2011 Research Festival

Packed with the Best NIH Has to Offer

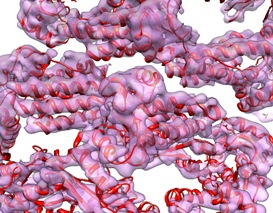

A. Bartesaghi, D. Schauder, S. Subramaniam, NCI

The Research Festival sessions were chock-full of exciting science. In the symposium on dynamic protein assemblies, researchers talked about the challenges of determining how proteins are structured (see page 11). Sriram Subramaniam (NCI) and his colleagues used automated cryo-electron microscopy to obtain high–resolution images of large protein structures such as the GroEL chaperone complex shown above. This density map obtained from cryo-electron microscopy, is superimposed on a structure of the same complex obtained using X-ray crystallography (the thin red spirals).

Once upon a time—in September 1986—the NIH Intramural Research Day was an all-day affair featuring eight talks, 20 workshops, 95 posters, and an evening picnic with jazz musical entertainment on the lawn outside Building 35. Over the years, the event has morphed into a multiday festival. In 2011 the NIH Research Festival featured a plenary session, concurrent symposia sessions with 20 topics and 120 talks, more than 400 posters, special exhibits, a scientific equipment tent show, and more. The picnic, now held at lunchtime, has become a “Taste of Bethesda” event with offerings from area restaurants and entertainment by local musicians.

The idea behind the original NIH Research Day was to “solve the institute silo problem [and] bring people together from all the different institutes and to have them present their work,” said Research Day founder and former Scientific Director Abner Notkins (NIDCR). “There was so much overlapping work going on in different institutes, and often people were not aware of that.”

Notkins also realized that NIH scientists were unlikely to meet researchers outside their own institutes except at “national and international meetings,” he said. It seemed “a little ridiculous, to have to go to Europe to meet people here at the NIH.”

Ernie Branson

Abner Notkins was a scientific director in 1986 in what is now NIDCR when he dreamed up the idea for the first NIH Intramural Research Day. He never would have guessed that in just a few years, the daylong celebration would become a popular week-long event.

Over the quarter-century since the NIH intramural community began setting aside a day to share and celebrate research, the festival has grown in length, breadth, scope, and popularity. But the driving force behind the Research Festival is much the same. “Many of us have little sense of the common ground we share,” said Deputy Director for Intramural Research Michael Gottesman in his introduction to the plenary session. “Bringing everyone together is an opportunity to share that common ground.”

The theme for the 2011 festival, which took place October 24–28, was “how the scientific understanding of human disease can advance our understanding and treatment of those diseases,” said Gary Nabel (VRC), who co-chaired the event with Robert Wiltrout (NCI). “Within that context,” Nabel continued, “we asked the scientists to come forth with the ideas they felt were the most compelling and of greatest interest.” This “grassroots effort” produced sessions on both basic and translational research, showcased work being done at multiple institutes, and highlighted the cutting-edge science being done in the intramural program.

The Research Festival is “packed with the best that NIH has to offer,” NIH Director Francis Collins said in a taped address for the plenary session. Entitled “Molecular Mechanisms of Human Diseases,” the session had a strong translational focus and included research presentations covering immune deficiency diseases, cancers, and neurological disorders.

Pamela Schwartzberg (NHGRI) described her research using model systems to understand the pathogenesis of primary immunodeficiencies. Her lab is studying a severe immune disorder called X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP-1), which is characterized by “a really massive immune disregulation, [which is] often triggered or exacerbated by infection with Epstein Barr virus,” she said. XLP-1 is caused by mutations in the SH2D1A gene, which encodes a small signaling molecule called SLAM-associated protein (SAP). Schwartzberg’s group has developed a SAP-deficient mouse line and has found many molecular and cellular pathways underlying the progression of XLP-1. Her research points the way to potential treatments for XLP-1 and other immune disregulatory diseases.

Kevin Gardner (NCI) studies the molecular linkages between metabolic imbalance, genome stability, and breast cancer. He pointed out that there is a striking statistical correlation between obesity and breast cancer. His lab is studying the COOH-terminal binding protein (CtBP), a molecule that regulates genes such as BRCA, which is critical for protection against breast cancer. Gardner’s research shows that obesity-associated changes in metabolism may cause CtBP to decrease BRCA expression, leading to “a perfect storm” of decreased DNA repair and an increased chance of breast cancer.

Eric Hanson (NIAMS), one of the 2012 winners of the Fellows Award for Research Excellence (FARE), presented a genetics approach to studying NF-kappa-B essential modulator (NEMO) syndrome. NEMO syndrome is a rare immunodeficiency disorder caused by mutations in the IKBKG gene, an essential modulator of NF-kappa-B, an important transcription factor that plays a key role in regulating the immune response to infection. The syndrome can present as a range of disorders from immune deficiency and infectious susceptibility to autoimmunity and inflammatory disease.

Hanson determined that mutations in specific sections of IKBKG lead to changes in the activation state of NF-kappa-B. “We started with the phenotype of the individual and proceeded towards the genotype and then function,” he explained. His work may lead to potential treatments for other inflammatory or immune system disorders.

Dennis Drayna (NIDCD) described how he uses genetics to understand the neuropathology of stuttering. “Stuttering is not a psychological or a social disorder,” said Drayna. “It is a biological disorder with neurologic origins.” Using genetic studies of several large consanguineous families, he found several genes in the lysosomal targeting pathway that when mutated correlate strongly with stuttering. “Mutations in the genes encoding [the] lysosomal targeting pathway appear to account for about 10 percent of familial stuttering” although the connection between the lysosomal targeting pathway and the neurological phenotype is not yet clear. Future studies involving the analysis of vocalizations in genetically altered mice may reveal a molecular and cellular link between these genetic mutations and familial stuttering.

To wrap up the plenary session, Louis Staudt (NCI) talked about locating the Achilles’ Heel of cancer through functional and structural genomics. He uses a genomics approach to study cell survival in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), a heterogeneous mixture of B-cell cancers. Using a library of RNA interference vectors, he found several clusters of genes that are necessary for the proliferation and survival of cancer cells; one of these clusters lies in the B-cell receptor pathway. He presented clinical trials data that demonstrated a potential inhibitor of this pathway. “It’s early,” but the results are sometimes “dramatic.”

Bill Branson

Postdoctoral fellow Percy Pui Sai Tumbale (NIEHS) traveled from North Carolina to discuss her poster on “Structural basis of DNA ligase proofreading by aprataxin with insights into AQA1 neurodegenerative disease” at the Research Festival.

Nabel was pleased that the plenary session was a good start to the festival. “I was struck by the diversity of approaches that were being taken to address specific problems, and the use of animal model systems, the use of human clinical specimens, and the use of structural biology, biochemistry, and all of that, often within the same talk,” he said. The approach of using every available tool to address basic and translational research challenges continued through the remainder of the festival.

After the plenary session ended, attendees dashed from the Masur Auditorium (Building 10) across campus to the Natcher Conference Center (Building 45) to catch the first of four poster sessions and the beginning of four concurrent symposia that would take place over the next several days.

Later in the week, the two-day scientific equipment tent show opened in parking Lot 10H. “The technical sales association exhibits are really a good thing, because you sometimes see a lot of action and interaction and discussions there,” said festival co-chair Wiltrout. “That really suggests that our folks are looking for the best opportunities to apply new technologies that can accelerate their work. I think that’s a vibrant part of the festival.”

Bill Branson

Robert Wiltrout, one of the festival co-chairs and director of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research, helped organize the event.

The true mark of the NIH Research Festival’s success is the collaborations it triggers. But there are no hard data on how many collaborations are sparked by the interactions that take place during festival week. “We should think about polling people after the festival in a formal way [and get] some feedback that we could then use to guide the next festival,” suggested Wiltrout.

Notkins suggested resurrecting an old tradition—having senior investigators, instead of only fellows, present some posters. “It would give our postdocs an opportunity to meet and discuss scientific issues with some of our best-known scientists,” he said.

“I thought [the festival] was a great example of how the NIH takes basic science and capitalizes on it and moves it toward a practical benefit for people,” said Wiltrout.

It was a chance, as Gottesman put it, to “strut our feathers” and display, as we have done each year for the last quarter-century, the unique bench-to-bedside (and sometimes back again) research being done here at the NIH.

This page was last updated on Monday, May 2, 2022