Microbes Within Us: A Chat With Science Writer Ed Yong

The human body contains trillions of microorganisms, making every individual his or her own unique ecosystem.

Research into the collection of microorganisms that live in and on our bodies — known as the microbiome — has dramatically expanded in recent years. In fact, the field is one of 12 domains designated as top long-term IRP research priorities. Since the establishment of the NIH’s Human Microbiome Project in 2007, investment in microbiome research across the IRP has increased over forty-fold and now occurs in dozens of labs across more than 20 institutes and centers.

As part of the NIH’s second annual “Big Read,” NIH staff were invited to read and get together to talk about journalist Ed Yong’s 2016 book on the microbiome, I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life. On June 5, to mark the conclusion of this year’s Big Read, Yong visited the NIH campus to participate in a discussion with NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins and answer questions submitted by NIH staff. Read on for some highlights of the event, including what drove Yong to write about our overlooked microbial partners, his thoughts on the applications of microbiome research, and his tips for how scientists can better inform the public about their work.

Yong’s motivation for writing the book

“I did want people to shift their understanding of themselves. I wanted to show them that the world is more complex than they think and that microbes are not just things to go ‘ew’ over or to fear. They’re not just things that are going to make you sick. They are the dominant form of life on this planet. They’ve been around for the longest time and they are really important to all of us. I think that shift in perspective is just gold dust for a writer and, I hope, for a reader too.”

Origins of his interest in the microbiome

“Microbes are fascinating to me. They’re sort of natural underdogs. They’ve been feared and reviled for a very long time, and we’re starting now to understand just how important they are and how fundamental to other, more familiar forms of life they are. And that idea of taking something that is hidden and unseen and that often triggers feelings of fear and disgust and making it something that actually is compelling and interesting is, I think, a very interesting challenge and the fodder for a lot of narrative goodness.”

The structure of his book

“The book is structured around themes, so every chapter deals with a particular aspect of the relationship between microbes and their hosts…When you’re writing at any length, but especially when you’re writing a book, the thing that matters is having a kind of dynamism in the structure, and by that I mean you want to go from broad to detailed, from concrete to abstract…If we think about music, if music always has the same tone and pitch, it just gets boring, so music comes with phrasing — you vary volume and pitch and you go fast and slow, and writing is much the same…To play around with matters of space and time, with detail and concept, I think gives a piece of writing the same kind of dynamism you would get with a piece of music.”

How he chose what to include in the book

“A book can’t be a review of a field, and so [the book] is broad, but it is not comprehensive, and I specifically gravitated towards things that I thought would provide really good stories — so just people doing interesting things, coming across surprises and challenges and mysteries and successes and failures, all of the stuff that all of you encounter in your scientific lives all the time, but are often missing from the scientific literature that we read, the stuff that’s not in PubMed or academic papers. Those tales of discovery were things that I think really tap into these fundamentals of storytelling but are universal to all of the work that we consume, whether it’s a novel or a good nonfiction book…And I was also looking for stories and case studies which would illuminate some of these broader themes about how the microbiome works: how we might go about manipulating it, how it develops over time, the very often tenuous relationships that hosts have with their microbes and how those can swing in different directions or be controlled. With a subject that changes so often, as the microbiome does, I thought that going for those core themes, I would be able to create something that would stand the test of time even as new papers and discoveries were continually being published.”

The potential of probiotics to improve health

“Probiotics have a lot of hype and excitement around them, but by and large they’re a little medically underwhelming. The bacteria in these products were chosen largely for historical reasons — because they were easy to grow and package and manufacture —and not because they were actually well-suited to life in the human body…Microbiologists have said that taking probiotics is a little bit like raising a small number of captive zoo-born animals and releasing them into the jungle and hoping they’ll do well.”

Science journalist Ed Yong

Proven examples of beneficial microbiome-based therapies

“There’s not a lot. I think fecal transplants would be at the top of that very, very short list, perhaps the only thing on that list. This is the idea that if you give people stool from healthy donors, you can transplant it into people who are sick and they will get better. This has only really been well-established for Clostridium difficile infections, but I think the evidence is strong…But even for C. diff infections, the mechanisms of how exactly this is working and which particular elements of that community are important are still being worked out…And then for other conditions for which fecal transplants have been tried, success rates are lower than for C. diff infections and more variable, more inconsistent between studies…It just speaks to how hard it is to do this kind of work — that altering someone’s microbiome is as complicated as changing a rainforest or a coral reef.”

Ethical and regulatory questions raised by fecal transplants

“Fecal transplants, I think, raise some interesting ethical issues and regulatory issues because they’re so easy to do. You know, anyone can do them in their own home with a donor and a blender and some tubing…You hear stories about people doing fecal transplants for, say, kids with autism, and I think this is a potential problem. It’s something we need to think about really hard…There are many experiments where we see that stool transferred between rodents can transfer the symptoms of many disorders, anything from atherosclerosis to diabetes to colorectal cancer, so given that, you’re taking now stool from an adult and putting it into a child that’s still developing with not really a huge amount of data on the potential risks or long-term consequences of doing that. So, I sort of feel that there needs to be discussion about the regulatory side of this — of some of the ethics of doing this kind of work — even as we are marching into this future where this therapy is increasingly proving its worth and we’re learning more about it. I think that excitement ought to be tempered with a reasonable amount of caution too.”

Other applications for microbiome research outside of medical therapies

“There is this huge growing field of the microbiome of the built environment — what other microbial communities exist in the spaces around us, like in this chair or this rug, in the air and all these surfaces, and how are the choices that we are making contributing towards that, so in the design of the buildings and whether windows are open or not…This has particular relevance to a hospital setting, where you want to ensure that patients aren’t getting sicker, but maybe putting them in a super sterile environment, or an environment that you’re trying to sterilize but can’t completely, maybe that’s sort of making things worse. Maybe that’s creating more ecological vacancies in which nasty pathogens are more likely to colonize. I don’t think there are firm answers here because I think this area, much like a lot of the human microbiome, is still in its infancy. It’s still in kind of a descriptive stage where we’re learning who is where…I think it’s on the cusp of getting to a more predictive stage and then, finally, to a stage where we can actually manipulate it in a sort of deliberate and ingenious way.”

The importance of basic research

“You can’t just look at basic science and predict which bits of it are going to bear fruit in the future. You need to explore it for its own sake.”

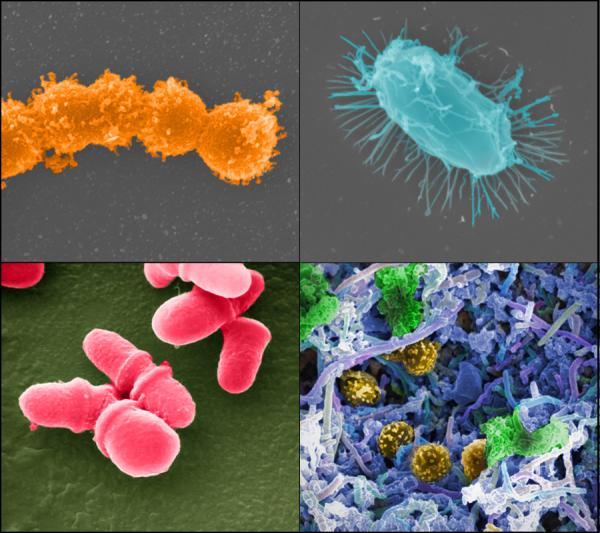

Microbes like those pictured above may one day form the basis of numerous medical treatments.

How scientists can communicate more effectively with the public

“I think a lot of people think about science as a set of discoveries or papers, but it’s so much more than that. It’s the lives of everyone in this room, it’s stories of successes and failures, it’s the motivations that got people into this in the first place, it’s tales of feeling out of place or curious about something. And it’s these human universals that I think make science so compelling…Good science writing and good science communication is not just about translating science. It’s not about just taking a study and explaining it in lay language. It’s also about explaining how that science came to be — the stories behind it and the stories of the people behind it.”

Dangers of over-hyping scientific results

“It’s also important to get across some of the uncertainty that is inherent in science. I think that is something that journalists could do a better job at. It is something that scientists could do a better job at when they talk to journalists…I don’t think you need to tell people that you’re going to change their lives or change the world in order to get them excited about science. I think those elements that I’ve talked about — those very human things of people doing stuff and changing as a result — are just so common to all the work we do, and I think are just a wonderfully powerful way of getting people interested in things that they would have otherwise no interest in at all and that don’t require hype or exaggeration to work.”

How writing this book has affected Yong’s worldview

“This is one of the things that really drew me to this field: the conceptual change that it creates in the way that we see ourselves and the other living things around us and our relationships with them. So to see an individual, a single body with a single brain and a single genome, as really an entire world in their own right, I think, is a beautiful and wonderful idea — the idea that my forearm is a very different ecosystem to my mouth and my gut, the idea that I am home to so much life that I am crucially dependent on, and that that extends to the entire animal kingdom…I love it because it tells me that all the things I was familiar with — all the biology I grew up learning as a kid and at school — is only a fraction of the true biology that exists. And without understanding this hidden world of all these underdogs that, as I’ve said, we’ve feared and reviled, we don’t really understand how we ourselves work.”

As scientists continue to learn more about how our microbes influence health and disease, microbiome-based therapies may soon find their way into applications for treating a wide array of conditions. Click the following links to learn more about IRP research into the microbiome:

- The Human Microbiome Project… And the Intramural Connection

- IRP Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Scientific Focus Area

- IRP Investigators Dedicated to Microbiome Research

Related Blog Posts

This page was last updated on Monday, January 29, 2024