Going the Distance

Teresa Przytycka: Driven by Curiosity and Big Dreams

If you ask computational biologist Teresa Przytycka where she’s from, and she’s likely to quip, “Do you mean geographically or scientifically?”

Both answers cover long distances for her. Her journey, which began in Poland many years ago, has brought her to NIH where she’s a senior investigator in the National Library of Medicine’s National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

CREDIT: BILL BRANSON

The geographical journey

Przytycka was born and raised in Myszków, Poland, a small city with three factories surrounded by a rural area. Although her parents were educated, they “came from a village where…people typically ended their education at basic reading and writing skills,” she said. “In fact, since they grew up during the war, a good chunk of my parents’ schooling was within the Polish underground education system—very brave but not very rigorous.”

Despite growing up under unassuming circumstances, Przytycka considers herself fortunate. She was lucky enough to have a group of curious friends in school. “I think we inspired each other in dreaming big,” she said.

Her curiosity and big dreams have stayed with her.

She studied at the University of Warsaw (Warsaw, Poland), earning a master’s degree in mathematics with a concentration in computer science. “The department of mathematics wasn’t infiltrated by the Communist Party,” Przytycka said. “And thus [it] was an enclave of anticommunist opposition.”

After graduating, she stayed at the university, working as a research and teaching assistant in the Department of Mathematics, Mechanics, and Informatics. It was there she met her husband, Jozef, who had a Ph.D. in mathematics from Columbia University (New York). Shortly after they married, Jozef was offered a postdoctoral position at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, Canada.

So she applied to a Ph.D. program in computer science at the same university. Again, Przytycka felt fortunate—UBC accepted her. Plus, she was accepted without having to take an English test.

“One of the faculty members, a Slovak professor, recognized the names of some of the mathematicians who taught me [from] the so-called ‘Polish School of Mathematics,’ [which] had international recognition,” she explained. “UBC had faith in me.”

It was only after arriving in Vancouver that Przytycka had to take English exams. Even though she hadn’t taken English in school, her knowledge of German and a friendship with an American journalist proved to be helpful.

“The journalist wanted to learn about life under communism, so we spent lots of time together,” she said. “I was a member of ‘Solidarity’—an underground anticommunist movement. Sometimes, I helped translate texts from underground newspapers for her.”

Przytycka planned to get her Ph.D. and return to the University of Warsaw. But by the time she had earned her degree in computer science in 1990, she also had two sons—a toddler and an infant. She decided not to go back to Poland after all. She knew she wouldn’t be able to work because there was a “lack of support for children this young and social pressure to be a stay-at-home mom [and] very few day-care centers,” she said.

With her two boys in tow, she chased down opportunities in the departments of computer science at University of Southern Denmark at Odense (Odense, Denmark) and the University of California, Riverside. Her husband followed when he could, but often she was on her own with the children.

She was also many times the only female member of the computer-science faculty. She remembers receiving an invitation to a faculty barbecue that read, “Wives are welcome.” She joked, “Can Jozef come?” But most of the time she says she didn’t think very much about being the only woman (and later one of two) in the department.

The beginnings of a new direction

In the mid-1990s, she told her husband, “Next time you find a position, I’ll follow you.”

Unbeknownst to her at the time, she would be doing more than following her husband. She would be forging a new career.

Teresa Przytycka and her husband collaborate on parenting and a research paper in this 1987 photo taken at the University of British Columbia.

When her husband secured a position at George Washington University (Washington, D.C.), Przytycka, as promised, followed him, starting with a visiting position at the University of Maryland (College Park, Maryland). At the same time, while her research was still focused on the theory of algorithms, she began working on questions that were motivated by biology.

“There were some nice mathematical questions that arise in the context of evolution and other interesting, biologically motivated mathematical problems. How would you construct evolutionary trees? How to measure an agreement between two evolutionary trees constructed with different methods?” she explained. “Those are very mathematical questions, and while they don’t require biological understanding, they started my interest in biology.”

Her interest was piqued even more when she learned from the Notices of American Mathematical Society that the Department of Energy and the Sloan Foundation had announced a new fellowship in computational biology. Before she could apply, she needed to find a mentor in biology. With the help of a computer science colleague, she found one: George Rose, a professor in the Department of Biophysics at the Johns Hopkins University (Baltimore) and a well-known biophysicist working on protein folding. He agreed to be her mentor. “Once again I was fortunate and got the fellowship,” she said.

With this fellowship in hand, she crossed the line from working on computer-science questions that are motivated by biology to biological questions that require computer science.

The road to NCBI

A few years later, in 2003, she was hired as a principal investigator at NCBI. Not only was it a dream position scientifically, but hers and Jozef’s “two-body” problem—two researchers trying to find jobs in the same geographical area—was finally solved.

She was officially working toward a career in biology. This still seems to startle her. “I never really liked biology in school. It wasn’t quantitative then,” Przytycka said. “Biology has changed. It became mathematical, more quantitative, and, from my perspective, far more exciting.”

Perhaps biology became more like Przytycka.

“It was fortunate for me that this trend started when I was at a point in my career when I was open to a big change,” she said. “It’s fair to say that I was amongst the first group of computer scientists that made their way to biology.”

Through the years, she has built her team of men and women thoughtfully—albeit unconventionally.

“Often people come to my group without any knowledge of biology,” Przytycka said. “You are well-served if people in your group are strong in computer science, and since this is the field where I’m coming from, it’s easier for me to work with people who think mathematically. I am able to see where their strengths are and can help them navigate biology, so they can direct their talents toward solving biological questions.”

Currently her team, named the Algorithmic Methods in Computational and Systems Biology group, consists of two staff scientists, two postdoctoral fellows, one post-baccalaureate, and one research fellow. “This is a very strong and dedicated group,” she said with pride. “We are trying to lead in developing new methods and new ways of looking at data.”

Three areas

Przytycka’s team works in three basic areas: cancer and diseases, gene regulation, and algorithms for the efficient utilization of large datasets.

In the context of disease studies, her group develops computational methods advancing systems-level understanding of cancer, the emergence of complex phenotypes, and the detection of causal genetic mutations and their interactions. “It’s computational and data driven. It often calls for development of new methods and algorithms,” she said. “This suits me very well coming from computer science.”

As for gene regulation, she collaborates with Brian Oliver’s group (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Diseases) to work on fruit flies and is developing methods for constructing condition-specific regulatory networks. In addition, in collaboration with another experimentalist, David Levens at the National Cancer Institute’s Center for Cancer Research, she studies non-B DNA structures (a conformation alternative to the canonical Watson-Crick B DNA structure) and their role in gene regulation, mutagenesis, and diseases.

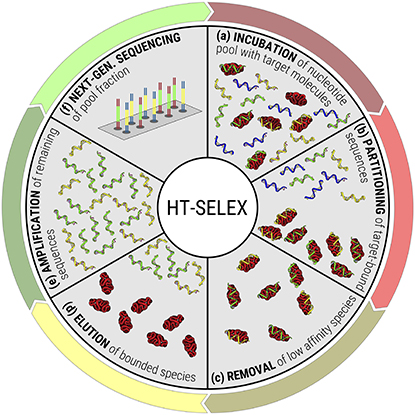

CREDIT: JAN HOINKA, NIBIB

Schematic of one selection cycle of HT-SELEX (high-throughput systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment), which is used to identify aptamers.

The third area relates to analysis of big data. For example, they developed novel clustering and motif-finding algorithms. Her team developed a software tool called AptaTRACE that could help drug developers and scientists identify molecules that bind with high precision to targets of interest.

“This research is an excellent example of how the benefits of ‘big data’ critically depend upon the existence of algorithms that are capable of transforming such data into information,” she said.

Driven by curiosity

Whatever she’s working on, Przytycka appreciates the opportunities at NIH.

“Researchwise, I’m working on a large spectrum of problems. I think that working for NIH particularly helps me do that,” she explained. “First, I am surrounded by experts working on diverse biological inquiries. Exposure to this variety of biological questions and the realization that they can be helped with novel computational methods makes it is hard to resist and not give them a try.”

For this mathematician computer scientist who works in biology, curiosity is a large part of what drives her. And when that curiosity can be helped with an elegant computational algorithm, this is the best combination.

This article was adapted from one that appeared in NLM In Focus: https://infocus.nlm.nih.gov/2017/02/06/teresa-przytycka-goes-the-distance.

This page was last updated on Monday, April 11, 2022