Historical Medical Films at the National Library of Medicine

How a Unique Collection Started and Grew

CREDIT: MOHOR SENGUPTA, NEI

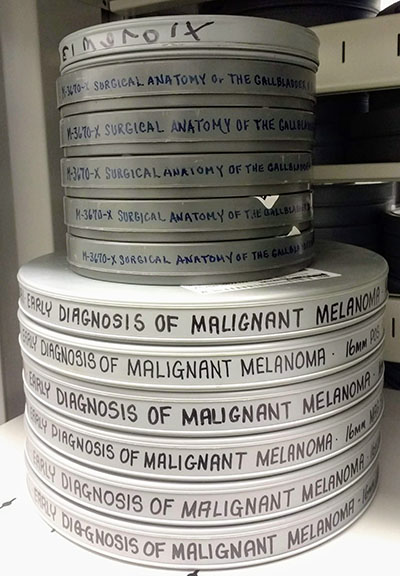

The National Library of Medicine (NLM) has one of the world’s largest collections of medical films and videos. Shown: Several 35-mm films at NLM’s storage vault in Bethesda.

One of the world’s largest collections of medical films and videos is at the National Library of Medicine (NLM), which has been collecting and preserving them—and making them available to researchers—since the 1950s. Then-NLM-Director Colonel Frank Bradway Rogers set up a system to include audiovisuals as part of the NLM’s congressionally mandated mission to acquire a wide variety of materials pertinent to medicine. He hoped that such a repository would be a go-to place for visual information on aspects of medicine ranging from delivering an infant to how to treat battle wounds in the field. By 1962, NLM had acquired almost 700 titles (each title could have several associated items). Today the collection comprises nearly 40,000 titles and an estimated 8,000 catalogued film and video recordings considered historically significant. Some items are so rare that NLM has the only surviving copy.

In February 2019, NLM launched a new website—“Medicine on Screen: Films and Essays from NLM”—a curated, freely accessible portal presenting digitized historical titles from its audiovisuals collection.

Because many of the films that NLM acquired in the 1950s featured medical training and clinical procedures, Rogers realized that it would be more appropriate to house them in the audiovisual branch within the Communicable Disease Center (now the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC) in Atlanta. Thus, the collection resided there from 1962 through the early 1980s.

This period saw a large addition of films to the initial collection. During this time, the National Medical Audiovisual Center (NMAC) was established in Atlanta and its mandate was to produce public-health, clinical, training, and other medical films on behalf of the United States government. NMAC, which started as a branch of CDC’s predecessor—the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas—in the 1940s, was integrated into NLM in 1967 and was physically moved from Atlanta to NLM’s Bethesda campus in the 1980s.

At first, the film collection was managed by NLM’s General Collection, which started loaning some of the 16-mm films to patrons. In 1988, all films that predated 1970 were transferred to NLM’s History of Medicine Division (HMD), which also accepted transfers and donations from other sources. Today, HMD holds a wide variety of material in audiovisual format including educational and instructional titles, animations, documentaries, and films of live surgeries and counseling sessions. The films provide a peek into medical knowledge and practices of a bygone time. There are thousands of post-1970 titles in the collection as well. The audiovisual materials at NLM, whether housed in HMD or in the General Collection, are considered as one collection, now numbering about 40,000 titles.

Where did the films come from?

Many of the titles in the collection were transferred to NLM from other government agencies. Advocacy organizations such as the American Dental Association (ADA) or hospitals including the former Western Psychiatric Institute in Pittsburgh also have contributed large numbers. Besides NMAC (which transferred about 1,600 films), all branches of the military and other government agencies have given films to NLM, as have other NIH institutes such as the National Institute for Mental Health. The Office of NIH History often coordinates NIH-related film transfers to NLM.

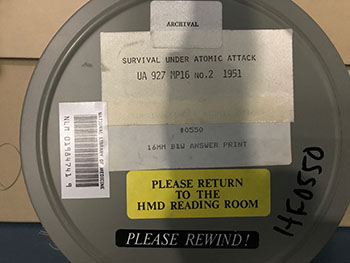

PHOTO CREDIT: SARAH EILERS, NLM

This film, Surviving Under Atomic Attack, was made during early years of the Cold War.

In the 1940s, making medical documentaries and short films related to the battlefield was common. These films were intended to inform soldiers and citizens about such health hazards as malaria, dysentery, and yellow fever. Films on psychiatric illnesses, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (then called shell shock or combat fatigue), were declassified before being donated to NLM. And, as the Cold War (1947–1991) intensified in the 1950s, the military produced dozens of films about public preparation and response to nuclear attack.

Donations also came from state health authorities including New York State’s Department of Health and the State Psychiatric Institute, hospitals, and academic institutions. Among the films donated were several collections on psychiatric problems and their societal implications. Medical and advocacy organizations such as the ADA mentioned above, the American Cancer Society, and the National Tuberculosis Association donated films that typically had been produced for circulation in schools and community organizations.

A still from a 1938 film titled Three Countries Against Syphilis, which was produced by the U.S. Public Health Service and donated to NLM by Leroy E. Burney.

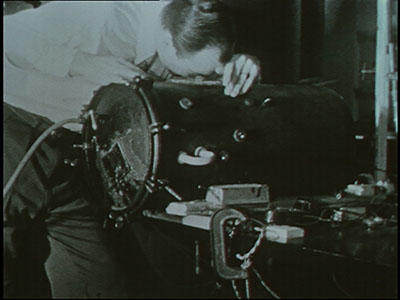

Pharmaceutical, surgical-equipment, and medical-device companies donated more than 1,000 films. Films made by doctors and scientists are in the collection, too. For example, NLM holds a set of World War II–era films on wound ballistics and decompression research made by Princeton physiologist Edmund Newton Harvey (1887–1959), who studied decompression sickness and tissue damage caused by high-velocity missiles.

NLM holds a set of World War II–era films on wound ballistics and decompression research made by Princeton physiologist Edmund Newton Harvey, who studied decompression sickness and tissue damage caused by high-velocity missiles. Shown: Screen capture from Harvey’s 1949 silent film Decompression Sickness Project, in which he is peering into a decompression chamber in his lab.

Donations also come from the unlikeliest of places. One set of films on childbirth education was discovered in a dumpster in Jacksonville, Florida, 15 years ago and donated to NLM in 2016.

The History of Medicine’s most recent acquisition came in February 2019. Grafton County Senior Services, a small organization in New Hampshire, donated about 30 VHS tapes and audiocassettes on dementia, Alzheimer disease, and elder-care.

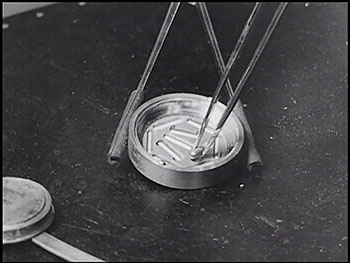

A still from a 1940 film titled Choose to Live, which is about early detection of and treatment for cancer. Depicted here are radium tubes used for cancer treatment. The film was produced by the U.S. Public Health Service and donated to NLM by former U.S. Surgeon General Thomas Parran Jr., who served from 1936 to 1948.

Availability of the films

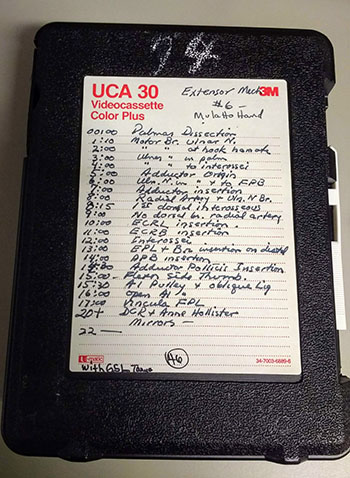

The films arrive at NLM in formats ranging from perishable U-matic tapes (common in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s) to the more stable 16-mm and 35-mm formats (used in documentary and feature films respectively). The original films and tapes are in cold storage and out of circulation, but DVD viewing copies are available for thousands of titles, and about 350 films are available for viewing in NLM Digital Collections. The NLM website “Medicine on Screen” takes viewers deep into selected rare films, with essays that provide context and commentary. All cataloged titles can be found via LocatorPlus, the NLM public-access catalog.

Some of the collection is stored onsite in a basement vault at NLM. Sarah Eilers, NLM’s Historical Audiovisuals Program Manager, showed this writer around the vault, where hundreds of titles in various formats (U-matic tapes, Betacam SP formats, 16-mm and 35-mm films, and VHS tapes) are stored. Eilers and her colleagues at NLM are preserving and digitizing these rare and unique historical formats to protect them from the ravages of time.

CREDIT: MOHOR SENGUPTA, NEI

U-matic tape at the NLM vault in Bethesda.

About 80 percent of the collection is stored offsite in two vaults that NLM leases at the Iron Mountain facility, a former limestone mine in western Pennsylvania. A “cool vault” stores magnetic tapes and microfilms at 55 degrees Fahrenheit and a “cold vault” stores films at 35 degrees Fahrenheit. Underground at the facility, temperature and humidity are ideal for long-term film storage. The Internal Revenue Service and Warner Brothers Pictures are some of the other corporations leasing space at Iron Mountain. Newly acquired films are shipped to the facility and wait their turn to be processed at the Bethesda campus. On the other end, older films requested by documentary producers for high-resolution copies are recalled from the facility to be digitized and shared.

CREDIT: SARAH EILERS, NLM

About 80 percent of the NLM’s historic film collection is stored offsite in two vaults that NLM leases at the Iron Mountain facility, a former limestone mine in western Pennsylvania.

Managing the historical audiovisuals collection at NLM

“I’m responsible for intellectual and physical control of the collection,” Eilers said. New material arrives regularly, and, to make it valuable and available for research, staffers must assess, inventory, and store the items, then catalog and digitize them as resources permit. About five percent of the collection has been digitized so far. The sound quality of older films can be poor, making it harder for them to be transcribed and subtitles added. Older films also have outdated medical terms that may be unfamiliar to the transcriber or viewer. “We don’t change them,” Eilers noted. “We just capture exactly what’s being said.”

NLM often gets requests for digital copies from individual patrons and documentary-film makers. For example, the production company that made the Ken Burns film Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies, adapted from the Pulitzer prize–winning book by Siddhartha Mukherjee, used three films from NLM’s collection. The company arranged—and paid—to have the films digitized by a vendor used by NLM; NLM provided the original films to the vendor.

CREDIT: NLM

Sarah Eilers is NLM’s Historical Audiovisuals Program Manager.

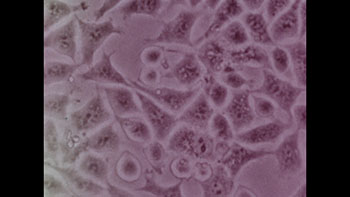

A still from the 1968 film produced by National Educational Television and Radio Center and titled Drugs Against Cancer. This was one of the three films in the NLM collection used in the making of Cancer: The Emperor of All Maladies.

Eilers, along with project consultant Oliver Gaycken of the University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland), is responsible for decisions about which titles appear in “Medicine on Screen.” Rarity or uniqueness of a film and patron demand are factored into the selection process. “Medicine on Screen” highlights selected films from the NLM’s audiovisual collections along with expert commentary that sets the films in historical context. The essays explore “the social, cultural, and medical milieu of the work, as well as cinematic techniques, the agendas of directors or producers, and other contextual details,” according to the website (https://medicineonscreen.nlm.nih.gov). Eilers is formalizing procedures for identifying potential contributors, guidelines for essayists, planning online-publication dates, and acquiring author permissions.

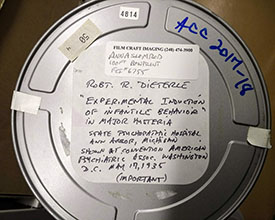

Finally, acquiring new titles is an ongoing task for the historical film curator. In one case, she tracked down and met with a family member of renowned psychiatrist Robert R. Dieterle (1896–1969) and secured the Dieterle-produced film titled Experimental Induction of Infantile Behavior in Major Hysteria. That film, along with a paper of the same name, was presented at a convention of the American Psychiatric Association in Washington, D.C., in 1935.

CREDIT: MOHOR SENGUPTA, NEI

Acquiring films for the NLM historical film collection can include meeting with family members of the films’ creators. NLM staff met with a family member of renowned psychiatrist Robert R. Dieterle and secured his film titled Experimental Induction of Infantile Behavior in Major Hysteria.

Eilers is also interested in constructing education and outreach programs for high-school and college students in order to promote films as one of the primary sources of information in educational settings.

Frank Rogers would be proud to see how the collection has grown and that it spans more than a century. More than 900 titles date from before 1950. The oldest film in the collection is a 1917 film showing a step-by-step procedure for performing a root-canal technique. Ouch!

To read more about the films and essays in NLM’s collection, click here.

This page was last updated on Monday, April 4, 2022