Clear Plastic Aligners Give Patients with Brittle Teeth New Smiles

Multicenter Clinical Trial Aims to Improve Oral Health for Those With a Rare Disorder

BY TIFFANY CHEN, NIDCR

Although 18-year-old MinFen Lydia Foreman loves food—everything from dumplings and pho to fried chicken—she has to be extra careful with each bite. “Sometimes little pieces of teeth can break off,” said Foreman. “I can’t really eat hard foods.” Snacks like nuts, hard candies, and bowls of popcorn with half-popped kernels are off her menu.

Foreman was born with osteogenesis imperfecta (OI), a rare genetic disorder commonly known as brittle bone disease. It affects fewer than 20,000 people worldwide. Because OI disrupts collagen production, which is crucial for building strong bones and teeth, Foreman is smaller than most teenagers, and her bones break easily. The condition not only undermines bone strength, but it can alter skull development and cause dentinogenesis imperfecta, a disorder marked by fragile and discolored teeth.

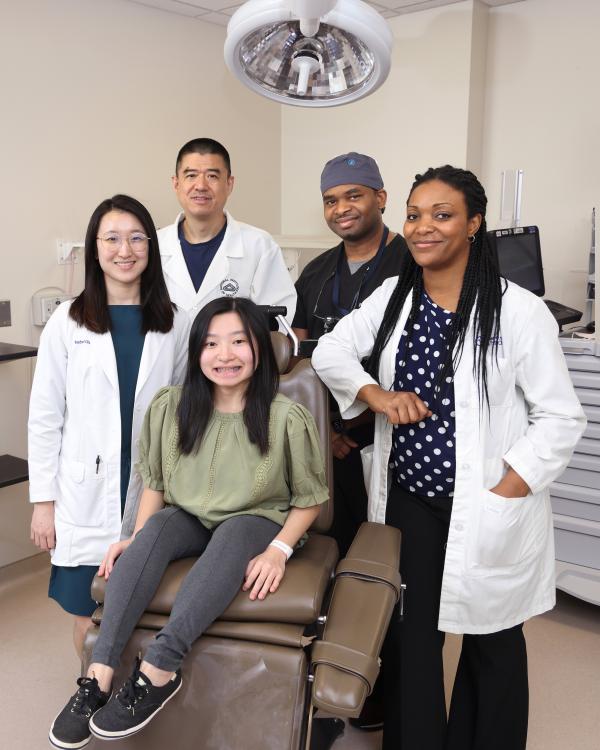

CREDIT: NIDCR

Clinical trial participant MinFen Foreman (seated) posed with members of NIDCR’s clinical team (from left to right), physician assistant Rachel Chung, doctors Ling Ye and Ayodeji Awopegba, and research nurse Danielle Elangue, at a recent visit.

“Because of OI, these patients have an unusual teeth misalignment called posterior open bite, which means that their back teeth are not touching, while their front teeth are,” said Janice Lee, NIH’s deputy director for intramural clinical research and clinical director at NIDCR. “As you can imagine, this really limits their chewing capacity, and they may be swallowing food whole. It really is a quality-of-life issue for these individuals.”

For the past year, Foreman has been part of an international multicenter clinical trial funded by NIH that is testing the effectiveness of FDA-approved clear plastic aligners to improve dental function in patients with OI. Lee leads the trial’s NIH site.

Orthodontists usually treat misalignment of healthy teeth with braces and sometimes surgery in more severe cases. However, neither treatment is optimal for patients with OI, whose misalignments are complex and whose teeth are fragile. “I had a patient with OI who chipped her upper front tooth eating a burrito,” said Ling Ye, a volunteer orthodontist involved in the clinical trial. “Their teeth may appear normal, but they have weak structure. Conventional braces may not be a good option.”

Surgeries to realign teeth by cutting the jawbones are also not an option. In part, this is because clinicians and researchers are unsure how the facial bones heal in patients with OI.

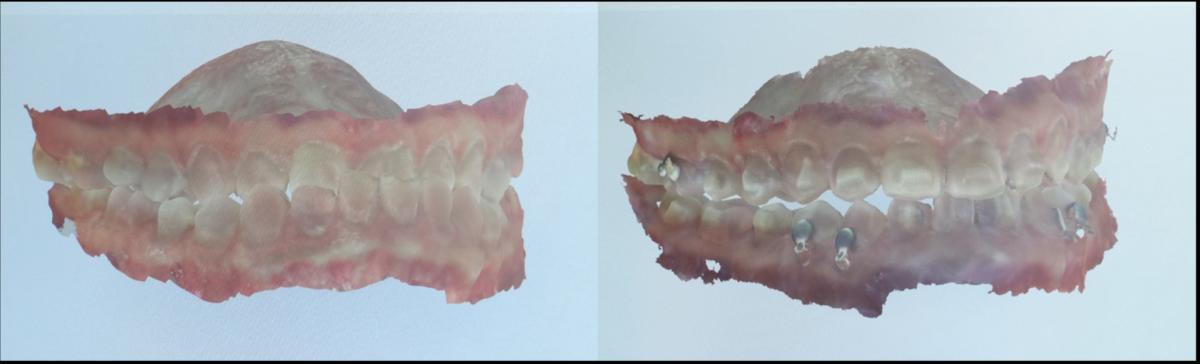

CREDIT: NIDCR

The clinical trial tests whether clear aligners can correct teeth misalignments in patients with brittle teeth due to osteogenesis imperfecta.

“It was clear that there is an enormous unmet need in the patient community, and there have been no clinical trials tackling this problem,” said Brendan Lee, a pediatrician and geneticist at Baylor College of Medicine (Houston), who oversees the multicenter trial. “Seeing how clear aligners are now in widespread use and relatively safe, our team wanted to test whether they could be a potential solution.”

Twenty eight participants are currently enrolled in the clinical trial. Clinicians take 3D oral scans to customize the aligners to each patient’s teeth and develop a two-year treatment plan. Over time, the clear aligners gently and evenly distribute pressure across the teeth to gradually reposition them. Patients usually wear a set of aligners for a week or two before moving on to the next set.

CREDIT: NIDCR

The researchers evaluate Foreman’s chewing ability with a color-changing gum that turns pinker the more chewing improves.

To evaluate dental function, the researchers follow up with patients in the clinic every two months. They assess treatment progress by comparing 3D oral scans over time and measuring chewing ability with a color-changing gum, which shifts from green to pink. The better a person chews, the pinker the gum becomes.

So far, the trial’s clear aligners have shown promise as a gentler yet effective treatment for patients with OI. Patients have responded well to the treatment and have experienced few side effects. Foreman’s 3D scans show that the clear aligner is moving her teeth and improving her posterior open bite and underbite. According to the gum test, her chewing ability has improved.

“I have already noticed how different she feels about herself, her smile, and her teeth,” said Dee Foreman, MinFen’s mother. “It’s about chewing, eating, and swallowing, but the changes in her face have also given her confidence in such a positive way.”

CREDIT: NIDCR

Clinicians take 3D oral scans to track patients’ progress. Scans of Foreman’s teeth after one year of clear aligner therapy show improvement in her posterior open bite and underbite.

Janice Lee, who is also an oral maxillofacial surgeon, noted that the therapy’s aim is not one hundred percent perfection but is intended to offer an alternative to major surgeries that can be risky for patients. The team hopes the results can help guide orthodontic treatment for patients with OI and allow dental practitioners to feel confident in offering the therapy one day to patients. Beyond benefiting the OI community, the clinical trial’s results could further establish the safety of clear aligners and inform standards of care for the general population.

“Before the clear aligners, chewing meat was tough,” said Foreman. “I had to chew for a long time, and it would get stuck in my teeth. Now, I can chew more easily, and I am excited to see my bite fixed and have a pretty smile.”

The clinical trial is actively recruiting participants with OI aged between 12 and 40 years. Visit the trial website for details.

Tiffany Chen is a science writer at NIDCR. When not turning scientific discoveries into engaging stories, she’s either on the couch binge-watching a new show or off on a spontaneous adventure somewhere in the world.

This page was last updated on Thursday, December 5, 2024