Dieting May Disrupt Women’s Sleep

IRP Study Reveals Influence of Calorie Intake and Reproductive Cycle on Sleep

New IRP research finds that non-obese women get less sleep during certain times in their menstrual cycles and that cutting calories exacerbates the problem.

Doctors have long emphasized the importance of maintaining a healthy body weight and getting enough sleep, but in our time-limited lives, we often have to choose between spending time exercising, preparing healthy meals, and getting sufficient shuteye. And the number of hours in the day may not be the only thing that pits weight loss against sleep. A recent IRP study suggests that young women who are not obese get poorer sleep when they change their diets in order to lose weight.1

Many studies of weight loss have understandably focused on individuals with obesity, since their excess body weight increases risk for a whole host of health problems. Such studies typically show that weight loss improves sleep, likely due to alleviating a condition called obstructive sleep apnea that disrupts breathing when people fall asleep. However, many women who aren’t overweight to begin with want to lose a few pounds, and it’s not clear how their weight loss efforts affect their sleep.

“If you disrupt sleep, that has a whole host of downstream consequences that can add stress to people’s lives and compromise their daily functioning, and in those individuals who are trying to lose weight, it could reduce their ability to achieve their goals,” explains Skand Shekhar, M.D., M.H.Sc., the new study’s co-first author and an associate research physician in the lab of IRP senior investigator Janet Hall, M.D, M.S., the study’s senior author. “It can also exacerbate all those mental health and stress-related problems that we’re seeing increasingly reported now. Ask any sleep-deprived person how it affects their stress levels — they would know. I tell you this with first-hand experience.”

Dr. Janet Hall, the study’s senior author (left), and Dr. Skand Shekhar, the study’s co-first author (right)

Moreover, calorie intake is not the only thing that can affect sleep in women. Many studies have reported that women get less restful sleep during certain times in their menstrual cycle, but so far, most research has relied on participants’ own subjective reports about their sleep or measured sleep in a clinic. Consequently, Dr. Shekhar and Dr. Hall wanted to use more precise, objective measures to assess how the menstrual cycle affects sleep in women who are going about their everyday lives.

“All of this was done in normal settings rather than having volunteers come to a clinical setting, which can disrupt sleep itself,” Dr. Shekhar says. “We did this in people’s own routine, everyday environment, so this study is more generalizable than inpatient or hospital studies.”

In the new study, the IRP researchers measured participants’ physical activity and sleep by having them wear movement trackers on their wrists, and they also tracked the women’s menstrual cycles using daily hormone measurements. In addition, the study included a dietary component, examining how the volunteers slept in the month following five days eating a diet containing enough calories to maintain their body weight compared to in the month after five days eating a reduced-calorie diet. Dr. Hall and Dr. Shekhar didn’t really expect the lower-calorie to have much of an effect though — which is why they were surprised when they crunched the numbers.

Contrary to the researchers’ predictions, in the month following the reduced-calorie diet, the volunteers woke up more often from sleep and were awake longer each time compared to the month after the weight-maintenance diet. The women experienced the greatest disruption in their sleep in the days leading up to their period, which was roughly 20 days after the end of each five-day diet, and this effect was more pronounced after the reduced-calorie diet.

“We didn’t expect sleep to be disrupted by diet — we just wanted to nail down how the menstrual cycle influences sleep — so that was pretty incredible,” Dr. Hall says. “We were more interested in using the movement trackers to look at activity levels, but it was an opportunity to look at sleep too, and lo and behold, we found that diet affected that.”

"After each diet ended, the women could eat whatever they wanted, so the fact that sleep disruption continued for that long was really mind-blowing,” Dr. Shekhar adds.

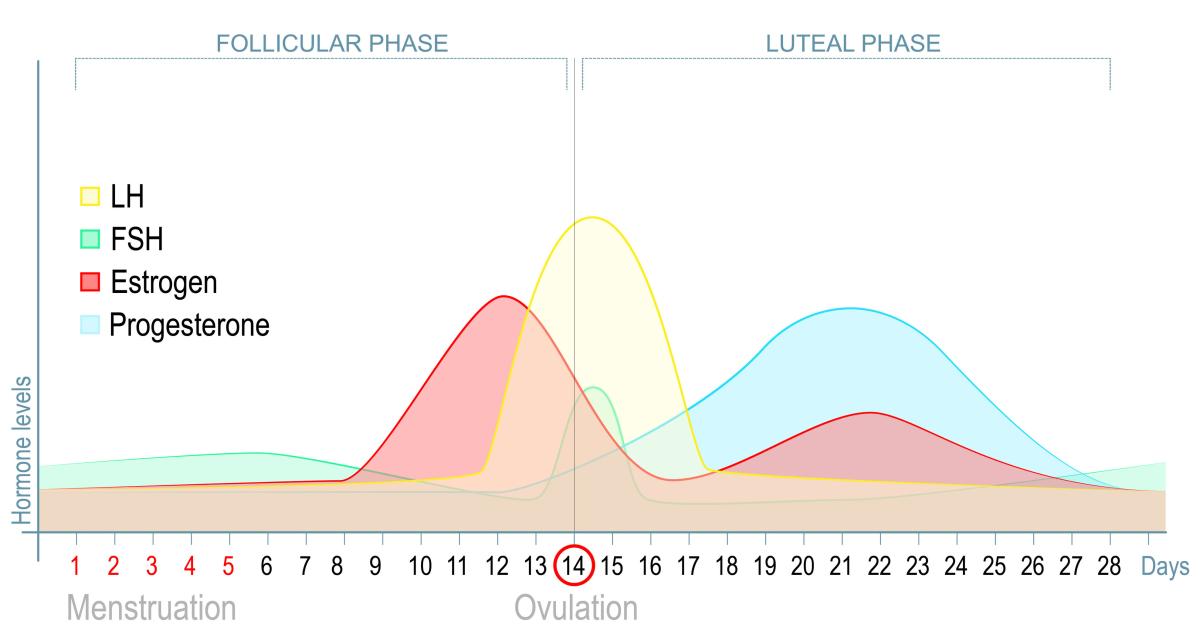

Measuring daily levels of hormones like estrogen and progesterone allowed the IRP researchers to pin down when in the volunteers’ menstrual cycles their sleep was most disrupted, which turned out to be late in the luteal phase.

In addition to the information provided by the participants’ reproductive hormones, the researchers gained more insight into why cutting calories might affect sleep by measuring other hormones as well. They found that when the women had higher levels of orexin-A, a hormone involved in both hunger and sleep, they had poorer sleep than when their orexin-A levels were lower.

“It makes evolutionary sense that if cavemen didn’t have sufficient calories to fuel themselves, they would go foraging and hunting for food so their energy needs were met, rather than spending as much time asleep,” Dr. Shekhar says.

Research on the relationships between the menstrual cycle, food intake, and sleep can help doctors guide patients having sleep difficulties.

As we learn more about hormones like orexin-A that are involved in both hunger and sleep, it may be possible in the future to develop drugs or non-pharmacological strategies that help people on reduced-calorie diets sleep. However, we already know many things people can do to improve their sleep, and scientific research into how food intake and the menstrual cycle affect sleep can influence the advice doctors give to women who are dieting.

“If you understand it, you don’t necessarily need a drug to fix things,” Dr. Hall says. “You just need to tell people the ways to maximize their sleep if they’re in a situation where it’s not as good as it was. It’s not rocket science, but you need to understand whether someone’s sleep might be disrupted before you go through all that trouble. Being able to let people know they can expect this when they diet and there are things they can do to maximize their sleep — that would be really helpful to them.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

References:

[1] Kim AE, Shekhar S, Hirsch KR, Purse BP, McGrath JA, Zava TT, Smith-Ryan AE, Hall JE. Caloric Restriction, the Menstrual Cycle and Sleep in Women without Obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2025 Mar 5:dgaf145. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaf145.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, May 13, 2025