State of the Arts

A Mosaic of Medicine, Music, and Art at the NIH

BY MICHAEL TABASKO, THE NIH CATALYST

CREDIT: PHOTO GENERATED WITH AI, DORACLUB

Learn more about how NIH scientists, staff, and clinicians integrate the arts into biomedical research, clinical trials, and the campus and clinical center environment.

When Bob Marley belted out that iconic opening line to Trenchtown Rock, “One good thing about music, when it hits you feel no pain,” he was likely relating to the power of music to uplift the human spirit. But he may have been onto something more than the metaphorical.

Although it’s no secret that engaging in music and the arts enhances the wellbeing of individuals and communities, science is only beginning to explain why.

The NIH has long been a welcoming canvas for art in all its forms, well before the term neuroarts was coined. Consider the college-like Bethesda campus with its bucolic green spaces and a critical mass of artist-scientists and creative types. Tune into a performance by NIH-based musical ensembles such as the NIH Philharmonia or Affordable Rock’n’ Roll Act. Pause and take in a tapestry of thoughtfully curated art exhibits that welcome inspiration and contemplation throughout the Clinical Center (CC), Building 10, and Porter Neuroscience Research Center, Building 35. For patients being treated at the CC or participating in clinical research, art therapy is often prescribed as a way to self-express and heal. Then there’s the research uncovering precisely how the different components of art infiltrate our senses.

Understanding a medley of mechanisms

Learn more about the NIH Sound Health Network, the Trans-NIH Music and Health Working Group, and recent publications on music and the mind at https://www.nih.gov/sound-health.

In 2017, NIH convened a first-of-its-kind workshop on music and health that brought together the likes of neuroscientists, researchers, music therapists, and other experts in the field to talk about the possibility of merging medicine and music together for therapeutic potential.

That meeting was an early step in the Sound Health partnership and cochaired by then-NIH director and musician-scientist Francis Collins and renowned soprano Renée Flemming, who cochairs the NeuroArts Blueprint Initiative. A resulting paper published in Neuron (PMID: 29566791) laid the groundwork to push the field forward. Soon after, the Trans-NIH Music and Health Working Group was formed and has since ushered along a newly focused wave of research into arts- and music-based interventions.

Nearly $40 million has since been invested into such research through Sound Health. The idea is that if an aligned research agenda could tease out the “active ingredients” in music and art, develop new technologies to reveal mechanisms by which those ingredients affect the body, and then design robust, reproducible studies to inform what an effective dose looks like—and for whom—then we might someday be able to prescribe artful engagement as a health behavior.

CREDIT: CHIA-CHI CHARLIE CHANG

Francis Collins continues to pick up his guitar and advocate for more research into music-based interventions. “A lot of people are seeing this [research] as a window both into how the brain works, [and] how we can come up with something that would help people who are suffering from chronic pain or PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] without having to take a pill. Listen to the right kind of music; you’ll be much better,” said Collins during a guest appearance on the Late Show with Stephen Colbert on September 17. Shown here is opera singer Renée Fleming and Collins singing together at NIH during the 2019 J. Edward Rall Cultural Lecture. Learn more: https://youtu.be/1d-PlEAQMBY

Speaking at the "Music as Medicine: The Science and Clinical Practice" workshop in December 2023, Collins delivered a keynote address on what has been accomplished since 2017, and the results are encouraging.

He highlighted NIH-supported studies that showed infants exposed to musical training could track changes in language tone better than infants not exposed to music (PMID: 36016666); that learning to play a musical instrument was associated with improved cognitive function and language development in adolescents (PMID: 36757558); and that learning to drum reduced hyperactivity and inattention in autistic children and resulted in measurable brain changes revealed by brain imaging (PMID: 35639696).

“I think a lot of this is the wave of the future of where we’re going as to taking advantage of these really powerful technologies to not just make observations but actually understand mechanisms at the level of circuits in the brain,” said Collins in his keynote address. “I would love to see us bring the fields of music therapy and neuroscience even closer together. That has been part of the dream all along; to make it possible for the remarkable things that music therapy can achieve to be better understood.”

Quickening the tempo

“There’s a lot of momentum that’s building up,” said Emmeline Edwards, director of NCCIH’s Division of Extramural Research, and coauthor with Collins on the NIH Music-Based Intervention (MBI) Toolkit, which laid the building blocks of how to conduct high-quality studies on music-based interventions for brain disorders of aging (PMID: 36639235). “The MBI toolkit falls in place with the rigor and reproducibility policy at NIH,” said Edwards, adding that feasibility trials are now underway to test how well the toolkit’s guidelines are able to improve research quality.

The components of the MBI toolkit were designed to be translated to other art forms, according to Edwards. “We started with music and brain disorders of aging because we had the most data in that area,” she said. “In phase two of Sound Health, currently happening now, we want to start investigating other art forms like dance and performing arts. We partnered with the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts to do a workshop on the neural basis of creative movements, and we have a set of investigators working on that. This is the work that needs to be done before we design an intervention that makes sense.”

The therapeutic potential of music and other art forms on pain represents another intriguing direction. “[Music and art] are noninvasive, low cost, and most people like interacting with the arts,” said Edwards. “Maybe we could suggest that some of our investigators in the funded pain research networks program give talks in the IRP. That’s something that we could stimulate and see where it goes.”

Looking ahead, a primary goal in the arts-intervention field is to move toward the concept of social prescribing, already ongoing in Europe (PMID 10735850) and in some local health departments in the United States (PMID: 36743160). “This is the blue-sky idea, to prescribe these art-based interventions in conjunction with conventional medicine,” said Edwards.

Learn more about music and the mind at the February 25 Demystifying Medicine lecture. Francis Collins will introduce speakers Joshua Roman, a cellist with long COVID, and Charles Limb, a professor of otolaryngology from the University of California at San Francisco. Limb was a postdoctoral fellow at NIDCD and now studies the neural basis of musical creativity and perception.

New technologies have revealed how music might change the brain. Yuanyuan “Kevin” Liu, a Stadtman investigator in NIDCR’s Somatosensation and Pain Unit, found that playing sound—any type of sound, from Bach to white noise—at a level five decibels over ambient levels suppressed pain in mice with inflammation pain (PMID: 35857536). “Interestingly, [analgesia] can have a long-lasting effect,” said Liu. “If you play music or sound for three days, the effect can last for an additional two days. That suggests it is not just that attention is shifted away from pain but that there could be long-lasting circuit-level changes.”

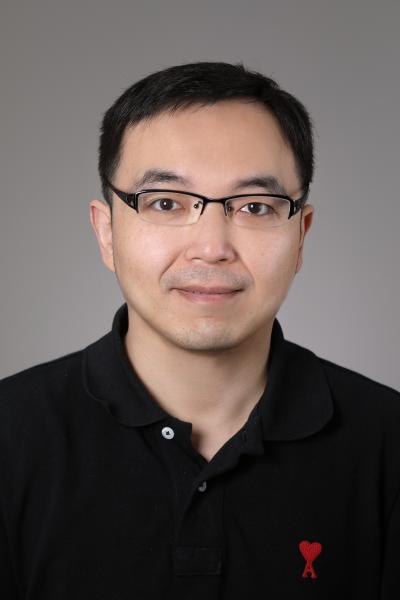

CREDIT: NIDCR

Yuanyuan Kevin Liu

To find those circuits, Liu and colleagues used high-resolution electrical recording techniques to monitor how 5-decibel sound reduced activity in the auditory cortex of the brain. Viral tracers then tracked those cortical signals downstream to two regions in the thalamus known to process somatosensation and pain, providing anatomical evidence of the connection. Then, optogenetic and chemogenetic techniques were used to turn the corticothalamic circuit on or off, proving that the circuit is both necessary and required in sound-induced analgesia.

His paper has sparked two new directions, according to Liu. First, he is looking at the mechanisms behind how loud noise could exacerbate pain. Second, his team is exploring how music and sound could affect autonomic functions such as heart and breathing rate, which could give insights into mind-body control.

Liu advocates for more communication between pain labs like his and clinicians using music as treatment. “We really should encourage talk between basic scientists and clinicians who are working on this mind-body connection. What have they learned; do they see an autonomic change?”

From canvas to cortex

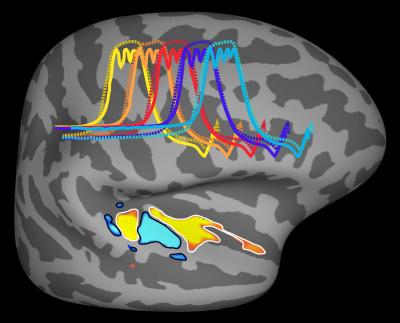

CREDIT: BEVIL CONWAY LAB, NEI

Graphic illustration from Conway’s 2019 research showing areas of the human auditory cortex which are uniquely sensitive to sound frequencies used in music and speech.

Mapping how the human brain integrates audio and visual inputs could give insight into how people (and other primates) experience art in different ways. For example, a Sound Health-funded project revealed that the human auditory cortex is uniquely tuned to pick up on harmonic tones compared with that of monkeys, suggesting a brain-shaping evolutionary role for speech and music (PMID: 31182868). That work was led by Bevil Conway, who is now a senior investigator at NEI’s Sensation, Cognition, and Action Section.

Conway’s team also studies how visual perception and color are processed in the brain, using technology such as magnetoencephalography, which noninvasively measures neural electrical impulses. His lab revealed that people show similar neural patterns of activation in response to color, suggesting that how we humans perceive color is one thing we have in common (PMID: 33202253). Interestingly, warm hues such as red, orange, and yellow generated more specific patterns of brain activity than cool colors like blue and green, another finding likely due to evolutionary pressures, according to Conway.

Ideas of art are ultimately concepts, explains Conway, and his lab is aiming to understand the origin of concepts, using color as a model system. “The rainbow is continuous, but humans tend to carve it up into categories such as ‘red,’ ‘orange,’ and so on,” he said. “These categories are examples of concepts, hallmarks of intelligent systems such as the human mind. We would like to know how concepts form, the extent to which they are innate, how we acquire new concepts, and how we update our concepts with new information. We think the same principles that apply to concept formation about colors will apply to concept formation about art, so understanding art better might therefore be instructive.”

Conway is among several artist-scientists at the NIH. He creates art using glass and silk, etching, watercolor, and oils. You can see four of his pieces on display at the Porter Neuroscience Research Center. Learn more about Conway’s work on color and the mind on the Speaking of Science Podcast.

At the CC’s Rehabilitation Medicine Department, art therapist Sarah Thuermer recalls one of her international patients undergoing bone marrow transplant for severe aplastic anemia turned acute myeloid leukemia. The patient was struggling with depression, anxiety, and coming to terms with a new sense of self if her disease was cured.

CREDIT: SARAH THUERMER

Sarah Thuermer

“Patients use art to express, explore, and process emotions through their entire journey and to increase self-esteem and find identity beyond their illness,” said Thuermer, who taught her patient how to create masks using symbols and colors as a form of self-expression. “On her very last day, she made a beautiful mask about hope and growth; and on the back, she wrote meanings to each symbol that she created and what each color meant.”

Art therapy can reduce psychological distress (PMID: 34898951) and arts-based programming has been shown to enhance the mood, health, resilience, and wellbeing of people living with chronic health conditions (PMID: 38384874). From acrylics to photography, art therapy centers around each patient’s emotional needs and mental health goals, according to Thuermer. “A lot of patients have emotions that they don’t quite understand yet or are unaware of, and those might come out in art. I help guide them to process those emotions toward healing.”

Technologies such as virtual reality and photography apps are making art therapy more accessible and age-appropriate for teenagers, according to Thuermer. Some apps allow those patients to virtually paint graffiti on walls, choosing their color and designs with the added benefit of getting them up and active during their hospital stay.

“Nonverbal expression is important,” added Donna Gregory, chief of the Recreational Therapy Program. “We see pretty much every patient dealing with a rare disease, stressful diagnosis, or stress of being involved in clinical research. Sometimes art therapy is safer and easier than trying to use words.”

SAVE THE DATE: Don’t miss the NIH Philharmonia’s “We Three Ships” performance on Dec. 7 at Elizabeth Catholic Church in Rockville, Maryland.

Enhancing the Aesthetic Experience

CREDIT: LILLIAN FITZGERALD

Artwork in five changing exhibits is available for sale with a percentage of the proceeds going to the Patient Emergency Fund. Administered by the CC Social Work Department, the fund provides emergency food, housing, and clothing to patient families in need.

The NIH CC, at the heart of the NIH Bethesda campus, is very much the hub of the NIH art scene. The Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center, the so-called north side of Building 10, is filled with museum-quality original pieces, many of them donated by local artists—some of whom were patients themselves—adorning light-filled airy spaces on several different levels.

Lillian Fitzgerald, curator of the CC’s Fine Art Program, is particularly fond of the mixed-media painting “Ca D’Oro” by artist Gail Watkins on the west side of the 7th floor. “It looks like an ancient, ruined wall with golden triangles. People have gravitated to it because it is so meditative,” said Fitzgerald.

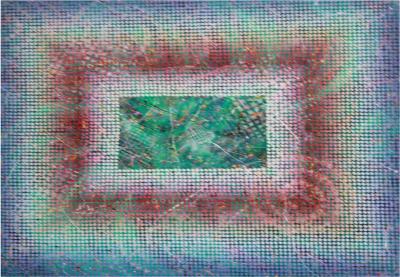

CREDIT: LILLIAN FITZGERALD

Shown is “River Cells” by Paula Crawford, who is an artist and professor of fine arts at George Mason University (Fairfax, Virginia). She was also a CC patient who participated in an NIH NIDDK clinical research trial to treat chronic hepatitis C. After her treatment, Crawford spent several months painting “River Cells” with the intention to donate it. The artist said she strove to create a painting that evoked water flowing over river stones and also the view of hepatitis C virus cells through a microscope.

The Fine Art Program was established in 1984 after a request to the CC director from oncology staff to soothe pediatric patients. Enhancing the aesthetic experience of patients and staff continues to be the focus. “We want to put patients at ease, and part of what we do with the artwork is to transform their hospital experience into something less frightening, make sure they feel supported, and alleviate their fears,” said Fitzgerald. She noted that the collection comprises more than 2,000 original paintings, medical illustrations, photographs, sculptures, ceramics, glass, pottery, and textiles, and that each piece was carefully chosen as a source of respite, hope, and inspiration.

CREDIT: LILLIAN FITZGERALD

Shown is “Big Red Dog” by Raya Bodnarchuk (1947–2021), a Rockville, Maryland-based artist, who produced abstract wooden animal figures from shapes that inspired her, often working with a chainsaw. Her work is also featured in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (Washington, D.C.). For many years, “Big Red Dog” was prominently displayed in the CC Pediatric Wing. It is now located on the 3rd floor south lobby. Raya was also a patient at the Clinical Center.

Fine art as a muse for cutting-edge research is on display throughout the Porter Neuroscience Research Center, which began as a blank slate. “When the center was completed, there was no art budget [and] a lot of white space and blank walls,” said Jeffrey Diamond, NINDS’ scientific director and de facto curator of the Porter Arts Program. “When the opportunity presented, I would talk to artists about our building and tell them I would be happy to display their art.”

CREDIT: LILLIAN FITZGERALD

Carol Brown Goldberg donated this painting titled “If You Believe, You Get First Choice,” after her young son was treated for serious disease at the Clinical Center.

The approach worked. Visitors to the soaring atrium in Building 35 are treated to a trio of neuroscience-inspired tapestries by Lia Cook, generated by a computerized loom. Then there is the digital artwork of Elizabeth Jameson, inspired by her own magnetic-resonance images that were done to check the progression of her multiple sclerosis. Rebecca Kamen, an artist-in-residence when the center opened, has since donated several of her original sculptures. Perhaps most famous, the first floor hosts a rotating series of exquisite drawings by Nobel Laureate Santiago Ramón y Cajal, known as the father of modern neuroscience, circa 1900, on loan from the Cajal Institute in Madrid, Spain.

“The exhibits get people thinking. Science is a creative endeavor, and it’s neat to have different ways to stimulate that creativity,” said Diamond.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, November 5, 2024