From the Annals of NIH History

The History of NIH in (About) 12 Objects: A Curator’s Chronicle

Lyons Retires, Leaves Historic Legacy

It all started with a bottle of whiskey. Many a morning-after tales begin with such a line, but now we know that line also covers the inception of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), according to Michele Lyons, associate director and curator at the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum.

Lyons shared, how shall we put it, our ol‘ salty origins and other insightful bits of NIH history during her Dec. 11 talk, “The History of NIH in (About) 12 Objects: A Curator’s Chronicle.”

“Objects tell stories—why something was made, when it was made, how it was made, what it was made for, who made it, who invented it, who used it, what they used it for, and what the end result was of their work,” Lyons explained about the objects she showcased. “Sometimes, the stories that the objects in our collection tell are pretty technical scientific and medical discoveries, but they always have a human element as well, because fundamentally, NIH’s history is the story of how people have worked together toward one end.”

Here are the highlights on (about) 12 objects.

1. Green River Whiskey Watch Fob, c. 1908

Green River Whiskey was used onboard U.S. Marine Hospital Service ships from about 1895 as a “medicinal” and kept by the captain under lock and key. “Green River Whiskey was the official whiskey of the United States Marine Hospital Service and the precursor of the establishment of NIH with a Hygienic Laboratory, and really, it describes the state of medicine at that time,” Lyons told the Catalyst. Green River Whiskey was used on the ship to treat every ailment suffered by the sailors.

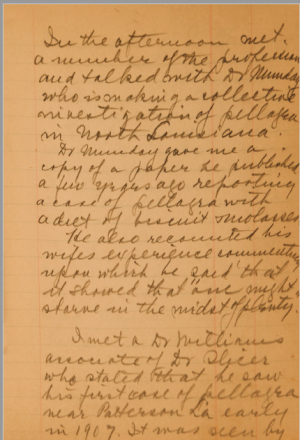

2. Diary of Joseph Goldberger, 1915

Joseph Goldberger conducted a major epidemiological investigation in the American South while studying the cause of pellagra, and discovered its cause was a vitamin B deficiency. His diary is emblematic of the new fields of research pioneered by hygienic laboratory researchers in the early 20th century including air pollution, allergies, and parasitic and infectious diseases—often experimenting on themselves.

3. H. Trendley Dean Dental Collection

Used by H. Trendley Dean, the first NIH dental scientist. Dean became the first director of the National Institute of Dental Research, now NIDCR, in 1948, the same year to which five other NIH institutes can trace their establishment and in which the National Institutes of Health became plural.

4. NIH Multi-Plater, 1963

This multiple Millipore filtration instrument, or multi-plater, was invented at NIH by Philip Leder and Charles Byrne, and used by two NIH Nobel laureates, Marshall Nirenberg and Martin Rodbell. Nirenberg was honored for deciphering the genetic code, and Rodbell for discovering signal transduction in cells. Genetics and cell biology would never be the same.

5. Braunwald-Morrow Mitral Heart Valve, 1959

Designed by Nina Braunwald and Andrew Morrow at NIH, it was used in the first successful mitral valve replacement in a human on March 11, 1960. The little valve invokes NHLBI’s fruitful cardiology program as well as how clinician researchers at the NIH Clinical Center help to set national standards.

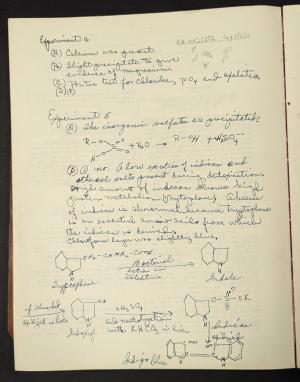

6. Lab Manual of Biological Chemistry, 1950

This textbook belonged to Glendowlyn Young-Cooper, a Black woman who worked in the Laboratory of Immunology, NIAID. It’s a symbol of the history of women, people of color, immigrants, and religious minorities at the NIH, and Lyons called for more such donations.

7. CRAY X-MP/22 Supercomputer, 1985

This computer was used between 1986–1992 at the NIH’s Laboratory of Mathematical Biology in NCI’s Advanced Scientific Computing Laboratory. It has the distinction of being the first supercomputer dedicated solely to biomedical research. There was no need for Lyons to stress the importance of computerization to biomedical research.

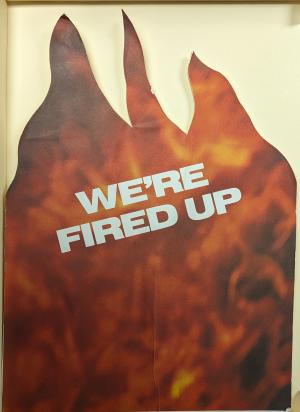

8. “We’re Fired Up” ACT-UP Placard, 1990

Dropped by an AIDS activist at the largest AIDS demonstration on the NIH campus on May 21, 1990. The demonstration helped spur the inclusion of patients and their families on clinical research advisory boards, now a common policy.

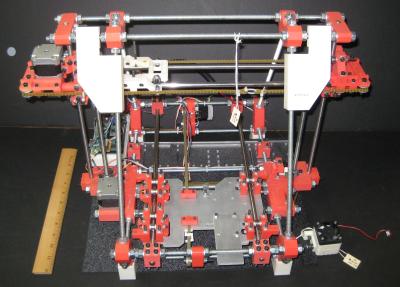

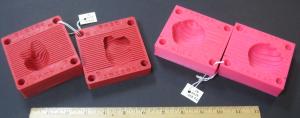

9. 3D-Printer and 3D-Printed Prostate Mold, 2008

This 3D printer was built by Marcelino Bernardo as part of his work on matching prostate cancers to MRI information in 3D printed molds.

10. GenScript Ni-Charged MagBeads

Lyons showed a selection of objects related to the COVID-19 pandemic, which she called “NIH’s finest hour.” These magnetic beads were used in NCI’s Protein Expression Laboratory to purify large quantities of SARS-CoV-2 proteins for research.

11. Aerosol Chamber, 2020

Adriaan Bax’s NIDDK laboratory began studies on the aerosol transmission of SARS-CoV-2 very early in the pandemic. They built their own experimental chambers, like this one from a recycling bin, which became more elaborate as their experiments continued.

12. Barney Graham Bobblehead, 2022

Before Barney Graham retired from the NIAID Vaccine Research Center in 2021, he played a pivotal role in the development of mRNA vaccines, in particular for COVID-19 and Zika. During the pandemic, NIH staff were depicted in popular culture in many ways.

+1. You, today

Lyons wants every NIH employee to understand that we each are making history every day. She described the “Power of One.”

“The power of one person, one problem, one disease, one outbreak, or one condition can spur new knowledge and whole new fields of research; and the power of one legislative act, like the one in 1947 that established the NIH Clinical Center,” she said.

“I want people to give the NIH History Office and Stetten Museum the instruments and devices they are using now,” she continued. “People don't think about themselves as ‘history’ but even if you are not inventing an instrument and are just using something that is common, that’s important, too.” Lyons said the museum has a lengthy wish list, so feel free to reach out and see if you can check any items off their list.

Lyons retired with the close of the 2023 calendar year. In her final remarks at the lecture, she thanked those who have donated items to the History Office over the years.

“Thank you for saving our nation’s legacy, for thinking ahead about what future people will want or need to know, and for just loving history,” she said.

The same could be said of her.

Visit https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=53816 to watch the presentation...and learn

12 things about Lyons, too.

All photos courtesy of the Office of NIH History and Stetten Museum.

This page was last updated on Saturday, November 23, 2024