From the Deputy Director for Intramural Research

Technologies: They Work for Us (Not the Other Way Around)

BY NINA F. SCHOR, DDIR

When I was an undergraduate student, I spent my entire senior year doing chemistry research in the laboratory of Julian Sturtevant. We discerned the 3D structure of proteins using circular dichroism spectroscopy and the thermodynamics of protein unfolding after disulfide bond reduction using a calorimeter made in Moscow by Peter Privalov that had the serial number 00003. We did not have personal computers or cell phones or even pocket-sized calculators. In fact, in a wonderful cartography course, I used punch cards for the first time to generate maps!

When I was a graduate student in the laboratory of Anthony Cerami, I ran hydrolyzed protein samples on an amino acid analyzer that spanned a whole wall in a large room and took overnight to run my samples. I analyzed the dot matrix printout it generated using a handheld planimeter. I packed my own gas-liquid chromatography columns and poured my own acrylamide gels by hand. As a medical student, I saw one of the very first computed tomography (CT) scans of the head. The pixels were so large and so few that it looked like a child’s jigsaw puzzle!

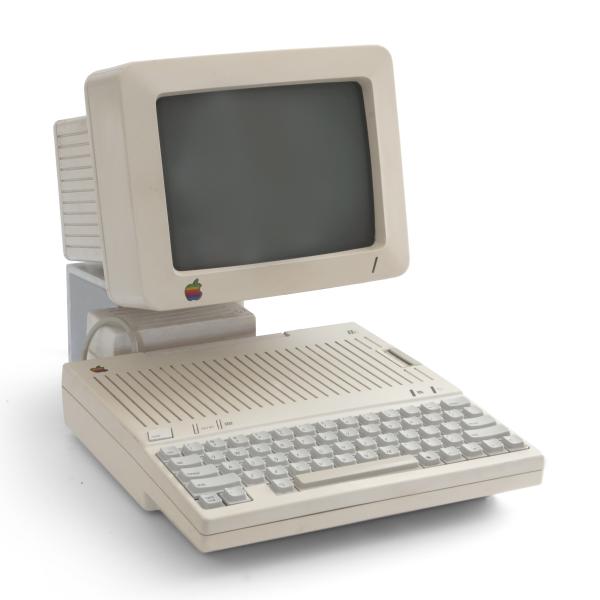

CREDIT: APPLE

The Apple II-C was released April 24, 1984, and was considered a portable computer at the time.

As a resident physician, I bunched up all my elective time at the end of my final year so I could spend six straight months in the lab of Manfred Karnovsky. I bought my first pocket-sized calculator and used an Apple II-C computer and a program called Cricket Graph to make figures for publication. By the time I was a new assistant professor, “technology” meant having a PC and a dot matrix printer on your desk and a magnetic resonance imaging scanner in your Department of Imaging Sciences. By the time I was a professor, transcriptomic chips had 40,000 cDNAs on them and most adults had a cell phone.

Technology moves very fast—sometimes faster than ethics and analytics can keep pace. Now, I feel as if I am the only person left on earth who does t-tests and Mann-Whitney U-tests by hand. Doing so makes me think deeply about whether I am doing the right test for the question I am asking; whether the results make sense; and what the results mean beyond statistics into the biology and chemistry of the system. I have read more than I think is good for me about artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs). I am deeply fearful of what they will convince us we know that we do not, and what they will make us think we understand that we have wrong. We are sharing datasets generated without a driving hypothesis and publishing post hoc analyses before generated hypotheses are tested.

This issue of the NIH Catalyst is about emerging technologies. They are alluring and exciting and filled with potential. But they are tools, and their value is not intrinsic. What they enable us to understand, and what we do with that understanding, are what matters. It feels as if the cutting-edge technologies described in this issue can expand our research efforts to boundless frontiers, but we must think about and use these innovations wisely, cautiously, and thoughtfully, while leveraging our creativity and our ethics as we work to extend the health span of all people everywhere.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, December 3, 2024