The Stadtman Legacy

Trans-NIH Recruiting Effort Brings in Nine Investigators

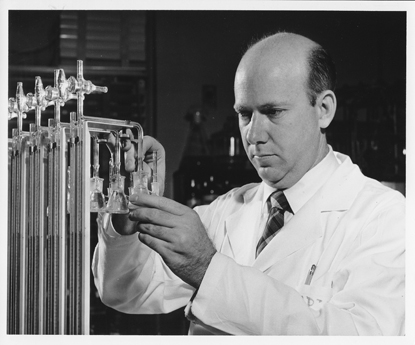

COURTESY OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY

The NIH-wide recruiting program for intramural scientists was named for legendary NIH investigator Earl Stadtman (above, in 1952) who died in 2008.

NIH welcomes the 2010-2011 class of Earl Stadtman Investigators, named for the legendary biochemist who worked at NIH for 50 years. Stadtman mentored and inspired countless researchers including two who went on to become Nobel laureates—Michael Brown and Stanley Prusiner—and others who were later elected to the National Academy of Sciences. The Stadtman program, launched in 2009, a year after his death, aims to attract outstanding scientists whose research areas are not restricted to the interests of particular institutes but span the biomedical fields.

Ordinarily, searches for intramural scientists are conducted by individual institutes and centers (ICs). The Stadtman program, however, is a combined recruiting effort whereby the ICs share the cost as well as provide review committee members. The recruits’ proposed projects must be innovative, represent a broad range of scientific expertise, and have the potential to yield high-impact results. The Stadtman investigators are offered competitive salaries, research space, resources, supported positions, an operating budget, and access to cutting-edge technologies.

In 2009, more than 800 people applied and eight were hired (see the article in the March-April 2011 issue of the NIH Catalyst at http://www.nih.gov/catalyst/2011/11.04.01/catalyst_v19i2.pdf). In 2010-2011, fewer people applied. Still, out of 563 applicants, nine exceptionally qualified scientists were hired into the Stadtman program. The following is a synopsis of who they are and why they are excited to be at NIH.

Daniel Barber (NIAID)

Immunologist Daniel Barber had his first taste of NIH before he ever started working on his Ph.D. at Emory University (Atlanta): He was a predoctoral fellow in the lab of NIAID scientist Ronald Schwartz. After completing his degree—and making the significant discovery that blocking the programmed cell death protein–1 (PD-1) pathway could boost T-cell function and enhance control of an established viral infection—Barber returned to NIAID in 2006 as a research fellow in Alan Sher’s lab. There, he explored the role of PD-1 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and on the mechanisms of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, observed in patients recovering from immunodeficiency. In 2012, he was hired as an Earl Stadtman investigator and chief of the T Lymphocyte Biology Unit in NIAID’s Laboratory of Parasitic Diseases, where he’ll be continuing the work he started in Sher’s lab.

“I knew that [NIH] is a place where I can thrive,” he said of his decision to apply to the Stadtman program. “The NIAID intramural program has fantastic high-containment laboratory resources that I need to develop a strong research program in the immunology of M. tuberculosis infection.”

Susan Harbison (NHLBI)

What do aerospace engineering, genetics, and neuroscience have in common? They’re all interests of NHLBI Stadtman investigator Susan Harbison, who graduated with a B.S. in aerospace engineering and a Ph.D. in genetics from North Carolina State University (Raleigh) and did postdoctoral research in neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia) and in genetics at N.C. State. “I’ve always been interested in how things work, from understanding how aircraft fly to solving the mystery of why we sleep,” said Harbison. “When I was a child I used to take small appliances apart [until] my father started bringing broken machines home for me to play with.”

Before joining NHLBI’s Laboratory of Systems Genetics, she was a postdoctoral research scholar at N.C. State. There she was applying high-throughput genomic technologies to study sleep in fruit flies, which share many characteristics relevant to sleep in mammals. At NIH, her “goal is to understand the purpose of sleep and derive computational models describing how gene networks influence sleep.”

She was attracted to NIH because it “has a talented group of scientists doing groundbreaking research on a diverse array of research questions,” she said. “Scientists [in] different disciplines are free to share ideas and collaborate, leading to exceptional possibilities for research.

Bobby Hogg (NHLBI)

“I knew that coming to the NIH would allow me to focus on my science in an environment with tremendous colleagues and resources,” said Bobby Hogg, in NHLBI’s Laboratory of Ribonucleoprotein Biochemistry. With a geologist for a father, Hogg grew up with science as a part of daily life. He earned his Ph.D. in molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley, and used novel biochemical approaches to study ribonucleoprotein complexes that contain noncoding RNAs. During his postdoctoral training at Columbia University (New York), he found that the regulator of nonsense transcripts–1 protein (Upf1), important in the nonsense-mediated messenger RNA (mRNA) decay pathway, selected specific RNAs for degradation by sensing the length of certain untranslated regions. At NIH he is continuing to work on the mechanisms of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay to see how the pathway targets certain mRNAs for degradation while leaving most mRNAs untouched.

Jadranka Loncarek (NCI)

“I have always been fascinated by Old-World scientists and thinkers who, endowed [with] curiosity, [the] power of observation, and [the] humble devices available at their time, discovered the most important principles,” said Jadranka Loncarek in the NCI/Frederick National Laboratory of Cancer Research’s Laboratory of Protein Dynamics and Signaling. “Imagine what more [we] could uncover with the technologies available nowadays.”

Loncarek was drawn to NIH partly because she wanted access to such technologies—she combines state-of-the-art molecular biochemical methods with sophisticated microscopy and laser-microsurgery techniques to investigate cellular processes—as well as the opportunity to interact with hundreds of scientists from different disciplines. She obtained her Ph.D. in cell and molecular biology from the University of Zagreb (Zagreb, Croatia) and did a postdoctoral fellowship at the New York State Department of Health’s Wadsworth Center (Albany, N.Y.), where she examined the mechanisms of cell division. Since her arrival at NIH in 2011, she has been studying the maintenance of centrosomes in proliferating cells. “Centrosomes and their internal organizers—the centrioles—are pivotal for proper development, optimal function of various organs, and genomic stability,” she explained. “There are numerous disorders related to anomalous centrosomes, and almost every type of cancer has too many of them.”

Wei Lu (NINDS)

Wei Lu, a Stadtman investigator in NINDS’s Synapse and Neural Circuit Research Unit, uses genetic tools, electrophysiology, molecular biology, and behavioral assays to decipher the brain’s molecular and systems-level synaptic mechanisms. While earning a Ph.D. in neuroscience and physiology from New York University School of Medicine (New York), he focused on the biochemical characterization of neuronal glutamate receptors and their interacting proteins. Then he did postdoctoral training in neuroscience at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). At UCSF, he combined electrophysiological and single-cell genetic approaches to study excitatory synaptic transmission in rodents. Lu, who was attracted to NIH because of its reputation as “a premier research institute with a long history of excellence in many fields of biomedical research,” attributes his early interest in science to the influence of his parents, who were both science teachers.

Zhiyong Lu (NCBI)

Bioinformatician Zhiyong Lu is developing computational methods and tools for text-mining research (analyzing natural language data) of biomedical text such as that in journal articles. His research group at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) applies text-mining research to improve biomedical literature retrieval and Web access to consumer health information, assist in the curation of biological databases, and predict new uses of existing drugs. He completed a Ph.D. in bioinformatics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine (Denver), before joining NCBI in 2007 as a staff scientist. He became an associate investigator in 2009 and was hired as a Stadtman investigator in 2011. “Working at NCBI gives me unique opportunities to develop and apply my research in text mining to real-world problems and contribute to improved information access for biomedical scientists and online health consumers worldwide,” he said. His recent research has been integrated into and widely used in PubMed and other NCBI databases. Lu also co-organizes international scientific conferences and workshops such as BioCreative, an international community-wide effort for evaluating text mining and information-extraction systems applied to the biomedical domain.

Philip Shaw (NHGRI)

Philip Shaw, who heads NHGRI’S Section on Neurobehavioral Clinical Research, uses tools from neuroscience, behavioral science, and social science to explore the clinical course of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He obtained his Ph.D. in psychological medicine from the University of London and trained at several hospitals in London and one in Sydney, Australia, before coming to NIH in 2004 as a clinical research fellow (he later served as a staff clinician) in NIMH’s Child Psychiatry Branch. In 2011, he became an Earl Stadtman investigator in NHGRI’s Social and Behavioral Research Branch. His research has shown that, in children with ADHD, the subtle differences in the brain cortex and in the trajectories of brain development might explain why some children with ADHD outgrow their problems. He hopes that understanding this recovery process will lead to novel treatments as well as to the development of tools that will predict the clinical outcome of children with ADHD.

“This research requires us to follow children for many years, and the intramural program is ideal for this type of longitudinal study,” he said. “I want to look at how . . . environmental and genetic factors act together to determine brain development in children.” Shaw is also a member of the Consulting and Liaison Psychiatry Service to the Clinical Center.

Jinfang “Jeff” Zhu (NIAID)

Jinfang “Jeff” Zhu first came to NIH in 1998 as a visiting fellow in NIAID after earning a Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology from the Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry in China. From the beginning he was determined to have his own lab at NIH. He became a staff scientist in 2002, and even when opportunities to become a principal investigator at NIH were limited, he kept turning down invitations to be considered for faculty positions at universities. “I firmly believed that I should remain at NIH and that I would do better science as a staff scientist . . . than as a principal investigator at a university at this early stage of my career,” he said. His determination—he calls it stubbornness—paid off when he was selected as an Earl Stadtman investigator in 2011.

During his Ph.D. training, Zhu worked on signal-transduction pathways in T cells triggered by the important cytokine, interleukin-2 (IL-2). Today, in NIAID’s Laboratory of Immunology, he is studying the diversity and plasticity of T helper cells that are regulated by transcriptional regulatory networks. He is also investigating the functions of key transcription factors in dendritic cells, innate lymphoid cells, and B cells to gain insights into immune responses.

Nihal Altan-Bonnet (NHLBI)

“I always wanted to be a detective,” said , an assistant professor and interdisciplinary researcher in biological sciences at Rutgers University (Newark, N.J.), who will be joining NHLBI’s Cell Biology Center in July 2013. By high school, however, she realized that detective skills could help “solve the puzzles in nature” as well as crimes. She completed her Ph.D. in cellular biophysics at Rockefeller University (New York) and then trained with Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz in NICHD. She went on to Rutgers, where she studied molecular blueprints of host-cell membranes used for viral replication and identified key lipid components that may be potential therapeutic targets. At NHLBI, she will continue to use her sleuthing skills to identify the molecular signatures of membranes that viruses use for replication as well as unlock the mysteries of how cells work in general.

“One of the attractions of NIH is that it will allow an interdisciplinary researcher like myself the resources to try out new ideas or test a risky hypothesis,” she said.

PHOTO BY: BILL BRANSON

Earl Stadtman (above in 1990s) would have loved to mentor the Stadtman investigators who have recently joined NIH. Jeff Zhu (NIAID), Philip Shaw (NIMH/NHGRI), Zhiyong Lu (NCBI), Wei Lu (NINDS), Jadranka Loncarek (NCI), Bobby Hogg (NHLBI), Susan Harbison (NHLBI), Daniel Barber (NIAID), and Nihal Altan-Bonnet (NHLBI).

For more information on Earl Stadtman, visit https://history.nih.gov/exhibits/stadtman/.

For information on the application process, visit https://irp.nih.gov/careers/trans-nih-scientific-recruitments/earl-stadtman-tenure-track-investigator-recruitment-2012.

This page was last updated on Friday, April 29, 2022