The Life-Saving NIH Blood Bank

Blood Donors Play Critical Role in IRP’s Mission

Hal Wilkins (left) and Dr. Kamille West-Mitchell (right) are part of a dedicated team of staff members at the NIH Blood Bank who work tirelessly to ensure that the NIH Clinical Center has enough blood for its hundreds of patients.

The NIH IRP is full of vampires. Hundreds of patients at the NIH Clinical Center — not to mention scientists in roughly 200 IRP labs — depend on blood provided by NIH’s very own blood bank.

Conveniently located in the NIH Clinical Center, the NIH Blood Bank collects roughly 4,000 units of ‘whole blood’ each year — the process most people think of when they think of donating blood. It also receives more than 2,000 annual donations of specific blood components, which are collected via a process that separates them from other parts of the blood and returns the rest to the donor’s body. Most of those donations gather blood-clotting platelets, but the NIH Blood Bank also occasionally collects oxygen-carrying red blood cells and infection-fighting ‘convalescent plasma.’

A small portion of that blood comes from paid research donors whose blood is used for experiments in IRP labs, but most of it — roughly 85 percent — comes from uncompensated donors and is given to patients at the NIH Clinical Center. For instance, all surgical procedures have a risk of bleeding, so the NIH Blood Bank works tirelessly to ensure it has enough blood of all types on hand to contend with any scenario. In rare, extreme cases, a single surgery can nearly wipe out the NIH Blood Bank’s supply of a particular blood type in the span of a few hours.

“Either the nature of the surgery is complex or just something unexpected happens,” explains Kamille West-Mitchell, M.D., who oversees the NIH Blood Bank as part of her role leading the Blood Services Section in the NIH Clinical Center’s Department of Transfusion Medicine (DTM). “Many of the patients that are coming here to NIH are those difficult cases that other centers won’t operate on. That inherent complexity is part of the challenge of the work done at NIH — work that may not be possible to do elsewhere.”

Kristen Bogacki donated blood for the first time in her life at the NIH Blood Bank in April 2022.

Blood transfusions can also serve as a therapy on their own rather than a supporting player in another procedure. Patients with cancers or other illnesses that affect their blood, such as leukemia or sickle cell disease, require blood transfusions because their own blood cells don’t function properly or they can’t produce enough blood cells on their own. In addition, the bone marrow and stem cell transplants used to treat some types of blood cancer require first destroying patients’ own blood-producing cells and then waiting several weeks for the treatment to take effect.

“Some of those patients are transfused three times a day,” Dr. West-Mitchell says. “You produce trillions of blood cells each day, and if you’ve taken medication to wipe out your own bone marrow and you’re waiting for your donor’s marrow to kick in, your ability to make your own blood cells is significantly hampered if not totally obliterated, so you need transfusions until you can make your own cells independently.”

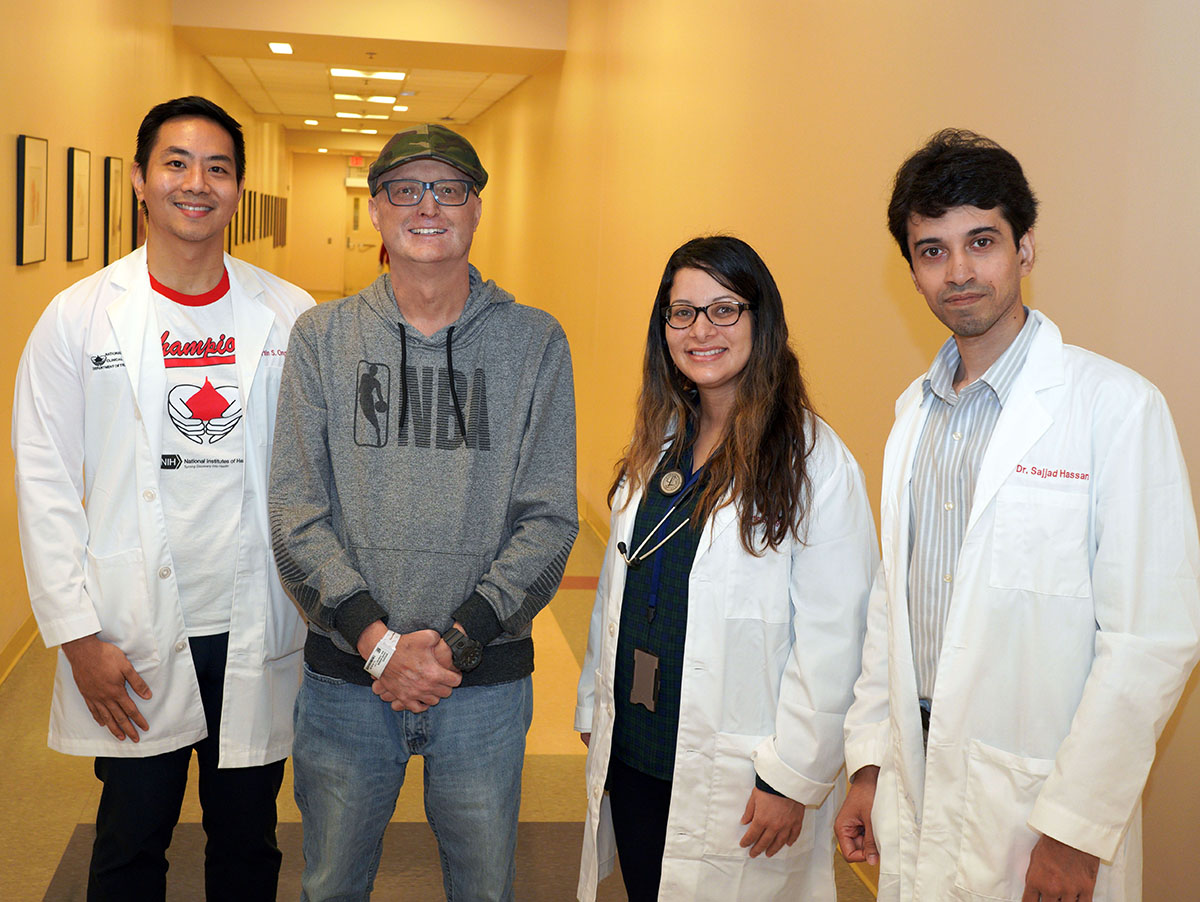

A patient named Aaron (second from left) poses with a group of clinical fellows from NIH’s Department of Transfusion Medicine. Aaron received over 150 transfusions of blood and platelets from the NIH Blood Bank while being treated for a rare disease that weakened his immune system.

Unsurprisingly, relying on the kindness of unpaid donors to provide blood for the Clinical Center’s patients can be a fickle endeavor. When the NIH Blood Bank can’t collect enough blood on its own, it asks for help from other hospitals and institutions that collect blood. When all else fails, the NIH Blood Bank must buy blood from non-profit blood centers.

Even with all sorts of organizations working together to maintain an adequate blood supply, keeping shelves stocked isn’t easy at any blood bank, including NIH’s. While roughly a third of people living in the United States are eligible to donate blood based on the criteria set by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), only about three percent do. This disparity is due to an array of factors, from fear of needles and possible post-donation effects like fainting to the time and inconvenience required to donate to the lack of compensation for most blood donors in the U.S. Dr. West-Mitchell adds that she often encounters people who have never even thought about the possibility of giving blood.

“I don’t think it’s that people know there’s a need but don’t want to help,” Dr. West-Mitchell says. “I’ll sometimes give media interviews about blood shortages and the interviewer will ask me what I’m doing about the blood shortage. If I ask the interviewer if they have ever donated blood, the response is a stunned pause and a ‘What?’ It’s as if they don’t realize people have to donate blood for there to be blood in blood banks. This person is asking me about the problem and still hasn’t thought about it.”

Steven Bailey (center), chief of high-performance computing at the NIH Center for Information Technology, received a plaque commemorating his 100th blood donation at the NIH Blood Bank on May 23, 2022. Here, he poses with DTM clinical fellow Dr. James Long (left) and donor recruitment supervisor Hal Wilkens (right).

Perhaps one fun way to drum up more blood donations might be to show people the 2017 Discovery Channel documentary First in Human, which leaves no doubt about how critical the NIH Blood Bank is to the IRP’s mission. Dr. West-Mitchell remembers when the series’ producers were deciding which of the hundreds of patients at the NIH Clinical Center to focus on in their three-part series.

“They identified three different patients with very different backgrounds and diseases,” Dr. West-Mitchell recalls. "Can you guess what they all had in common? Every single one of them got blood or cells or both from the NIH Blood Bank. Every single one.”

Before that can happen, though, other branches of the NIH Department of Transfusion Medicine must prepare the blood or cellular therapies derived from it for transfusion. Check back soon to learn how DTM’s Laboratory Services Section and Center for Cellular Engineering support the cutting-edge medical treatment and scientific research performed at NIH.

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs in the NIH Intramural Research Program.

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Tuesday, August 15, 2023