Is Music Really the Medicine of the Soul?

An Interview with Renée Fleming and Francis Collins

J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture

What happens when you get a world-renowned scientist and a famous opera singer in the same room? A spontaneous rendition of “The Times They Are a-Changin’” and the establishment of an important collaboration. NIH Director Francis Collins and Renée Fleming, who met a few years ago at a dinner party, realized that they both were curious about how music affects our minds. And so the “Sound Health: Music and the Mind” initiative, an NIH–Kennedy Center partnership in association with the National Endowment for the Arts, was born.

CREDIT: CHIA CHI (“CHARLIE”) CHANG

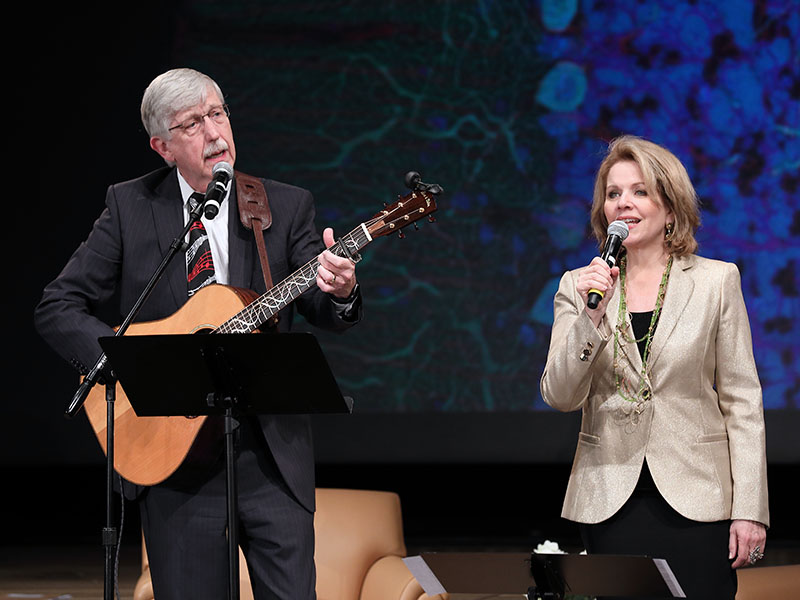

Opera singer Renée Fleming visited NIH in May as the featured guest at the annual J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture. She talked about the Sound Health initiative, an NIH–Kennedy Center partnership in association with the National Endowment for the Arts, and had an on-stage conversation with NIH Director Francis Collins. Afterwards she and Collins sang Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and the spiritual song “How Can I Keep from Singing?”

Fleming visited NIH on May 13, 2019, as the featured guest at the annual J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture, named for the former deputy director for intramural research. She and Collins discussed the creative process, the intersection of music and science, and the Sound Health initiative, which aims to expand our understanding of the connections between music and wellness.

Music has been part of our lives for millennia and may well predate speech. The earliest known surviving instrument is a bone flute from about 40,000 years ago, and our vocal mechanisms have hardly changed throughout the years. “Can you imagine a Neanderthal opera?” Fleming joked. Because music has been part of our society for so long, it follows that it must have an identifiable impact. Indeed, it has been shown that exposing children to music can enhance reading proficiency and tends to lead to higher rates of career success.

Plato remarked that “Music is the medicine of the soul.” But why is it so beneficial? We can all understand how a piece of music can influence our emotions, but one study showed that rhythm may also be important in our development. Fleming showed a video of a study that demonstrated that when a stranger bounced in time with a baby, the infant was more likely to help the stranger complete a task afterwards than if the bouncing was out of sync. This study showed that even from an early age, music can bring us together, but to find out what happens in the brain, we need to be able to observe neuronal activity.

Bring in the magnetic-resolution-imaging (MRI) scanner. In 2017, Fleming experienced the feeling of being in such a scanner for herself. She chose the song “The Water Is Wide,” and her brain activity was measured as she spoke, sang, and imagined singing the words. Interestingly, imagining the words produced the most striking brain activity, but she put this down to the fact that singing is natural to her; imagining the words was the hardest.

MRI studies have revealed the fascinating influence of music. Fleming described an experiment in which neuroscientist Charles Limb asked jazz piano prodigy Matthew Whitaker to undergo two tasks while in the scanner. First, Whitaker had to listen to a boring lecture and, unsurprisingly, very few areas of his brain showed activity. However, when he listened to his favorite band, his brain lit up like a Christmas tree. Although Whitaker is blind, even his visual cortex responded, indicating that music could have very potent therapeutic benefits.

One striking example, said Fleming, is the case of Forrest Allen, who was left in an almost lifeless state after a snowboarding accident in 2011 that caused a traumatic brain injury. Allen’s recovery was long and tough, surgeries to repair his skull catapulted him into comas, and he couldn’t speak for two years. His childhood music teacher noticed a tiny movement in Allen’s pinkie finger when music was playing, as if he was tapping along with the rhythm. As part of Allen’s rehab, the music teacher began using rhythm and melody to help his brain heal. Thanks to his doctors, surgeons, and physical therapists, Allen slowly recovered. Thanks to music therapy, he eventually learned to talk again. Today, Allen is a college student at George Mason University (Fairfax, Virginia).

Given that music can affect us to such a degree, Collins asked Fleming how she manages singing professionally during emotional moments. She recollected two particularly emotional moments—singing “Danny Boy” at Senator John McCain’s funeral in Washington, D.C., in 2018, and performing “Amazing Grace” at the National September 11 Memorial in New York City in 2013. She said that it was all about mental preparation before the events. She had to keep reminding herself that the she was singing for everyone else and not just for herself: The singing had to be right. Despite being raised in a musical family, it was not an easy road to becoming a famous singer. Nevertheless, she had the drive to be successful and became fascinated by the skill and practice of singing, observing that “The voice is like a horse: You never know when it will betray you and be off!”

Regarding her dreams for the Sound Health program, she hopes music therapy will become more widely covered by insurance and that the arts will be increasingly involved in our general well-being. She concluded by saying that she had been privileged to work with so many amazing people and takes great delight in performing in all sorts of ways. At this, Collins picked up his guitar and they wrapped up this unique event in an unforgettable way. They joined their voices in harmony to Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” and the spiritual song “How Can I Keep from Singing?” The audience sat spellbound as the music echoed around the room.

CREDIT: CHIA CHI (“CHARLIE”) CHANG

The writer, Joanna Cross, got to meet Renée Fleming.

To view a videocast of the May 13 Rall Lecture featuring Renée Fleming (NIH only), go to https://videocast.nih.gov/launch.asp?27524. To see a video of Collins and Fleming singing together, go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=23&v=RpuQ65ESq4c.

This page was last updated on Monday, April 4, 2022