Research Briefs

NHLBI, NHGRI: TO SLEEP OR NOT: RESEARCHERS EXPLORE COMPLEX GENETIC NETWORK BEHIND SLEEP DURATION

CREDIT: THINKSTOCK.COM

NIH scientists identified differences in a group of genes that might help explain why some people need a lot more sleep—and others less—than most. The researchers used fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) populations bred to model natural variations in human sleep patterns. The study provides new clues to how genes for sleep duration are linked to a wide variety of biological processes. A better understanding of these processes could lead to new ways to treat sleep disorders such as insomnia and narcolepsy.

Scientists have known for some time that, in addition to our biological clocks, genes play a key role in sleep and that sleep patterns can vary widely. But the exact genes controlling the duration of sleep and the biological processes that are linked to these genes have remained unclear.

In the study, the scientists artificially bred 13 generations of wild fruit flies to produce flies that were either long sleepers (sleeping 18 hours each day) or short sleepers (sleeping three hours each day). The scientists then compared genetic data between the long and short sleepers and identified 126 differences among 80 genes that appear to be associated with sleep duration. They found that these genetic differences were tied to several important developmental and cell-signaling pathways. Some of the genes identified have known functions in brain development as well as roles in learning and memory.

The researchers also found that the lifespan of the naturally long and short sleepers did not differ significantly from the flies with normal sleeping patterns. This finding suggests that there are few physiological consequences of being an extremely long or short sleeper. (NIH authors: S.T. Harbison, Y.L. Serrano Negron, N.F. Hansen, and A.S. Lobell, PLoS Genet 13:e1007098, 2017)

NIDCD, NIMHD, NCATS: CLUES ABOUT WHY A COMMON CANCER DRUG CAUSES HEARING LOSS

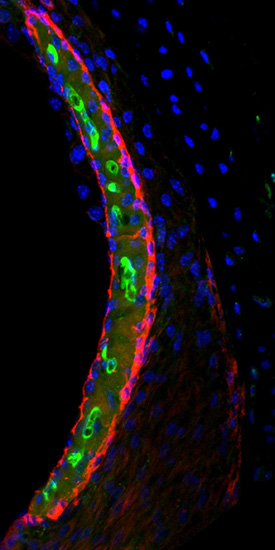

CREDIT: NIH

Cisplatin (green) in the stria vascularis of a mouse inner ear.

The chemotherapy drug cisplatin can cause permanent hearing loss in 40 to 80 percent of adult patients and at least half of children who receive the drug. NIH scientists have found a new way to explain this hearing loss. Using a highly sensitive technique to measure and map cisplatin in mouse and human inner-ear tissues, the researchers found that forms of cisplatin build up in the inner ear. In particular, the highest buildup of the drug is in a part of the inner ear called the stria vascularis, which helps maintain the positive electrical charge in inner-ear fluid that certain cells need to detect sound. The findings suggest that if cisplatin can be prevented from entering the stria vascularis in the inner ear during treatment, cisplatin-induced hearing loss may be prevented. (NIH authors: A.M. Breglio, A.E. Rusheen, E.D. Shide, K.A. Fernandez, K.K. Spielbauer, M.D. Hall, L. Amable, and L.L. Cunningham, Nat Commun 8:article number 1654, 2017; DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-01837-1)

CC: CHEMICAL FROM CACTUS-LIKE PLANT SHOWS PROMISE IN CONTROLLING SURGICAL PAIN

A promising approach to postoperative incision-site pain control uses a naturally occurring plant molecule called resiniferatoxin (RTX). RTX is found in Euphorbia resinifera, a cactus-like plant native to Morocco, which is 500 times as potent as the chemical that produces heat in hot peppers and may help limit the use of opioid medication while in the hospital and during home recovery.

NIH researchers found that RTX could be used to block postoperative incisional pain in an animal model. In the study, researchers pretreated the skin incision site with RTX to render the nerve endings in the skin and subcutaneous tissue along the incision path selectively insensitive to pain. Unlike local anesthetics, which block all nerve activity including motor axons, RTX allows many sensations, such as touch and vibration, as well as muscle function, to be preserved. Long after the surgery and toward the end of healing of an incision wound, the nerve endings grow back. Thus, pain from the skin incision is reduced during the recovery period.

RTX has been found to be a highly effective blocker of pain in multiple other preclinical animal models and is in a phase 1 clinical trial at the NIH Clinical Center for patients with severe pain associated with advanced cancer. (NIH authors: S.J. Raithel, M.R. Sapio, D.M. LaPaglia, M.J. Iadarola, and A.J. Mannes, Anesthesiology 128:620–635, 2017; DOI:10.1097/ALN.0000000000002006)

NICHD: NIH RESEARCHERS REPORT FIRST 3-D STRUCTURE OF DHHC ENZYMES

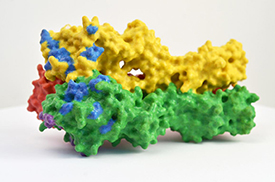

CREDIT: JEREMY SWAN, NICHD

Molecular view of DHHC palmitoyltransferases. Human DHHC20 (yellow) is embedded in the Golgi membrane (green), a compartment located inside cells. DHHC20 attaches a fatty-acid chain (white) to a target protein (blue, foreground), which anchors the protein to the Golgi membrane.

The first three-dimensional structure of DHHC proteins—proteins that contain a 50-amino-acid chain called the DCCT domain, act as enzymes, and are involved in many cellular processes, including cancer—explains how they function and may offer a blueprint for designing therapeutic drugs. NICHD researchers led a study in which they proposed blocking DHHC-domain activity to boost the effectiveness of first-line treatments against common forms of lung and breast cancer. However, there are currently no licensed drugs that target specific DHHC enzymes. (NIH authors: M.S. Rana, P. Kumar, C.-J. Lee, R. Verardi, and A. Banerjee, Science 359:eaao6326, 2018; DOI:10.1126/science.aao6326)

Go to https://irp.nih.gov/catalyst/v26i2/back-page-catalytic-research for full story.

NICHD: IODINE DEFICIENCY MAY REDUCE PREGNANCY CHANCES

Women with moderate to severe iodine deficiency may take longer to achieve a pregnancy than women with normal iodine concentrations, according to a study by researchers at NIH and the New York State Department of Health in Albany, New York. The study is the first to investigate the potential effects of mild to moderate iodine deficiency—common among women in the United States and the United Kingdom—on the ability to become pregnant. Iodine—found in seafood, iodized salt, dairy products, and some fruits and vegetables—is used by the body to regulate metabolism, as well as bone growth and brain development in children. Severe iodine deficiency has long been known to cause intellectual and developmental delays in infants.

The researchers analyzed data collected from 501 U.S. couples who were planning pregnancy from 2005 to 2009. The couples were part of the Longitudinal Investigation of Fertility and the Environment study, which sought to examine the relationship among fertility, lifestyle, and environmental exposures. The women provided a urine sample from which their iodine concentrations were measured. Each woman was also given a digital, at-home pregnancy test. Of the 467 women analyzed, iodine status was sufficient in 260 (55.7 percent), mildly deficient in 102 (21.8 percent), moderately deficient in 97 (20.8 percent), and severely deficient in eight (1.7 percent).

To estimate a couple’s chances of pregnancy during each menstrual cycle, the researchers used a statistical measure called the fecundability odds ratio (FOR). A FOR less than one suggests a longer time to pregnancy, whereas a FOR greater than one suggests a shorter time to pregnancy. The researchers found that women who had moderate-to-severe iodine deficiency had a 46-percent-lower chance of becoming pregnant during each menstrual cycle than women who had sufficient iodine concentrations. The authors concluded that if their findings are confirmed, public-health officials in countries in which iodine deficiency is common may want to consider programs to increase iodine intake in women of childbearing age. Women who are concerned they may not be getting enough iodine may wish to consult their physicians before making dietary changes or taking supplements. (NIH authors: J.L. Mills, G.M. Buck Louis, J. Weck, A. Giannakou, and R. Sundaram, Hum Reprod DOI:10.1093/humrep/dex379)

NIAID, NHGRI, NIAMS, NCI, NIDDK: MICROBES ON THE SKIN OF MICE PROMOTE TISSUE HEALING, IMMUNITY

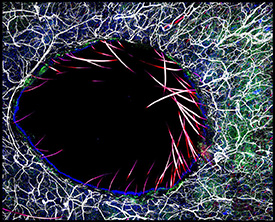

CREDIT: NIAID

Immunofluorescent image of immune cells surrounding a skin wound, enriched in the beneficial bacteria S. epidermidis.

Beneficial bacteria on the skin of lab mice work with the animals’ immune systems to defend against disease-causing microbes and accelerate wound healing. Untangling similar mechanisms in humans may improve approaches to managing skin wounds and treating other damaged tissues.

NIH scientists observed the reaction of mouse immune cells to Staphylococcus epidermidis, a bacterium regularly found on human skin that does not normally cause disease. To their surprise, immune cells recognized S. epidermidis using evolutionarily ancient molecules called nonclassical major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which led to the production of unusual T cells with genes associated with tissue healing and antimicrobial defense. In contrast, immune cells recognize disease-causing bacteria with classical MHC molecules, which lead to the production of T cells that stoke inflammation. Researchers then took skin biopsies from two groups of mice—one group that had been colonized by S. epidermidis and another that had not. Over five days, the group that had been exposed to the beneficial bacteria experienced more tissue repair at the wound site and less evidence of inflammation. The research team plans to next probe whether nonclassical MHC molecules recognize friendly microbes on the skin of other mammals, including humans, and similarly benefit tissue repair. Eventually, mimicking the processes initiated by the microbiome may allow clinicians to accelerate wound healing and prevent dangerous infections, the researchers note. (NIH authors: J.L. Linehan, O.J. Harrison, S.-J. Han, A.L. Byrd, I. Vujkovic-Cvijin, A.V. Villarino, S.K. Sen, J. Shaik, M. Smelkinson, S. Tamoutounour, N. Collins, N. Bouladoux, A. Dzutsev, S.P. Rosshart, J.H. Arbuckle, T.M. Kristie, B. Rehermann,. Trinchieri, J.M. Brenchley, J.J. O’Shea, and Y. Belkaid, Cell DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2017.12.033)

NIA: COMPOUND PREVENTS NEUROLOGICAL DAMAGE, SHOWS COGNITIVE BENEFITS IN MOUSE MODEL OF ALZHEIMER DISEASE

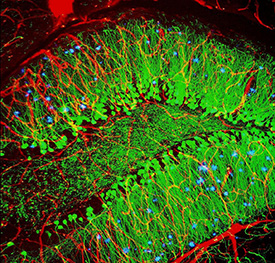

CREDIT: ALVIN GOGINENI, GENENTECH

The brains of mouse models treated with the supplement nicotinamide riboside showed reduced tau and less DNA damage than brains of nontreated mice. Shown: blood vessels (red), nerve cells (green), and abnormal protein clumps known as plaques (blue). These plaques multiply in the brains of people with Alzheimer disease and are associated with the memory impairment characteristic of the disease.

The supplement nicotinamide riboside (NR)—a form of vitamin B3—prevented neurological damage and improved cognitive and physical function in a new mouse model of Alzheimer disease. The results of the study, conducted by researchers at NIA and an international team of scientists, suggest a potential new target for treating Alzheimer disease. NR acts on the brain by normalizing concentrations of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a metabolite vital to cellular energy, stem-cell self-renewal, resistance to neuronal stress, and DNA repair. In Alzheimer disease, the brain’s usual DNA-repair activity is impaired, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction, lower neuron production, and increased neuronal dysfunction and inflammation.

Over a three-month period, researchers found that mice who received NR showed reduced tau in their brains but no change in amyloid-beta. The NR-treated mice also had less DNA damage, higher neuroplasticity, increased production of new neurons from neuronal stem cells, less neuronal damage, and lower rates of death. In the hippocampus area of the brain–in which damage and loss of volume are found in people with dementia–NR seemed to either clear existing DNA damage or prevent it from spreading further.

The NR-treated mice also performed better than control mice on multiple behavioral and memory tests and in addition showed better muscular and grip strength, higher endurance, and improved gait compared with their control counterparts. The research team believes that these physical and cognitive benefits are due to a rejuvenating effect NR had on stem cells in both muscle and brain tissue.

The research team plans further studies on the underlying mechanisms and preparations toward intervention in humans. (NIH authors: Y. Hou, S. Lautrup, S. Cordonnier, Y. Wang, D.L. Croteau, E. Zavala, Y. Zhang, K. Moritoh, J.F. O’Connell, B.A. Baptiste, M.P. Mattson, and V.A. Bohr, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A DOI:10.1073/pnas.1718819115)

NINDS: STARLIKE CELLS MAY HELP THE BRAIN TUNE BREATHING RHYTHMS

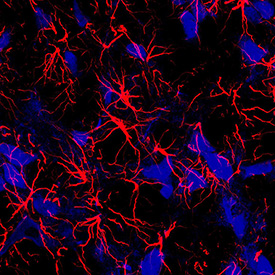

CREDIT: JEFFREY C. SMITH LAB, NINDS

A fresh look at the brain and breathing: An NIH study in rats shows that star-shaped brain cells, called astrocytes (red), may play an active role in breathing.

Traditionally, scientists thought that star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes were steady, quiet supporters of neurons, their talkative, wirelike neighbors. Now, an NIH study suggests that astrocytes may also have their say. It showed that silencing astrocytes in the brain’s breathing center caused rats to breathe at a lower rate and tire out on a treadmill earlier than normal. The scientists tested the role of astrocytes in breathing by genetically modifying the ability of astrocytes in the pre-Bötzinger complex (interneurons essential to respiratory rhythm in mammals) to release transmitters. When the researchers hushed the astrocytes in rats by reducing transmitter release, the rats breathed and sighed at a lower rate than normal. In contrast, if the astrocytes were made chattier by increasing transmission, the rats breathed at higher resting rates and sighed more often. The researchers plan to continue their studies to understand how astrocytes help control other aspects of breathing. (NIH authors: S. Sheikhbahaei and J.C. Smith, Nat Commun 9:article number 370, 2018; DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02723-6)

NEI: EYE COULD PROVIDE “WINDOW TO THE BRAIN” AFTER STROKE

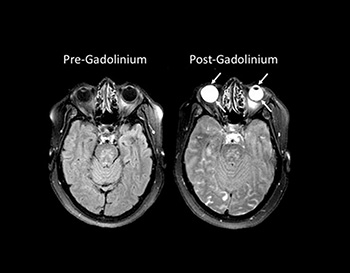

CREDIT: NINDS STROKE BRANCH

Eyes yield information about strokes: MRI scans revealed that a chemical called gadolinium, used to improve images, leaked into the eyes of stroke patients.

Research into curious bright spots in the eyes on stroke patients’ brain images could one day alter the way these individuals are assessed and treated. A team of scientists at NEI found that a chemical routinely given to stroke patients undergoing brain scans can leak into their eyes, highlighting those areas and potentially providing insight into their strokes.

The eyes glowed so brightly on those images due to gadolinium, a usually safe, transparent chemical often given to patients during magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans to highlight abnormalities in the brain. In healthy individuals, gadolinium remains in the bloodstream and is filtered out by the kidneys. However, when someone has experienced damage to the blood–brain barrier, gadolinium leaks into the brain, creating bright spots that mark the location of brain damage. Previous research had shown that certain eye diseases could cause a similar disruption to the blood–ocular barrier, which does for the eye what the blood–brain barrier does for the brain. The NEI team discovered that a stroke can also compromise the blood–ocular barrier and that the gadolinium that leaked into a patient’s eyes could provide information about his or her stroke.

The researchers performed MRI scans on 167 stroke patients upon admission to the hospital without administering gadolinium and compared them with scans taken using gadolinium two hours and 24 hours later. Because gadolinium is transparent, it did not affect patients’ vision and could only be detected with MRI scans. Roughly three-quarters of the patients experienced gadolinium leakage into their eyes on one of the scans, with 66 percent showing it on the two-hour scan and 75 percent on the 24-hour scan. The phenomenon was present in both untreated patients and patients who received a treatment, called tissue plasminogen activator, to dissolve the blood clot responsible for their strokes. The findings raise the possibility that, in the future, clinicians could administer a substance to patients that would collect in the eye just like gadolinium and quickly yield important information about their strokes without the need for an MRI. (NIH authors: E. Hitomi, A.N. Simpkins, M. Luby, L.L. Latour, and R. Leigh, Neurology DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005123)

NIAAA: NIH STUDY SHOWS STEEP INCREASE IN RATE OF ALCOHOL-RELATED ER VISITS

PHOTO CREDIT: MIKE G/THINKSTOCKPHOTOS.COM

Emergency room (ER) visits increased by nearly 50 percent between 2006 and 2014, especially among females and drinkers who are middle-aged or older, according to a new study conducted by NIAAA researchers who analyzed data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (NEDS), the largest ER database in the United States. Although men account for more alcohol-related ER visits than women, the rate of such visits increased more among females than males (5.3 percent versus 4.0 percent annually) over the study period. This increase was driven primarily by a larger increase in the rate of chronic alcohol misuse–related visits for females than males (6.9 percent versus 4.5 percent annually).

Although the current study did not explore specific alcohol and drug combinations, the NEDS data show that other drugs were involved in 14 percent of alcohol-related ER visits. Other drug involvement with alcohol increased the likelihood that an individual would be admitted to the hospital.

Taken together, these findings highlight the growing burden of acute and chronic alcohol misuse on public health and underscore the opportunity for health-care providers to conduct evidence-based interventions, ranging from brief interventions to referral to treatment, during alcohol-related ER visits. (NIH authors: A. White, G. Ng, R. Hingson, and R.Breslow, Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42:352–359, 2018)

NIEHS: HIGH EXPOSURE TO RADIOFREQUENCY RADIATION LINKED TO TUMOR ACTIVITY IN MALE RATS

High exposure to radiofrequency radiation (RFR) in rodents resulted in tumors in tissues surrounding nerves in the hearts of male rats, but not female rats or any mice, according to draft studies from the NIEHS’s National Toxicology Program (NTP). The exposure concentrations used in the studies were equal to and higher than the highest permitted for local tissue exposure in cell-phone emissions today. Cell phones typically emit lower concentrations of RFR than the maximum allowed. NTP will hold an external expert review of its complete findings from these rodent studies March 26–28, 2018. For more information, visit https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/about/org/sep/trpanel/meetings/docs/2018/march/index.html

NIEHS: DEFENDING AGAINST ENVIRONMENTAL STRESSORS MAY SHORTEN LIFESPAN

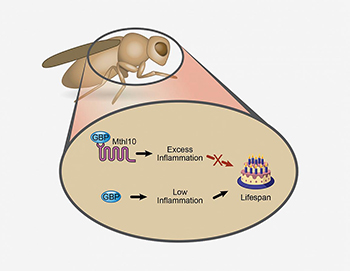

CREDIT: NIEHS

The binding of GBP to Mthl10 promotes inflammation, which decreases the lifespan of a fruit fly. In contrast, the removal of GBP’s binding partner Mthl10 produces less inflammation and increases the lifespan of the fly.

A shorter life may be the price an organism pays for coping with the natural assaults of daily living. NIH scientists and their colleagues in Japan used fruit flies to examine the relationship between lifespan and signaling proteins that defend the body against environmental stressors such as bacterial infections and cold temperatures. Because flies and mammals share some of the same molecular pathways, the work may demonstrate how the environment affects longevity in humans.

The research identified Methuselah-like receptor 10 (Mthl10), a protein that moderates how flies respond to inflammation. The finding provides evidence for one theory of aging, which suggests longevity depends on a delicate balance between proinflammatory proteins, thought to promote aging, and anti-inflammatory proteins, believed to prolong life. These inflammatory factors are influenced by what an organism experiences in its everyday environment.

Mthl10 appears on the surface of insect cells and acts as the binding partner to a signaling molecule known as growth-blocking peptide (GBP). Once Mthl10 and GBP connect, they initiate the production of proinflammatory proteins, which in turn shorten the fly’s life. However, removing the Mthl10 gene makes the flies unable to produce Mthl10 protein and prevents the binding of GBP to cells. As a result, the flies experienced low inflammation and longer lifespans. Fruit flies without Mthl10 live up to 25 percent longer, but they exhibit higher death rates when exposed to environmental stressors, according to the researchers.

The study proposes that the human counterpart to GBP is a protein called defensin beta 2, but the nature of its binding partner is currently unknown. It is not always possible, however, for humans to prevent illness and environmental stress from influencing the level of inflammation they experience.

The study shows that avoiding excess calorie intake, that is, not overindulging in too much carbohydrate and fat, may reduce concentrations of proinflammatory proteins. (NIH authors: E.J. Sung, M.E. Cook, J.W. Putney, G.S. Bird, and S.B. Shears, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114:13786–13791, 2017)

NIEHS: HIGH FAT DIET MAY INCREASE COLON CANCER RISK VIA MICROBIOME

A team of NIEHS researchers found that a high-fat diet consistently altered the collection of microbes residing in mice’s digestive tracts and that this diet-microbe combination causes genes in colon cells to behave more like they would in colon cancer. Moreover, when the group transplanted gut microbes from obese mice on the high-fat diet to lean, germ-free mice, the microbiomes of the germ-free mice came to resemble those of their donors, but only if they were also fed the same high-fat diet. The germ-free mice given microbes from obese mice showed the same changes in cancer-related gene activity as their obese donors when they consumed the same high-fat diet. The scientists now plan to use a mouse model of colon cancer to examine if those diet- and microbiome-related shifts in gene activity truly increase the likelihood of developing cancer. (NIEHS authors: Y. Qin, J.D. Roberts, S.A. Grimm, F.B. Lih, L.J. Deterding, R. Li, K. Chrysovergis, and P.A. Wade. Genome Biol 19:7, 2018; DOI: 10.1186/s13059-018-1389-1)

NEI, NCI, NHGRI: STEM-CELL THERAPY FOR EYE DISEASE CLOSER TO THE CLINIC

Scientists at NEI reported that tiny tubelike protrusions called primary cilia on cells of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) are essential for the survival of the retina’s light-sensing photoreceptors. The discovery has advanced efforts to make stem cell–derived RPE for transplantation into patients with geographic atrophy, otherwise known as dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), a leading cause of blindness in the United States.

In a healthy eye, RPE cells nourish and support photoreceptors, the cells that convert light into electrical signals that travel to the brain via the optic nerve. RPE cells form a layer just behind the photoreceptors. In geographic atrophy, RPE cells die, which causes photoreceptors to degenerate, leading to vision loss.

The researchers are hoping to halt and reverse the progression of geographic atrophy by replacing diseased RPE with lab-made RPE. The approach involves using a patient’s blood cells to generate induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), cells capable of becoming any type of cell in the body. The iPSCs are grown in the laboratory and then coaxed into becoming RPE for surgical implantation.

Attempts to create functional RPE implants, however, have hit a recurring obstacle: iPSCs programmed to become RPE cells frequently fail to mature into functional RPE capable of supporting photoreceptors. In cases where they do mature, however, RPE maturation coincides with the emergence of primary cilia on the iPSC-RPE cells.

The researchers tested three drugs. Two drugs known to enhance cilia growth significantly improved the structural and functional maturation of the iPSC-derived RPE. The third drug, an inhibitor of cilia growth, caused severely disrupted structure and functionality in the cilia.

The report suggests that primary cilia regulate the suppression of the canonical WNT pathway, a cell-signaling pathway involved in embryonic development. Suppression of the WNT pathway during RPE development instructs the cells to stop dividing and to begin differentiating into adult RPE, according to the researchers. The study’s findings have been incorporated into the group’s protocol for making clinical-grade iPSC-derived RPE. They will also inform the development of disease models for research of AMD and other degenerative retinal diseases, Bharti said. (NIH authors: Q. Wan, B.S. Jha, J. Hartford, V. Khristov, R. Dejene, J. Chang, Q. Lu, J. Silver, C. Insinna-Kettenhofen, D. Patel, M. Lotfi, M. Malicdan, N. Hotaling, A. Maminishkis, B. Brooks, K. Miyagishima, M. Gunay-Aygun, C. Westlake, S. Miller, R. Sharma, and K. Bharti, Cell Rep 22:189–205, 2018)

NIAID, CC: MERS ANTIBODIES PRODUCED IN CATTLE SAFE; TREATMENT WELL TOLERATED IN PHASE 1 TRIAL

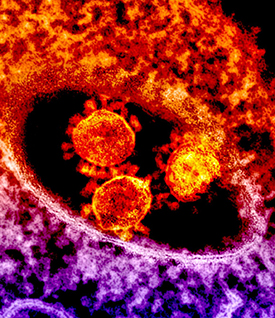

CREDIT: NIAID

The round, spiked objects at center are MERS coronavirus particles.

An experimental treatment developed from cattle plasma for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus infection shows broad potential, according to a small clinical trial led by NIH scientists and their colleagues. The treatment, SAB-301, was safe and well tolerated by healthy volunteers, with only minor reactions documented.

The first confirmed case of MERS was reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012. Since then, the MERS coronavirus has spread to 27 countries and sickened more than 2,000 people, of whom about 35 percent have died, according to the World Health Organization. There are no licensed treatments for MERS. SAB-301 was developed by SAB Biotherapeutics of Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and has been successfully tested in mice. The treatment comes from so-called “transchromosomic cattle.” These cattle have genes that have been slightly altered to enable them to produce fully human antibodies instead of cow antibodies against killed microbes with which they have been vaccinated—in this case the MERS virus. The clinical trial, conducted by NIAID, took place at the NIH Clinical Center. In the study, 28 healthy volunteers were treated with SAB-301 and 10 received a placebo. Six groups of volunteers given different intravenous doses were assessed six times over 90 days. Complaints among the treatment and placebo groups—such as headache and common cold symptoms—were similar and generally mild.

The researchers believe they may be able to use transchromosomic cattle to rapidly produce human antibodies against other human pathogens as well, in as few as three months. This means they could conceivably develop antibody treatments against a variety of infectious diseases in a much faster time frame and in much greater volume than currently possible. [NIH authors: J.H. Beigel, J. Voell, P. Kumar, K. Raviprakash, H. Wu, J.-A. Jiao, E. Sullivan, T. Luke, and R.T. Davey Jr., Lancet Infect Dis DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30002-1)].

NIAID, CC: NIH STUDY SUPPORTS USE OF SHORT-TERM HIV TREATMENT INTERRUPTION IN CLINICAL TRIALS

A short-term pause in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatment during a carefully monitored clinical trial neither led to lasting expansion of the HIV reservoir nor caused irreversible damage to the immune system, new findings suggest. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) benefits the health of people living with HIV, prolongs their lives, and prevents transmission of the virus to others. If taken daily as directed, ART can reduce viral load to amounts that are undetectable with standard tests. However, the virus remains dormant in a small number of immune cells, and people living with HIV must take ART daily to keep the virus suppressed. If a person with ART-suppressed HIV stops taking medication, viral load will almost invariably rebound to high concentrations.

Researchers are working to develop therapeutic strategies to induce sustained ART-free remission. Clinical trials to assess the efficacy of such experimental therapies may require participants to temporarily stop taking ART, an approach known as analytical treatment interruption, or ATI.

In the current study, researchers at the NIAID analyzed blood samples from 10 volunteers who had participated in a clinical trial evaluating whether infusions of a broadly neutralizing antibody could control HIV in the absence of ART. During the trial, participants temporarily stopped taking ART. The 10 participants subsequently experienced viral rebound and resumed ART 22 to 115 days after stopping. While treatment was paused, the participants’ HIV reservoirs expanded along with increases in viral load, and researchers observed abnormalities in the participants’ immune cells. However, six to 12 months after the participants resumed ART, the size of the HIV reservoirs and the immune parameters returned to values observed prior to ATI.

The findings support the use of ATI in clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of therapeutic strategies aimed at achieving sustained ART-free remission, the authors conclude. However, larger studies that do not involve any interventional drugs are needed to confirm and expand on these results. The NIAID investigators currently are conducting a clinical trial to monitor the impacts of short-term ATI on a variety of immunologic and virologic parameters in people living with HIV. (NIH authors: K.E. Clarridge, J. Blazkova, M. Petrone, E.W. Refsland, J.S. Justement, V. Shi, E.D. Huiting, C.A. Seamon, S. Moir, M.C. Sneller, and T.-W. Chun, PLOS Pathog DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1006792)

NIAID: FLU-INFECTION STUDY INCREASES UNDERSTANDING OF NATURAL IMMUNITY

CREDIT: NIH

3-D print of hemagglutinin (HA), one of the proteins found on the surface of influenza virus that enables the virus to infect human cells. In this model, blue and purple denote areas where mutations can change the ability of the virus to attach to host cells and cause infection.

A new study by NIAID researchers has found that people with higher concentrations of antibodies against the stem portion of the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) protein have less viral shedding when they get the flu, but do not have fewer or less-severe signs of illness. HA sits on the surface of the influenza virus to help bind it to cells and features a head and a stem region. Scientists only recently discovered that humans naturally generate anti-HA-stem antibodies in response to flu infection, and this study is the first of its kind to evaluate pre-existing concentrations of these specific antibodies as a predictor of protection against influenza. The findings could have implications for flu-vaccine development, according to the authors.

The study team has explored immune responses to two influenza surface proteins: HA—the main target of traditional seasonal flu vaccines—and neuraminidase (NA). The head region of HA is constantly changing, which is why influenza vaccine strains must be updated each year. The HA-stem region, however, is less susceptible to change, making it a potential target for novel vaccines aimed at broader, more durable protection.

In the new analysis, investigators sought to understand the role of pre-existing anti-HA-stem antibodies in protection against influenza using data from a healthy volunteer influenza challenge trial that took place in 2013 at the NIH Clinical Center. The trial enrolled 65 healthy volunteers aged 18 to 50 years. Participants stayed in a specially designed isolation and infection-control unit throughout the study. Investigators measured participants’ baseline concentrations of anti-HA-stem antibodies, infected them with a 2009 H1N1 influenza virus, and then measured concentrations of anti-HA-stem antibodies again.

They found that all volunteers had anti-HA-stem antibodies at baseline, although values varied, and 64 percent of participants had increased concentrations after infection. However, people with higher values before exposure had smaller increases, suggesting there could be a limit that humans can achieve naturally. Trial investigators also closely monitored participants’ symptoms and the amount of influenza virus they shed from the nose, which may indicate how contagious someone is. Similar to findings regarding anti-HA-head antibodies, they found that participants with higher baseline concentrations of anti-HA-stem antibodies had reduced viral shedding but no significant reduction in the duration or severity of illness.

The results show that people naturally make anti-HA-stem antibodies, but those responses vary significantly, and also these antibody concentrations are not independent predictors of whether someone becomes sick or if so, how severely. The authors note that antibodies against NA remain the only identified predictor of disease severity, according to previously reported trial data. Although the data are limited, the results have implications for novel influenza-vaccine design, according to the authors. They note future strategies ideally should focus on more than one aspect of immunity. “Careful consideration of the complexity of influenza immune protection and evaluation of all aspects of the anti-influenza immune responses will ultimately be necessary in the development of a successful broadly protective or universal influenza vaccine,” the authors said. (NIH authors: J.K. Park, A. Han, L. Czajkowski, S. Reed, R. Athota, T. Bristol, L.A. Rosas, A. Cervantes-Medina, J.K. Taubenberger, and M.J. Memoli, MBio 9:pii:e02284-17, 2018)

NICHD: INDUCED LABOR AFTER 39 WEEKS MAY REDUCE NEED FOR C-SECTION

Healthy first-time mothers whose labor was induced in the 39th week of pregnancy were less likely to have a cesarean delivery than those in a similar group who were not electively induced at 39 weeks, according to a study by the NICHD researchers. Women in the induced group were also less likely to experience pregnancy-related blood-pressure disorders, such as pre-eclampsia, and their infants were less likely to need help breathing in the first three days. The average length of a pregnancy is 40 weeks.

Current guidelines recommend against elective induction of labor in women in their first pregnancy prior to 41 weeks because of concern of increased need for cesarean delivery. Elective induction at 39 weeks, however, has become more common in recent years.

More than 6,100 first-time mothers in the NICHD Maternal Fetal Medicine Units Network were randomly assigned to induced labor or to expectant management. Cesarean delivery was less frequent in the induced-labor group (19 percent) versus the expectant-management group (22 percent). Pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension occurred in nine percent of the induced group and 14 percent of the expectant-management group. Among newborns, three percent of those whose mothers were in the induced group needed respiratory support, compared with four percent whose mothers were in the expectant-management group. (NIH author: W. Grobman, Am J Obstet Gynecol 218:S601, 2018)

NIAID: EBOLA VIRUS INFECTS REPRODUCTIVE ORGANS IN MONKEYS

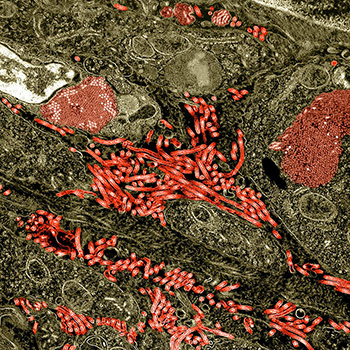

CREDIT: NIAID

Colorized transmission-electron micrograph of the ovary from a nonhuman primate infected with Ebola virus. Characteristic filamentous Ebola virus particles are present between cells (bright red). Intracytoplasmic Ebola virus inclusion bodies forming crystalline arrays can be seen within ovarian stromal cells (darker red).

Ebola virus can infect the reproductive organs of male and female macaques, according to a study published by NIAID scientists. The findings suggest that that humans could be similarly infected. Prior studies of survivors of the 2014–2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa revealed sexual transmission of Ebola virus and also showed that viral RNA (Ebola virus genetic material) can persist in semen after recovery. While little is known about viral persistence in female reproductive tissues, pregnant women with Ebola virus disease have a maternal death rate of more than 80 percent and a fetal death rate of nearly 100 percent.

Based on the findings, the authors hypothesize that Ebola virus can persist in reproductive organs in human survivors, and that the virus may reach seminal fluid in men by infecting immune cells called tissue macrophages. However, it is unclear whether the detection of Ebola virus RNA in semen documented in human studies means that infectious virus is present. The authors note that additional research is needed. (NIH authors: D.L. Perry, L.M. Huzella, J.G. Bernbaum, P.B. Jahrling, K.R. Hagen, and R.F. Johnson, Am J Path 188:550–558, 2018; DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.11.004)

This page was last updated on Saturday, January 18, 2025