pi/emily-chew

This page was last updated on Thursday, March 24, 2022