A Life Collected

Joseph Edward Rall (1920–2008)

When Joseph “Ed” Rall’s daughter, Priscilla Rall, decided to share her father’s history with the NIH Stetten Museum and the National Library of Medicine (NLM), she welcomed representatives from both to her home and amazed them with her family’s extensive historical collections. Pia Rall had painstakingly collected, organized, and preserved the evidence of her father’s life and work—his legacy—and was interested in returning some of these resources to NIH so that his voice would always be found there. Ed Rall did groundbreaking research on the thyroid, founded one of the world’s leading thyroid centers at NIH, and was an inspirational force in NIH’s intramural program.

HANK GRASSO, OFFICE OF NIH HISTORY

This terra-cotta bas relief of Joseph Edward “Ed” Rall (background) and David Platt Rall (foreground) was created by sculptor Christian Peterson. These brothers each left an impression on biomedical research and NIH. Ed Rall served NIH as the deputy director for intramural research from 1983 to 1991. David Rall was the director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1971–1990) as well as founding director of the National Toxicology Program.

The story of NIH’s efforts to preserve the Rall collection is one of collaboration between the DeWitt Stetten, Jr., Museum of Medical Research (part of the Office of NIH History) and the NLM’s History of Medicine Division. Both entities advance the historical understanding of biomedical research, albeit in different ways. The Stetten Museum collects, preserves, and interprets three-dimensional objects associated with NIH researchers and their contributions to biomedicine. NLM’s History of Medicine Division collects, preserves, and interprets books and other printed materials, images, audiovisuals, and original documents related to the general history of medicine and not just what happened at NIH. Because Rall’s narrative is international in scope, it is important not only to NIH’s history but also to the global history of medicine.

“It is always a pleasure working with our colleagues in the Office of NIH History, and especially so on the Rall collection,” said Jeffrey Reznick, chief of NLM’s History of Medicine Division. “Together, we are ensuring that this unique collection as a whole is both preserved for and accessible to current and future generations of historians and other interested researchers, as well as for educators, students, and the general public, all of whom deserve to know about the record of Dr. Rall’s accomplishments in terms of NIH history as well as the history of medicine overall.”

To capture a complete record of a scientist’s professional contributions and to accurately reflect the how, why, and what of that work, the record must also document, to the extent possible, the scientist’s daily life, the environment in which he or she lived and worked, and his or her worldviews and perspectives.

The Rall collection does just that. The Rall family has donated many three-dimensional objects to the museum including Rall’s stethoscope, slide rules, cameras, typewriter, microscope, Marshall Island radiation field-research notebook, U.S. Army footlocker, 1946 desk photocalendar, tobacco pipe, miniature chess set, NIH lab coat, and some of his awards and medals. The museum’s collection also includes digitized copies of some family photographs and papers. The family has donated archival materials—including correspondence, speeches, notebooks, oral histories, photographs, moving images, recordings, and other documents—to the library.

The collection paints a picture of Ed Rall’s life and accomplishments. He was among the first to apply radioactive isotopes of iodine to the study of thyroid function and the treatment of thyroid diseases. He studied under Raymond Keating, Alexander Albert, and Marschelle Power at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, Minn.), receiving the Van Meter Award in 1950 for his residency work. He then moved to the Memorial-Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York), where he was engaged in the early development of treatments for metastatic thyroid cancer with radioactive iodine and became a key member of the team of radiation physicists and clinicians treating patients.

In 1955, Rall was invited to start the Clinical Endocrinology Branch at the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases (NIAMD), the forebear of the current National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease (NIAMS).

Nell Platt Rall and Edward Everett Rall with their sons, Ed (left) and David. The elder Rall was president of North Central College in Naperville, Illinois. “I arrived in this world in 1920 born in the President’s House…just across from the College Library—a Carnegie Library, of course…School appeared to me to be neither good nor bad except that having to do endless examples of long division…was particularly boring.”

—Recollections or Apologia per Vita sua, 2002

At NIH, Rall assembled an array of scientists from different disciplines to focus on a single endocrine organ, the thyroid. His visionary approach led to the creation of one of the world’s leading centers for basic and clinical thyroid research. In 1957, Rall was one of a group of scientists, under the auspices of the Atomic Energy Commission, that was sent to the Marshall Islands to study the effects of radiation on the inhabitants of the Rongelap and Utirik Islands from a nuclear testing accident. Rall helped to introduce preventative treatment with thyroid hormones to reduce the incidence of thyroid nodules and cancers.

In 1959, Rall was off to the other side of the world, the Soviet Union, as part of an official exchange mission. He and Jack Robbins (an NIDDK scientist who died in 2008) published a famous paper, “Proteins Associated with the Thyroid Hormones,” in 1960, which described their theory that only free thyroid hormone is the active hormone (Physiol Rev 40:415–489, 1960).

Rall was NIAMD‘s scientific director for more than 20 years before becoming NIH’s Deputy Director for Intramural Research (1983–1991), and he transitioned to emeritus status in 1995. His tenure was marked by his wide interdisciplinary interests and involvement with fellows and training programs.

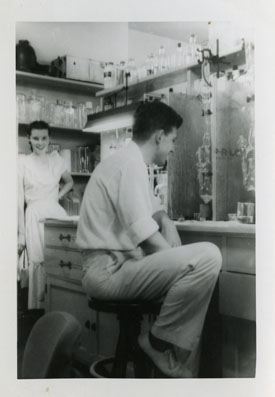

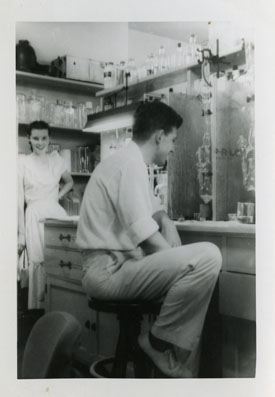

Ed Rall (foreground) and Caroline Domm Rall, whom he met as a child and married in 1944. She had a B.S. in zoology. “[For my Ph.D. degree] I was interested in iodine compounds, and paper chromatography had just come up then. And so I chromatographed blood and serum and urine, looking for the major iodine materials.” —Oral history recorded by Buhm Soon Park, 2000

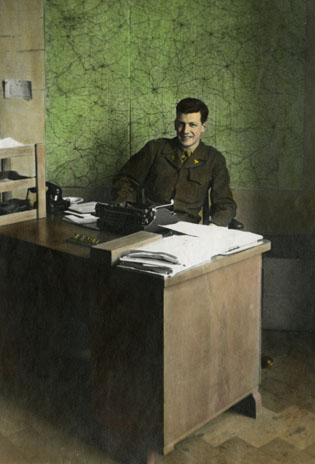

Born in 1920 to North Central College (Naperville, Ill.) president Edward Everett Rall and his wife, Nell Platt Rall, Ed Rall earned his B.S. in zoology from that college in 1941 and his M.S. and M.D. from Northwestern University Medical School (Chicago), now the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis) in 1945 and left for a fellowship at the Mayo Clinic. His wife, Caroline Domm Rall, whom he met as a child and married in 1944, also had a B.S. in zoology. Rall’s residency at the Mayo Clinic was interrupted by a two-year stint in the U.S. Army Medical Corps, where he served at Fort Devens (Ayer and Shirley, Mass.) and at a U.S. Army base in Nürnberg, Germany.

Through the generosity of Priscilla Rall and the Rall family, this unique and valuable collection will be available for researchers of both today and tomorrow, all of whom will be able to read and learn from Ed Rall’s thoughts and perceptions. Quotes mined from his letters and notes will enable Ed Rall himself to narrate the milestones and transitions of his personal and professional life in his own vernacular, personality, and cadence. And museum exhibitions, popular and scholarly press publications, Web-based presentations, curriculum materials, and documentary films that feature his voice will resound with accuracy and authenticity.

To learn more about the Rall collection, contact the Stetten Museum’s Hank Grasso at Hank.Grasso@nih.gov or Michele Lyons at lyonsm@od.nih.gov, or the NLM’s Head of Images and Archives, Rebecca Warlow, at rebecca.warlow@nih.gov.

Ed Rall (foreground) and Caroline Domm Rall, whom he met as a child and married in 1944. She had a B.S. in zoology. “[For my Ph.D. degree] I was interested in iodine compounds, and paper chromatography had just come up then. And so I chromatographed blood and serum and urine, looking for the major iodine materials.”

—Oral history recorded by Buhm Soon Park, 2000

In 1957, Rall was one of a group of scientists that was sent to the Marshall Islands to study the effects of radiation on the inhabitants of the Rongelap and Utirik Islands from a nuclear testing accident. He helped to introduce preventative treatment with thyroid hormones to reduce the incidence of thyroid nodules and cancers. “[The Rongelap people] received about 175 r plus superficial burns from fall out. No one was killed and most of the burns have healed nicely. We examined them for any late effects.” (From: Round-robin letter to extended family, April 30, 1957)

The Rall family has donated many three-dimensional objects to the Stetten museum including Ed Rall’s stethoscope, slide rules, cameras, typewriter, microscope, Marshall Island radiation field-research notebook, U.S. Army footlocker, 1946 desk photocalendar, tobacco pipe, miniature chess set, NIH lab coat, and some of his awards and medals.

The Rall family donated archival materials—including correspondence, speeches, notebooks, oral histories, photographs, moving images, recordings, and other documents—to the National Library of Medicine.

“[A]n early idea before I came here—and this building exemplifies it—is to try and mix them up. That is to say, you’d have a patient wing here, then you’d have the clinical investigator’s laboratories around it, and then in the exterior wing, you’d have basic science. So that way, the clinicians could talk with the basic scientists, who were right next door, and it really worked out well.… And so I think that’s been an important aspect of the NIH, is to make sure that a clinician can talk to a biochemist, a biochemist can talk to an organic chemist, and organic chemist can talk to a chemical physicist, who can talk to a mathematician.… [T]he physical setup of this building encouraged it.” (From: Oral history recorded by Buhm Soon Park, 2000)

“I entered medical school in 1940 and the war began in 1941…I had already started to do research in medical school and I decided that I just would not join the Army…even though about 98 percent of medical students joined…So one day the registrar called me up and said, ‘We did not have any students who are not in the military except for you…do you want a scholarship for your tuition? So I…had a scholarship and two research projects that I got paid for…and then I worked in a hospital at nights. After I graduated medical school, I had this funny inactive commission since 1941. I thought they had forgotten about me because I went through my internship and then went to the Mayo Clinic. Two weeks before I was through that first year at the Mayo Clinic, I received a letter that said report for duty.” —Oral history recorded by Melissa Klein, 1998

“There were five of us visiting on an official exchange mission [from left: DeWitt Stetten, Jr., Rachmiel Levine, Dwight Ingle, Ed Rall, and Edwin ‘Ted’ Astwood]….Were treated with great hospitality and kindness and, I think, frankness. The biology in the USSR is quite different than that of the Western world. In Russia, Pavlov is revered and his experiments repeated endlessly.” (From: Round-robin letter to family, June 8, 1959)

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 27, 2022