The Autoantibody Hunters

From PANDAS to Long COVID, Defining and Treating Infection-associated Conditions That Aren't So Black and White

BY MICHAEL TABASKO, THE NIH CATALYST

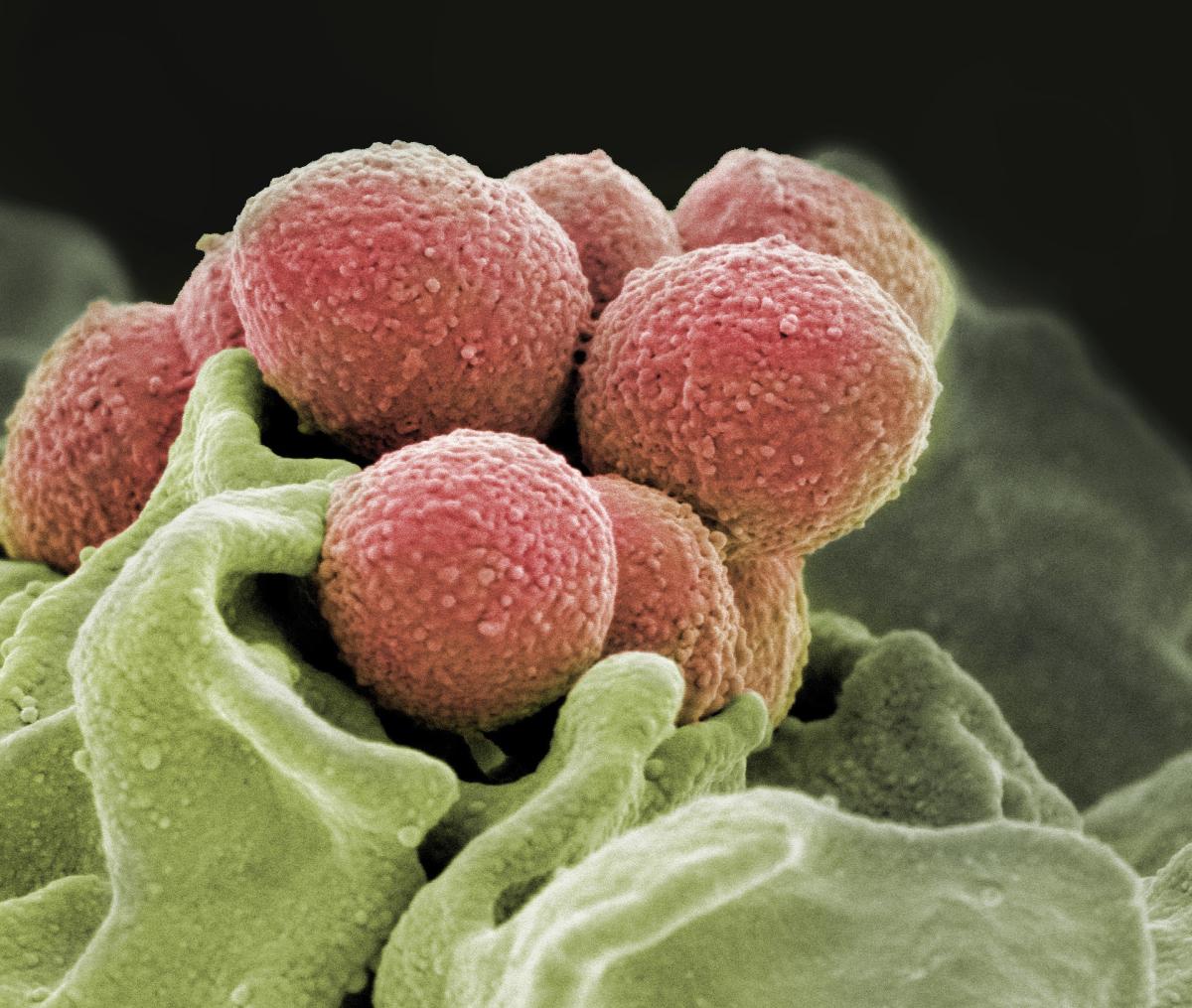

CREDIT: NIAID

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A strep), shown here as pink spheres, may trigger the immune system to create autoantibodies. Pictured is the normal immune response of a neutrophil (green) engulfing the bacterial invader.

The connection between infections and neuropsychiatric conditions can be unsettling, if not downright elusive. Consider a simple bout of strep throat, caused by Streptococcus pyogenes (group A strep), a nearly unavoidable hazard of growing up given the way the illness spreads like wildfire through school-aged kids.

Although the infection is usually treated successfully with antibiotics, it has been reported that some strep-infected children go on to abruptly develop neuropsychiatric symptoms that might include obsessive-compulsive disorder, motor or verbal tics, and other neurological abnormalities. The symptoms may eventually resolve, only to resurface with subsequent infections.

Such is the clinical course of PANDAS, or pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. An unofficial diagnosis is sometimes made in the clinical setting but not without its skeptics (PMID: 30996598).

In 1998, NIMH’s Susan Swedo and her colleagues were the first to establish clinical criteria defining PANDAS (PMID: 9464208). They proposed an autoimmune pathophysiology in which antibodies generated to fight the initial infection were cross-reacting with neural tissue in the basal ganglia, brain regions responsible for behavior and movement. This reaction is a well-studied mechanism known as molecular mimicry whereby microbial proteins that are structurally similar to host proteins result in autoantibodies that target host tissue.

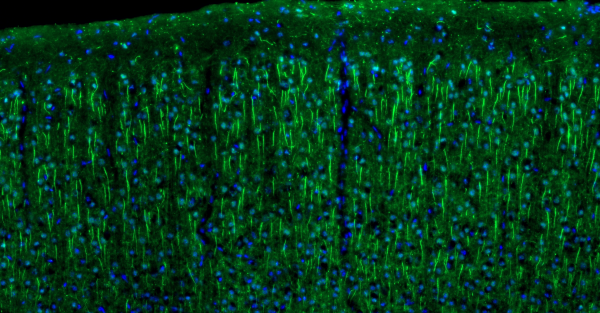

CREDIT: THOMAS NGO, UCSF

Emerging technologies can identify and profile autoantibodies that might underpin some infection-associated conditions. Shown is an immunofluorescence tissue micrograph of autoantibodies (bright green) from the cerebrospinal fluid of a man with HIV who developed steroid-responsive autoimmune meningoencephalitis. The autoantibodies are bound to cortical neurons (nuclei in blue) in mouse brain tissue, and a new tool called phage-display immunoprecipitation sequencing was used to identify the ankyrin G protein as the target of those autoantibodies. Text adapted from the University of California at San Francisco image caption.

Such molecular mimicry has been implicated in Sydenham chorea, a neurologic disorder associated with strep and rheumatic fever (PMID: 24184556), and in Nodding syndrome, in which a parasitic infection appears to give rise to autoantibodies that affect the brain (PMID: 28202777). So, PANDAS does seem to be consistent with other syndromes.

Some critics of the PANDAS hypothesis have pointed to a lack of reproduceable and robust studies validating the underlying mechanisms, diagnostic tests, and the efficacy of therapies, among other concerns. Recognizing these problems, Swedo, who retired from the NIH in 2019, proposed in 2012 the broader pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome, or PANS, which she and her colleagues said modifies the PANDAS criteria to eliminate etiologic factors (DOI: 10.4172/2161-0665.1000113).

The PANDAS-PANS issue is far from settled, but research into this broader connection between infection and neurological abnormalities continues at the NIH, specifically for a constellation of poorly understood infection-associated illnesses, such as long COVID, chronic Lyme disease, and myalgic encephalomyelitis-chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS).

Maybe there's an underlying connection? Below is a snapshot of research investigating this topic, reflecting a new, multi-IC approach that involves a collaboration among NIAID, NINDS, and NIMH.

PANDAS revisited

New tools are at our disposal, and one emerging technology could unearth distinct autoimmune underpinnings of neuropsychiatric conditions. Christopher Bartley, chief of the Translational Immunopsychiatry Unit at NIMH, capitalizes on a new antibody profiling technique called phage display immunoprecipitation sequencing (PhIP-Seq), which identifies the targets of antibodies in biosamples, such as blood or cerebrospinal fluid, to uncover autoantibodies and give a detailed infection history not possible with conventional techniques.

Christopher Bartley

PhIP-Seq uses modified bacteriophage programmed to display any known human or microbial protein in the form of short peptides that invite peptide-antibody interaction within a biosample. Bartley can use PhIP-Seq to precisely identify antibodies that indicate autoimmunity or a prior infection.

“Our library contains over 1.8 million peptides; half encode human proteins; the other half include proteins from over 4,000 microbes and viruses,” said Bartley.

Bartley's team also adapted a technique called luciferase immunoprecipitation system, which was developed by NIDCR’s Peter Burbelo in the early 2000s and measures how much antibody is present in a sample based on light emission, according to an NIDCR report. “It’s incredibly sensitive,” said Bartley, who is currently analyzing biosamples from Swedo’s 2016 clinical trial that tested intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) as a treatment for PANDAS.

“We’re really antibody hunting because the autoantibody [for PANDAS] hasn’t been identified yet,” he said. “We are using these platforms that allow us to determine the identity of the antibody targets, and then we can ask definitively if they only occur in PANDAS or if they occur more broadly. Secondarily, do they react with group A strep or other microbes?”

Bartley added that a diagnosis of PANDAS, for now, often is mischaracterized as seronegative autoimmune encephalitis (PMID: 37210100); it is not in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, which can complicate health insurance reimbursement.

In a separate hunting expedition, Bartley found autoantibodies in two teenage patients who had developed neuropsychiatric symptoms after COVID infection. That case report also validated a novel autoantibody against an intracellular protein implicated in a neurodevelopmental disorder and in schizophrenia (PMID: 34694339). And in an upcoming study using PhIP-Seq, Bartley and colleagues hope to demonstrate how some of the antibodies that bind to SARS-CoV-2 also bind to human proteins, consistent with the concept of molecular mimicry.

Bartley also developed a PhIP-Seq analytic method that his colleagues used to identify an autoantibody profile in some people that was predictive for multiple sclerosis (MS) and showed that some of those patients have axonal damage years before symptom onset (PMID: 38641750). This result extends an established consensus that Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is necessary but not sufficient for developing MS, and it suggests that some people’s immune systems may react—and cross-react—differently to EBV antigens compared with those who don’t develop MS.

Down syndrome regression disorder (DSRD), too, might have an autoimmune component, said Bartley, who is a co-investigator on a related NIH-funded Bench-to-Bedside study with GenaLynne Mooneyham (NIMH), Eliza Gordon-Lipkin (NHGRI), Jonathan Santoro (Children’s Hospital Los Angeles), and Aaron Besterman (Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego). In DSRD, children with DS lose functional status at a young age, and those patients seem to respond to immunotherapy, according to Bartley. “We have an active research program looking for autoantibodies in those individuals and are admitting patients to the Clinical Center for phenotyping.”

Post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome

CREDIT: NIAID

Lyme disease is caused by the Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria, show here in red. Even after treatment with antibiotics, some people develop a constellation of nonspecific symptoms known as post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome.

Another compelling mystery is the long-term effects of Lyme disease, the leading vector-borne disease in the United States, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria and carried by ticks. Most people who get Lyme disease will recover with antibiotic therapy, but a portion of patients will complain of fatigue, muscle and joint pain, sleep problems, and brain fog. This syndrome of nonspecific symptoms is called post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome (PTLDS). In 2023, NIH awarded five projects to fund research aimed at better understanding the syndrome.

CREDIT: CHIA-CHI “CHARLIE” CHANG

Adriana Marques

“Possible drivers of symptoms after Lyme disease [include] immune dysregulation, autoimmunity, antigen persistence or ongoing infection, preexisting and new conditions, and psychosocial influences. Our current work addresses all these areas,” said Adriana Marques, chief of the Lyme Disease Studies Unit at NIAID’s Laboratory of Clinical Immunology and Microbiology.

Marques' team is working on a clinical study that evaluates and follows patients with PTLDS. They are exploring different methods and markers to assess the cause of symptoms, which can help in the development of new treatment studies.

CREDIT: RONJA FRIGARD, NIAID

At NIAID’s Lyme Disease Studies Unit (LDSU), scientists are researching possible causes behind the symptoms of post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome. LDSU postbaccalaureate fellows Emma Tilley and Sohan Chacko are shown here examining Ixodes scapularis larval ticks, a Lyme disease vector.

For example, they collaborate with investigators at Tufts University (Boston) to study antiphospholipid antibodies produced in response to B. burgdorferi infection (PMID: 35289310). The early data suggest that these antibodies showed up earlier after infection and were cleared more quickly, and more research is needed to determine whether these antibodies will help in early diagnosis of Lyme disease, in diagnosis of reinfection, or to track the response to therapy. Marques is also working with collaborators at Columbia University (New York), studying the antibody response at different stages of Lyme disease and PTLDS.

Long COVID and viral remains

Long COVID has been dominating the news. One theory on how long COVID perpetuates is that bits and pieces of the COVID virus—shards of RNA and proteins—remain in the body and continue to fuel a slow-burning immune response, contributing to inflammation and resulting in symptoms such as cognitive difficulties and fatigue.

CREDIT: NINDS

Brian Walitt

“Are there differences in the types or amounts of viral remnants in long COVID participants compared to healthy volunteers?” asked Brian Walitt, a staff clinician in the Interoceptive Disorders Unit at NINDS and part of a multidisciplinary team running an ongoing long COVID clinical trial at the NIH Clinical Center. “Data suggest there’s residual material in people, but it’s not clear how different it is in recovered versus not recovered individuals. Is there a difference in the host responsiveness to those remnants, and how do the viral remnants interact with the immune system?”

To answer these questions, Walitt and Avindra Nath, NINDS clinical director and senior investigator at the Section of Infections of the Nervous System, are launching a new study to analyze biopsies from tissue all over the body in living individuals. They intend to compare healthy participants after recovering from COVID with individuals with long COVID and look for remnants of SARS-CoV-2 RNA or proteins.

Data from the long COVID protocol have shown a dysregulation of antibody-producing B cells and infection-fighting T cells in some participants, and the investigators hope to determine whether some of that immune dysregulation might be due to the inability of some people to clear viral material.

Characterizing chronic fatigue

A condition that eerily shares some of the same symptoms experienced by those with long COVID, such as fatigue and cognitive difficulties, is myalgic encephalomyelitis-chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). A large multidisciplinary team at NIH was the first to link specific abnormalities or imbalances in the brain to the clinical symptoms of post-infectious ME/CFS. And the hunt is on for a cause.

CREDIT: PATRICK BEDARD, NINDS

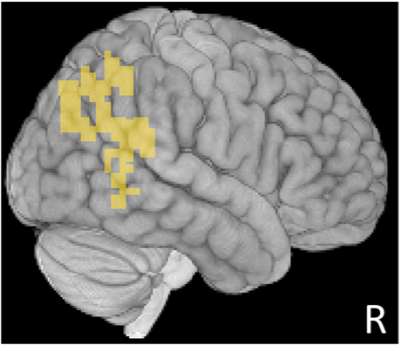

NIH researchers found persistent immune dysfunction in people with post-infectious ME/CFS, which the scientists hypothesize may have downstream effects by altering metabolites that affect brain function. Shown is a composite of functional magnetic-resonance images taken during a grip-strength test. The highlighted brain areas (bilateral temporoparietal junction, superior parietal lobule, right temporal gyrus) have decreased activity in patients with ME/CFS compared with those without the syndrome. Caption courtesy of NINDS.

Of note, the researchers used the same study design, common data elements, and comprehensive testing procedures as in the long COVID trial and found some overlap in the findings, including immune dysregulation. As with long COVID, the findings suggest that something in the periphery might be interfering with the immune system’s taking full action.

"We looked at a subpopulation with ME/CFS that was triggered by an infection, mostly respiratory or [gastrointestinal] infections, and those patients likely have an immune system that is exhausted and unable to clear the antigen. The immune cells look very different in these individuals compared to those that clear the infection,” said Nath, who was senior author on the study published earlier this year in Nature Communications (PMID: 38383456).

Immune-targeted therapies

Nath and Walitt now hope to launch a clinical trial to identify patients with long COVID and T-cell exhaustion and treat them with a PD-1 inhibitor, a checkpoint inhibitor drug sometimes used to treat cancer. According to Walitt, they hope to find out whether the treatment might help restore immune function and clear the viral material, perhaps having downstream effects on the central nervous system and other symptoms.

“It's the intervention most open to scientifically testing the clinical impact of the observed immune exhaustion that we have right now,” he said.

Another trial underway is treating long COVID patients with IVIG, a nonspecific immunotherapy that delivers a concentrate of antibodies. “Some people have a dramatic response, and some people don’t,” said Walitt. “The idea is to understand who the responders are and who are not so that we can predict response and know who to give it to.”

CREDIT: NINDS

Avindra Nath

Aligning the research agenda

In 2023, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine hosted a workshop titled “Toward a Common Research Agenda in Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses.” The event was attended by several members of NIH leadership and focused on aligning research toward uncovering biological similarities between diseases that could perhaps lead to treatments that might work across multiple conditions.

According to Nath, the present time is a golden opportunity to study these diseases. “We’ve made certain breakthroughs, but there is a lot that remains unknown about a whole host of diseases that look very similar phenotypically but have different names,” he said. “If you find a treatment for one of them, then you might just find a treatment for all of them. There’s room for specialists to really study them, apply their expertise, and make a real difference.”

Interested in learning more about infection-associated illnesses?

The 7th Annual Children’s National Hospital-NIAID Symposium is on September 5, 2024. This one-day, in-person event will be held at Children’s National Research and Innovation Campus in Washington, D.C. This year’s theme will be “A New Paradigm: Infection-Associated Chronic Illnesses Affecting Children.” Registration is free, and up to 8 hours of CME credits will be available to attendees. More information is available at the event website.

Furthermore, hear a panel of experts discuss their research on the potential viral triggers of autoimmune disease at a science talk on NIH VideoCast, hosted by the Office of Autoimmune Disease Research, housed in NIH's Office of Research on Women's Health (OADR-ORWH). OADR-ORWH hosts a series of science talks to examine the state of the science in specific areas impacting autoimmune disease research and research in women’s health.

This page was last updated on Thursday, December 5, 2024