Blood, Sweat, and Tears

Conference Explores New Frontiers in Liquid Biopsies

BY JENNIFER HARKER, THE NIH CATALYST

When NIH scientists use the phrase “blood, sweat, and tears,” they mean it. Literally. In fact, we can join them on May 13–14 to learn more about all the ways in which scientists at NIH and around the world are exploring blood, sweat, tears, and other bodily fluids as liquid biopsies to travel to new frontiers for human health and disease.

“We really accomplished our goal of bringing together a diversity of ideas that span from maternal fetal genetics to almost every liquid biopsy modality you can imagine,” said Adam Sowalsky, senior investigator in NCI-CCR’s Prostate Cancer Genetics Section and one of the conference organizers. “So, there are talks about blood serum and plasma, amniotic fluid, cerebral spinal fluid, saliva, tears, sweat—all the minimally invasive liquids that people have figured out how to co-opt for monitoring disease, diet, disease detection, and of course, precision medicine.”

Each of these liquid biopsy applications will be featured during panel discussions and research poster presentations at the two-day conference sponsored by NCI-CCR and NHLBI, to be held at the Natcher Conference Center (Building 45) on the Bethesda campus. Among the conference highlights is an international roster of speakers, including the opening keynote lecture on Monday, May 13, which will feature Dennis Lo, professor of medicine at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who was a 2022 recipient of the Lasker~DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award. Lo will provide an introductory talk on efforts to detect cancer earlier by measuring DNA that freely circulates in blood plasma.

Check out the full conference agenda here https://ncifrederick.cancer.gov/events/conferences/2024LiquidBiopsyConference/agenda.

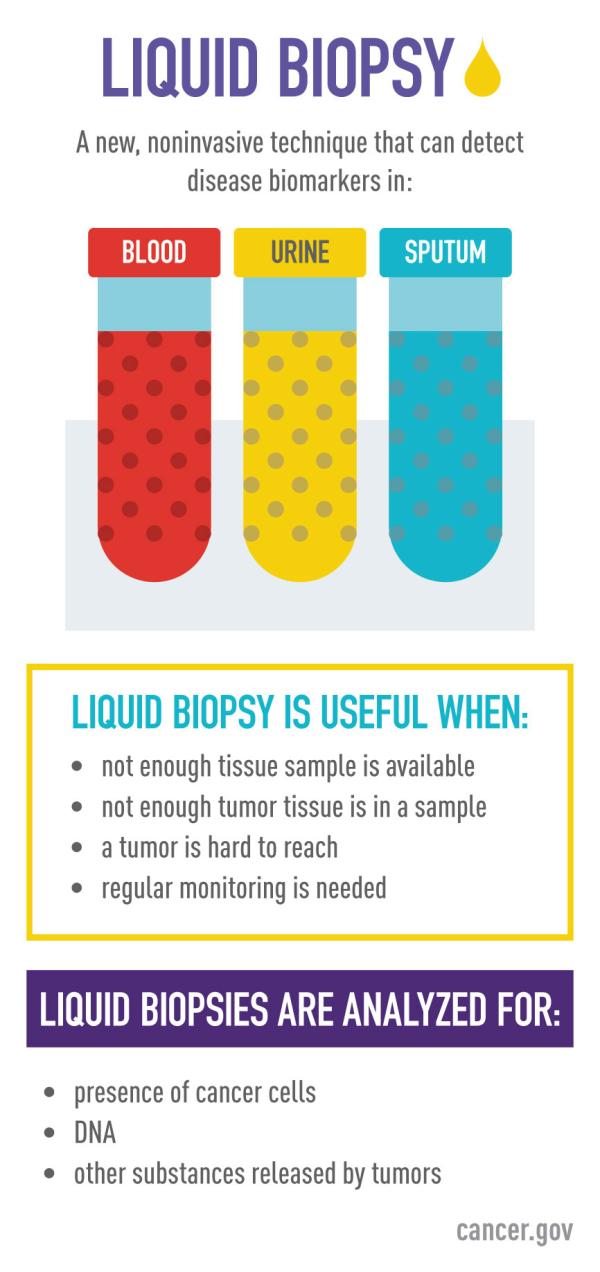

What are liquid biopsies?

Liquid biopsies offer an alternative to tissue sampling for diagnosing, treating, and monitoring disease. Liquid biopsies can be analyzed for various biomarkers including cell-free DNA (cfDNA), extracellular vesicles such as exosomes, and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), to name a few (PMID: 37716353).

Scientists are discovering new ways in which tumors or even transplanted organs shed various biomarkers into the bloodstream, or into other body fluids, that offer enough information to enable reduction of traditional tissue sampling. This process reduces the need for risky procedures in difficult-to-reach areas and lowers the risk of infections or even stress that patients experience from invasive tissue sampling procedures.

Monitoring metastasis

Some cancers and conditions can be partially diagnosed using a liquid biopsy, but the true value of liquid biopsies is in its monitoring capabilities. For example, monitoring CTCs reveals that there really is strength in numbers.

Breast cancer mortality is almost always due to metastasis, so understanding how cancer cells survive the march from primary tumor to metastasis has grown to become a very important research aspect for Esta Sterneck, head of the Molecular Mechanisms in Development Section at NCI-CCR and conference co-organizer.

“We monitor circulating tumor cells that travel as groups termed ‘clusters’ because they are deemed more likely to seed metastasis compared to single tumor cells,” she explained, adding that she is studying how cell-to-cell adhesions may enhance tumor cell survival and might, therefore, be targeted for therapeutic intervention. Toward this aim, Sterneck’s lab also uses an unconventional 3D cell culture paradigm for mechanistic molecular studies (PMID 36757813) and uses mouse cancer models to validate findings by use of liquid biopsies.

Esta Sterneck, NCI-CCR

One might liken the usefulness of these findings to planning a war strategy: Attack while the enemy is on the move and most vulnerable. “It has been shown that circulating tumor cells surge during surgery or even biopsy, so these are times in patient care during which one might want to particularly target circulating tumor cells to minimize the spread that could accompany these interventions,” she said.

“The hope is that one day liquid biopsies can become a complementary diagnostic tool to identify cancer cells in the body, but right now, it is really for monitoring current states of cancer and how it progresses in the body: What is happening now, how the secondary sites are occurring, and how it is travelling within the body.”

Sterneck said she hopes the conference will help to connect basic and clinical researchers and thereby contribute to new research directions and collaborations among attendees.

Real-time therapeutic response

Liquid biopsies as a diagnostic tool don’t always make sense, as Sowalsky might tell you. His first attempt at investigating circulating tumor DNA paired with a hypothesis that put a liquid biopsy approach up against the existing prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test.

“Ultimately, we published my first negative data paper saying that it is just not there, we could not detect it (PMID: 31528835). So far, that has been the experience of almost everyone else we have talked to, and they are glad that we published the negative data paper because it sets the stage for what we cannot do and now we can focus our efforts on something else.”

Those efforts have led to NIH clinical studies in which patients with progressed disease receive combination immunotherapy, inhibitor treatments, or other trial drugs (PMID: 30514390, PMID: 33023952; see also, PMID: 36179684, PMID: 33422353). Sowalsky’s team tracks patient progress during these treatments using serial blood samples.

Adam Sowalsky, NCI-CCR

“We thought we could try a number of different types of analyses to understand the basis for response,” Sowalsky said. “So, we asked, is there something about the circulating tumor DNA or the cfDNA from those patients that would tell us that they would respond or why they did not respond?” The research team examined the liquid biopsies for tumor evolution and monitored whether patients experienced clinical progression.

“We figured out a number of different ways we can approach these questions. One way is looking at mutations and somatic mutations, somatic copy number of alterations, actual structural things that happened to the DNA itself. For example, there could be a mutation and therefore a change in the clonal abundance of the tumor. So, something that was insignificant early in the disease became more important later, and that is what may have driven resistance to the therapy. Or there could have been intrinsic resistance where the patient had a certain combination of mutations that rendered that patient resistant, initially. We did not know any of these things going into the clinical trial, but having this information now will be useful for the next stage of clinical interrogation.”

Less invasive transplant rejection monitoring

Liquid biopsies reduce the number of invasive needle or tissue biopsies. For lung transplant patients, liquid biopsies are making rejection monitoring much less painful and expensive.

Sean Agbor-Enoh, a Lasker clinical research scholar at NHLBI who specializes in pulmonary transplant medicine, grew deeply concerned about patients during the COVID-19 pandemic, not only about the possibility of their contracting the deadly virus but also because of the lack of access to safe health care procedures to monitor for the first signs of organ rejection after transplant.

Traditionally, lung transplant patients undergo seven or more invasive lung biopsy procedures over the first two years post-transplant. These expensive biopsy procedures required anesthesia and a hospital stay, which became risky during the pandemic.

So, Agbor-Enoh partnered with industry professionals and other federal agencies to develop a cfDNA liquid biopsy that can detect rejection two to four months earlier than the traditional tissue biopsy. The cfDNA liquid biopsy approach distinguishes between the host and the organ donor DNA, and as long as the donor DNA stays at a low concentration, the patient’s prognosis remains positive (PMID: 30692045).

Sean Agbor-Enoh, NHLBI

Read more about Agbor-Enoh’s work and view a recent video interview in this Research In Action segment.

These patients now can be monitored via a monthly blood draw and the alarm signals (increase in donor DNA) can be identified sooner, medications can be adjusted quicker, and secondary infection rates from invasive procedures are minimized. This procedure has resulted in an 85% reduction of the traditional tissue biopsy for lung transplant patients (PMID: 35063338), and upward of 60–75% of transplant centers now use the liquid biopsy test. According to Agbor-Enoh, it is quickly becoming the standard of care for other types of transplanted organs as well (PMID: 38380175, PMID: 38026221).

“This is quite a paradigm shift,” he said. “With just one milliliter of blood from a blood draw not only can one do a diagnosis, but also a prognosis, with quite some degree of accuracy. Importantly, these principles could be broadly applicable in non-transplant diseases [PMID: 38165046, PMID: 36004627, PMID: 38117233]. So, as you can imagine, this could completely change the way we practice medicine.”

From SIG to an international exchange of ideas

As with most scientific discoveries, there is a long and storied history, but long story short is that Sowalsky, Sterneck, and Agbor-Enoh joined forces through the Liquid Biopsies Scientific Interest Group (SIG) to spearhead the New Frontiers in Liquid Biopsies conference.

“I wanted to develop a disease-agnostic international intellectual network of individuals who were interested in sharing ideas, technologies, method development, best practices—and not just sharing research achievements but the nitty gritty things like what methods you’ve used and how did you get it to work, what challenges you encountered along the way, what didn’t work, and what should we or should we not try,” said Sowalsky about his thoughts behind both the NIH SIG and the May 13–14 conference.

“We have all been working in silos in our own smaller corners,” added Agbor-Enoh. “I do lung transplant; Adam does prostate cancer; Esta works with preclinical mouse models; we all do exciting things with different types of liquid biopsies; but can you imagine if you bring all of us into the same sandbox such that we can talk about what we do and learn from each other? It could be an even bigger course in the field of liquid biopsy. That’s the excitement in the conference. We expect that participants coming to the conference will learn a great deal and then can take that information back to their respective corners and increase what they know while fostering collaborations.”

Other conference co-organizers include Aadel Chaudhuri at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minnesota), Alexandra Miller at New York University Langone Health (New York), Aaron Newman at Stanford University (Palo Alto, California), Bruna Pellini at the Moffitt Cancer Center (Tampa, Florida), Antoinette Perry at University College Dublin (Belfield, Dublin, Ireland), and Ignatia Barbara Van den Veyver at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston, Texas).

“The conference will be a great exchange of knowledge and ideas, and our intent is for it to serve as a platform for new collaborations,” said Sowalsky.

NIH IDENTIFY Study

Over 100 cancers have been detected in pregnant women by analyzing liquid biopsies through the NIH IDENTIFY Study, led by Diana Bianchi, director of the NICHD and head of the Prenatal Genomics and Therapy Section for the Medical Genetics Branch at NHGRI; and Christina Annunziata, who recently left NCI-CCR for a new role at the American Cancer Society.

For more information on the ongoing IDENTIFY study, visit https://www.genome.gov/IDENTIFY, and read past coverage here.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, December 3, 2024