The Jugglers

Balancing a Scientific Career with Raising a Family

ILLUSTRATION BY CHRIS RYAN, NATURE

Reprinted with permission from Springer Nature: Chris Ryan, Nature 2015 (From Powell, K., “Work–Life balance: Lab life with kids,” Nature 517:401–403, 2015).

“It’s hard to feel good at everything,” senior investigator Deborah Citrin (NCI) concluded after talking about the inherent and unavoidable “work–life imbalance” of being a PI and a mother of three. Her husband, a surgical oncologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland), has been deployed five times. So she has the challenge of single-handedly holding down the home front while working at NIH and running a laboratory and clinical trials. And yet she and her husband have managed to successfully juggle their careers with family-raising responsibilities.

“Remember, everybody is struggling,” she warns. Be wary of the “glossy image” of the working parent who seems to be excelling in all aspects of his or her life. (See Citrin’s and others’ stories below.)

Everyone deals differently with how to balance raising a family with moving forward in a career, but such jugglers share common problems and use similar techniques in juggling the demands of family and research.

For this issue of the NIH Catalyst, we interviewed NIH scientists of all types, at all levels of their careers, and at all stages of raising their families—from having infants to having grown children. We did a similar story in 1996 (November-December 1996 issue of the NIH Catalyst).

The parents we interviewed appreciate all the resources NIH has to offer; the support, understanding, and sensitivity of their supervisors; and, in many cases, the ability to have flexible schedules and even being able to work from home at crucial times. The parenting resources include child-care centers; lactation rooms for breastfeeding mothers who need to pump milk at work; a LISTSERV; webinars and seminars; parenting coaches; and resource and referral services. (See the “Parenting Resources” article in this issue.)

In addition, the Intramural Research Program’s (IRP) “Keep the Thread Program” offers postdoctoral fellows several options for increasing flexibility and temporarily reducing effort while remaining connected to their research and the NIH community during times of intense family needs. In 2008, the IRP extended the tenure clock (normally six years; eight years for anyone doing clinical or epidemiological research) to seven years (nine for clinical or epidemiological research) to allow a candidate extended family or sick leave, using leave and/or leave without pay for reasons such as childbirth, adoption, major illness, or family emergency.

Still, the NIH scientist–parents had suggestions for what else NIH might do—such as expanding the child-care program—as well as advice for other parents—ranging from not being afraid to ask for help to learning to be more efficient at work and at home.

But all agree that any trade-offs are worth it. Kids add so much fun to life, said senior investigator Judith Walters (NINDS), whose children are grown. A parent’s love for their children is “an uncomplicated type of love” that makes all the lifestyle adjustments worth it.

Following are the full interviews.

The Stadtman Couple

Astrid Haase, M.D., Ph.D., Earl Stadtman Tenure Track Investigator, Acting Section Chief, RNA Biology Section, Laboratory of Cell and Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

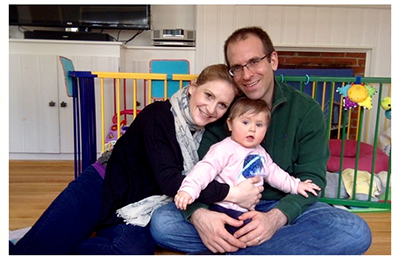

Markus Hafner, Ph.D., Earl Stadtman Tenure Track Investigator, RNA Molecular Biology Group, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

Child: Julia (one year old)

Astrid, Julia, and Markus

Two postdocs from rival labs meet at a conference, fall in love, get married, and have a beautiful daughter. It sounds like a science fairy tale, but for Astrid Haase and Markus Hafner, it’s just their story. Add some success with both being hired at NIH as tenure-track Stadtman Investigators, and you have a power couple pushing science and co-parenting to the limit.

Even when ramping up their labs, they knew they also wanted to be parents. So, with the arrival of daughter Julia last year, they’ve found ways to be more efficient. The occasional afternoon coffee with leisurely scientific discussions have given way to more regimented and exact schedules, with the goal of finishing the day at a reasonable hour to allow for family time. However, both Astrid and Markus agree that they haven’t shifted too much of their work–life balance—they just spend less time on extracurricular activities.

Although tenure-track clocks can be extended for up to a year for life events (such as having a baby), both Astrid and Markus hope that they won’t need the additional time. (The typical time for a tenure-track investigator to achieve tenure is about six years. Markus started in 2014, and Astrid in 2015.) They attribute their sustained productivity to their cooperative teamwork style of parenting. Parental leave for them was more like working from home, with each parent taking turns being responsible for Julia while the other e-mailed the senior postdocs who ran each lab in their absence. Markus also had to have several ankle surgeries to repair a chronic problem and was unable to walk unassisted for the first few months of his daughter’s life. Both Astrid and Markus felt that their scientific directors were extremely supportive, which made both life events easier to weather.

One complaint most NIH parents have is the ever-present problem of finding child care. The couple got on the wait list for NIH child care when Astrid was in her first trimester of pregnancy. They are in the upper third of the list now but worry that when Julia ages out of her current child-care center at age 2 there may not yet be a spot for her at NIH. They are frustrated by the lack of transparency regarding the wait list.

Both Astrid and Markus felt that having children later in their career was beneficial because their home budget isn’t quite as tight now as it was during their postdoctoral training. They also have a greater flexibility in running the lab remotely now.

Astrid was inspired by one of her postdoctoral advisors at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (Cold Spring Harbor, New York) who had a baby by herself later in life and didn’t let anybody question her decisions. “Don’t compromise,” Astrid said. “If you want to have kids then have them, but it’s key to find the right partner.” She was grateful that Markus never questioned her desire to have a career and a family.

Julia has some big shoes to fill. As two successful scientists, Astrid and Markus agree that their daughter should do “whatever makes her happy, but with an expectation of some college.” What if she wants to be an astronaut, Markus wondered. Astrid quipped that, in that case, she’d hide in Julia’s suitcase and accompany her to outer space.

Use Your Village

Patience Green, M.D., Clinical Fellow, Endocrine Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute

Spouse: None

Children: Two: son, Perry (13 years old); guardian for sister, Stephanie (15 years old)

Perry, Patience, and Stephanie

“Being a single parent, you’re dishwasher, chef, you clean, [and] you have to always be physically and emotionally present,” said Patience Green, who has a 13-year-old son and is the guardian for her 15-year-old sister. “You have to adjust everything and make the most of opportunities when you have them.”

She had her son when she was an undergrad in college—at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Although she had a scholarship, she took out loans to cover child care. She had a great support system, too: Her girlfriends and classmates loved babysitting Perry. And her mom provided emotional support, encouraging her to pursue her dreams.

“My mother was determined that I would finish college and go on to make a life for myself and my son,” said Patience. Having a child “forces you to grow up very quickly—there’s no time to party,” she said. “You have someone else depending on you.”

She took two years off before medical school—her son was in pre-kindergarten by then—to work in a salaried job that allowed her to afford after-school care. She returned to her hometown of Atlanta to attend Morehouse School of Medicine and to be near family who could help with six-year-old Perry. She and her son lived in an apartment for the first three years of medical school and then moved in with her parents during her fourth year.

In 2014, she started her surgical residency training at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C. “Residency was very draining,” she said. “You’re responsible for the wellbeing of other people.” It was heartbreaking to deal with the death of a patient, treat a young person with cancer, and work with others who were very ill. But she tried not to bring the heartbreak home, which didn’t always give her enough time to emotionally process what she was dealing with at work.

During Patience’s second year of residency, she offered to let her 12-year-old sister come live with her so she could attend school in Washington, D.C. “Life was a bit more of a juggling act when my sister moved in with me,” said Patience. “I had to find time for extracurricular activities, school projects, and doctor’s appointments for two children instead of just one.” But she loved having both children, and it was especially nice that Stephanie and Perry were like brother and sister. “It allowed me a bit more time to myself.” Now that the kids are older, “they can cook, clean, [and] get themselves on the bus.”

Even with the kids being more independent, “it’s challenging raising a family,” Patience said. “You have to be available if an emergency arises at work. Finding the balance is hard. You feel the pressure to take care of the patients and feel awkward if you have to get someone to cover for you.”

Right now, she’s finishing a two-year fellowship at NIH—the first year involved caring for patients, and the second year is devoted to research, giving her more flexibility in her hours. She’ll return to Howard to complete her surgical residency in July 2018.

At NIH, she’s taken full advantage of several resources: Mom-Dad-Docs; Single Parents Support Group; Resource and Referral Services (to find a summer camp); and the Lunch and Learn Seminars. Her advice to other parents: Join a support group; plan mommy dates with other moms; plan play dates if you can squeeze them in; and take care of yourself. She admits she hasn’t always done a good job with self-care, but now she plays videogames—some with the kids and some on her own—to relax and unwind.

She has advice for senior scientists, too: Be supportive of the people you supervise; if you have kids, make yourself available for Mom-Dad-Docs; and “Don’t make people feel bad about things they can’t control.”

But her biggest piece of advice to parents is “Use your village.” Reach out to other people—you never know who’s willing to help.

Be Sure to Have Balance

Michele K. Evans, M.D.: Senior Investigator, Laboratory of Epidemiology and Population Science, National Aging Institute (NIA); Deputy Scientific Director, NIA

Charles Egwuagu, Ph.D.: Senior Investigator and Chief, Molecular Immunology Section, Laboratory of Immunology, National Eye Institute

Children: 2 daughters: Jemeh (37 years old); Emeka (22 years old)

Clockwise from top left: Emeka, Jemeh, Michele, and Charles

“Don’t make work your whole life,” Dan Longo told Michele Evans shortly after she married Charles Egwuagu, who was the single parent of a 12-year-old daughter, Jemeh. “You need to be sure you have balance.” Longo, Evans’s scientific director in the National Institute of Aging (NIA), also pointed out that she would need to make her stepdaughter feel she was important.

Both Michele and Charles have succeeded in raising Jemeh and a daughter they had together, Emeka, while working full-time at NIH. But the way wasn’t always easy. Charles became a single parent when he was in graduate school at Yale and Jemeh was three years old. Although she was in a co-op child-care program run by the parents, Charles would sometimes bring her to the lab when he needed to work and child care wasn’t available. (The other members of the lab loved having her around, though.) And being a male single parent of a daughter made other parents in Jemeh’s Girl Scout Troop and other social settings uneasy. But he soon gained their trust and was even made cookie chairman for his daughter’s troup.

Charles came to NIH in 1987 as a staff fellow in the National Eye Institute when Jemeh was six years old. She sometimes came to NIH after school and once her homework was done, her “job” being to organize pipette tips and other lab supplies. Charles’s lab chief, Robert Nussenblatt, and other colleagues were very supportive and didn’t mind when he had to leave early for teacher meetings, doctor appointments, or other child-related activities.

Michele came to NIH as a clinical associate in the National Cancer Institute (NCI), in 1986, after completing an internal medicine residency at Emory University Affiliated Hospitals in Atlanta. She became a senior clinical investigator at NCI in 1990 and moved to the NIA (located in Baltimore) in 1992.

Charles and Michele met in 1992 when they were members of NIH’s Committee on the Status of Intramural Minority Scientists and married in 1995. “Jemeh [now] had a woman to talk to,” about female issues, said Charles. And when she learned that Michele was a speech and debate coach and had won trophies for debating, Jemeh wanted her advice for getting into the debate club.

Emeka was born in 1996, nine weeks early, and had to spend her first couple of weeks in the neonatal intensive-care unit before being sent home.

Luckily, Michele and Charles were able to hire a nanny (the waiting list for NIH child care was too long) when Michele went back to work. And Charles’s mother, who lived in Nigeria, came to spend three years with the family. She helped oversee the nanny and baby; paid special attention to teenage Jemeh (even making sure that homework got done); and gave Charles and Michele the chance to have time with each other as well as private time with Jemeh.

Michele breastfed Emeka for 15 months, which meant having to pump breast milk at work to take home. Although lactation rooms weren’t common at NIH in the 1990s, Longo made sure that NIA got one and made it available to all new mothers.

Even with child-care help at home, balancing home life with work goals can still be challenging, especially for women. “I was able to raise my kids and get tenure with a lot of prayers and hard work,” said Michele. But it took her about twice as long to achieve tenure as it did her husband because she was the one who mostly took time off from work to deal with doctor appointments and other family matters.

Charles, who served on the Central Tenure Committee for four years, observed that many female scientists chose being staff scientists or staff clinicians over being on the tenure track so they could have more flexibility in their work schedules. He wishes that there were a way for women to more easily transition to the tenure track later on. He also wishes that NIH would fix the child-care shortage problem.

Michele wishes that senior scientists gave more thought to mentoring their postdocs and making a commitment to their ultimate success. “Life intrudes,” so it’s important to negotiate how to work with them when things change, she said.

Both Michele and Charles are grateful for the support they got from their supervisors and colleagues along the way. “The key is the culture of the place,” said Charles. At NEI’s Laboratory of Immunology, “It’s like a family and it made a difference.”

“You have to live your life,” Michele said. “The most important thing is living the [non-work] part of your life—finding a spouse, having children, and making [family] a priority.”

Jemeh graduated from the College of William and Mary (Williamsburg, Virginia), got an M.P.H. from Johns Hopkins (Baltimore), and is working in Abuja, Nigeria, with a United States Agency for International Development program to prevent and treat mother-to-child transmission of HIV-AIDS. Emeka is graduating this May from the College of William and Mary and is headed to Columbia Law School (New York) in the fall.

“Nothing is more fulfilling than seeing your kids get out on their own and pursue their own life goals,” said Michele. Charles smiled and nodded in agreement.

How Much You Love Your Kids

Andrew Kehr, Ph.D.: Postdoctoral fellow, Laboratory of Cellular and Molecular Biology, Structural Cell Biology Section, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Jaqueline Kehr, M.S.: Management Analyst (contractor), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Children: One daughter, Elna (16 months)

Jacqueline, Elna (age 1), and Andrew

Balancing a career and raising a family can be difficult for any couple, but Andy and Jackie Kehr—who met as undergraduates at DePauw University (Greencastle, Indiana), got married in 2012 while Andy was in grad school, and waited until they got to NIH to start a family—faced extraordinary challenges when their daughter Elna was born. She aspirated meconium (a baby’s first stool) at birth and suffered severe respiratory problems that sent her to the hospital three times. Luckily for both Andy and Jackie, their bosses, who are strong women scientists with children of their own, have been supportive and allowed the couple to modify their work schedules so they could attend to their daughter’s needs. Jackie even teleworked from the hospital and when Elna returned home, Andy switched his hours so he could help out during the day.

Elna, at 15 months, is in child care in Bethesda now. Although postdoc schedules can be erratic and the hours long, Andy makes it a point to get home early every night so he can help with dinner, bath time, and reading stories to Elna. Then, around 8:00 p.m., he’s back to work—usually on the computer at home, writing papers and doing other work related to his research.

Andy and Jackie are both grateful not only for their supportive bosses and colleagues, but also for the resources NIH offers: the health insurance provided by the Foundation for Advanced Education in the Sciences (FAES); the Nursing Mothers Program; “Mom-Dad-Docs” webinars, especially one about getting your kids to sleep; and NIH’s “Resource and Referral Services” to find accredited child-care programs. They are also on the NIH Parenting LISTSERV, where they’ve learned about free items and coupons other parents are giving away, gotten advice on finding a pediatric dentist, and even learned what to do if the power goes out and makes their daughter’s nebulizer inoperable. A pediatrician parent on the LISTSERV suggested getting an albuterol rescue inhaler with a spacer as a backup.

The couple was surprised and disappointed to learn, however, that they are not eligible for the “NIH Child Care Subsidy Program” (only NIH G.S. and Title 42 federal employees can take advantage of that) or for child- and dependent-care federal tax credits (because Andy is not salaried and, as a postdoc, is working off a grant).

The Kehrs hope to be able to enroll Elna in one of NIH’s child-care centers—they’ve been on the waiting list since Jackie knew she was pregnant, but don’t know how much longer the wait will be.

They’ve have been fortunate to have help from family and friends. Their parents, who live in Indiana, have come to stay a few weeks at a time to help out. And long-time friends have pitched in, too.

Making new friends has been hard, though. “It’s the first time we’ve entered a place not as a cohort,” said Andy. In college and graduate school, people start together as a class and you make friends among your classmates. And although the Kehrs have made friends with other parents who attended the same birthing classes, those people have moved away.

Still the couple does have fun. They take their daughter—in a baby carrier—on hikes. Both are learning to home brew beer and like to bike to work together in nice weather. Andy enjoys tinkering with a tiny Raspberry Pi computer and teaching a course at FAES. And Jackie loves gardening.

The Kehrs aren’t sure what’s next when Andy finishes his postdoc in two and a half years. He’d like to stay in academia and possibly teach at a liberal arts university. Jackie may pursue her Ph.D. once she sees where they settle next. And both will continue to do their best managing their careers and raising a family.

What surprised them the most was how unprepared they were for “just how much you love your kids,” said Andy. “I don’t sleep [or] hang out with friends. But when [Elna] giggles…it doesn’t matter.”

Energetically and Efficiently

Amy Newman, Ph.D., Senior Investigator, Molecular Targets and Medications Discovery Branch, Medicinal Chemistry Section, National Institute on Drug Abuse

Nigel Greig, Ph.D., Senior Investigator, Translational Gerontology Branch, National Institute on Aging

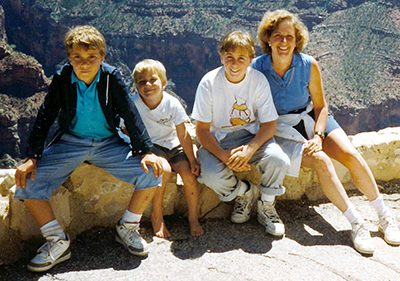

Children: Three: daughter Kelly (27), son Josh (26), daughter Katelyn (24)

Amy and Nigel’s family in 2000. Clockwise from top left: Amy, Nigel, Josh (8), Katelyn (6), and Kelly (10).

Amy Newman and Nigel Greig are both established principal investigators working at NIH’s Baltimore campus. They seemed to have made science and parenting fit together seamlessly. Having three kids while Amy was on the tenure track in the 1990s surely was full of challenges, but Amy and Nigel approached running their family the same way they run their labs—energetically and efficiently.

Mastering time management is key. For example, Amy uses the same “highs-and-lows” discussion in lab meetings as she did at Sunday dinners with the family: Everybody gets a chance to describe one positive “high” event and one negative “low” for the week; others chime in with suggestions, words of support for the lows, and celebrations for the highs. And Nigel sees that the ability to constantly problem solve and strategize is just as helpful at home as it is in the lab.

Amy and Nigel remember the early years with their family fondly and count their blessings for all the help they received. They had a dedicated, reliable nanny for almost five years, negating the sick-day dilemmas with which most parents struggle. Amy’s parents also moved in during the summers to provide child care. Even with this help, Amy always tried to provide her kids with all the opportunities she could “as if she [weren’t] working”–which sometimes meant leaving the lab early to chaperone a field trip and letting Nigel take the children to meetings (in nice places), even if she couldn’t attend. Finally, their commitment to their family involved a semi-mandatory “meet around the dinner table” every night. No matter how late anyone returned home from work, school, or extracurricular activities, dinner was a shared family experience.

Although some view being a scientist as a family-unfriendly option, Amy and Nigel praise the flexibility of science—being able to set your own schedule and work remotely, and to use the ability to adapt to unforeseen circumstances that being a scientist requires. These factors can make science and family an excellent fit.

“You have to have openness, much like science, to see the big picture, to see the direction you’re going, [and] to not get delayed by the small stuff that can ruin it,” said Nigel. “You just have to keep things fluid and positive.”

For the junior scientists in their labs, Amy and Nigel have tried to model what a great balance looks like. They try to be flexible with trainees who have children and remind people that working at the NIH provides rich opportunities, of which they hope trainees can take advantage even while adjusting to a new family dynamic. Achieving a balance requires innovation and a great work ethic, but ultimately happy postdocs are more productive.

Each year, Amy and Nigel invite lab members, past and present trainees, collaborators, and their families to an all-day summer pool party at their home. Socializing with other scientists is fun and often yields unexpected outcomes including finding collaborators for projects.

In addition to sharing responsibilities as a parenting team, Amy and Nigel share scientific ideas and experiences and provide professional support to one another. They also credit their shared fundamental value system and marriage compatibility as some of the biggest components of success in the lab and with their family.

Their children today? Kelly is a strategist for Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and is pursuing an M.B.A. at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles); Josh is at Georgetown University School of Medicine (Washington. D.C.) and will start a residency in neurology at Washington University in St. Louis (St. Louis, Missouri) in June; and Katelyn is a journalist at U.S. News & World Report, focusing on environmental and health science.

Take the Free Stuff

Kate Brown, Ph.D., Visiting Postdoctoral Fellow, Thoracic and Gastrointestinal Oncology Branch, National Cancer Institute

Spouse: Alex, an event organizer

Children: son (Orson, 5 months old)

Kate and Alex and their son, Orson

One of the things Kate Brown, a visiting fellow from England, feared most about childbirth was walking out of the hospital with a huge hospital bill. The British health-care system is free, but Kate had heard horror stories about the health-insurance system in the United States and expected the worst. She was relieved, however, to discovered that her FAES-sponsored health insurance covered everything except doctor copays and a $250/person copay for overnight hospital stays.

She was diagnosed 34 weeks into the pregnancy with preeclampsia—a potentially life-threatening pregnancy complication that causes high blood pressure, kidney damage, and other problems—and put on modified bed rest for three weeks. Luckily, her P.I. allowed her to work from home so she was able to keep up with her responsibilities. At 37 weeks, Orson was born by caesarean section, and mother and baby stayed at the hospital for four days. Kate and her husband were grateful for that health insurance.

Kate also feels fortunate that postdocs have eight weeks paid leave so she was able to stay home, recover from her caesarean, and enjoy lots of time with her new baby. And when she returned to work, her husband was a stay-at-home dad and worked part-time from home. Orson recently started in a child-care program in Bethesda.

Finding child care was an unexpected struggle for Kate and her husband, who is from England, too. In England, most moms get a paid year off (dads usually get some paternity leave, too) after having a child, so finding child care right away isn’t a concern. “We should have put ourselves on the waiting list before we were pregnant,” she said. “NIH day care is good and convenient, but unrealistic given the current wait-list situation,” Kate said. “They should be transparent about how long it can take for a place to become available.”

Kate has discovered NIH’s other parenting resources such as the “amazing” NIH Parenting LISTSERV (she’s gotten some secondhand clothes and toys); the Nursing Mothers Program; and others she plans to use soon.

Still, even with an understanding supervisor and many resources, balancing work and family is not easy. “There’s not enough time in the day to get everything done,” she said. She makes the calls about finding child care and scheduling doctors’ appointments and does as she can much online in the evenings. “I’m the organizer in the family [and] it’s been hard to let go of that.”

She and her husband also get help from family—who live in England and come stay for an extended period—and friends. But it’s hard not having family nearby.

Kate’s advice to new parents: “Take as much free stuff as you can.” The hospital may offer diapers, diaper wipes, formula, and other items, such as pacifiers and rash creams that can’t be used again. And if your friends throw you a baby shower (“a very American thing”), register at stores for gifts because you’ll get welcome packets that include everything from coupons to different brands of baby bottles.

Kate always expected to come back to work, but was surprised at “how emotionally hard it was [to] leave Orson,” she said. “First thing I do when I get home is to pick him up.”

Live Your Life

Adam Messinger, Ph.D., Staff Scientist, Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, National Institute of Mental Health

Spouse: Kira, Advanced Practice Nurse

Children: Three children: Son, Micah (10 years old); daughter, Lylah (14 years old); son, Jonah (19 years old)

From left to right (back row): Adam, Lylah, Kira, Jonah; (front) Micah (San Diego, 2017)

Adam Messinger has had children during each stage of his career: his first son was born while he was in graduate school (University of California at San Diego), his daughter when he was a postdoc at NIMH, and his second son when he was just about to become a staff scientist.

Even with the experience of having children at such different stages of his career, he maintains that there is no good time to have children as a scientist. He pointed out that when you are a graduate student, your colleagues and PI generally expect you to be single and are thus less accommodating when you need to take time off for your children. As a postdoc, your having children is more typical, so there are more resources available. When you’re starting a new job, it can be difficult to juggle the responsibilities of also having a baby.

Adam’s wife, Kira, is an advanced practice nurse, and though her schedule is more rigid than his, they have found ways to balance the duties of parenting. Adam’s schedule allows him to take care of the children in the morning and walk them to school while Kira leaves early for work. She comes home earlier than he does to watch the children in the afternoon. Both of them were able to take some family leave when each of their children were born, and Adam is grateful that his PI was very supportive.

As for child care, neither Adam nor his wife had family nearby to help with taking care of the children, so they put their first into child care once he was about six weeks old and hired a nanny for their next two. Adam appreciated the NIH Child Care Center and had a good experience with it but wished that the postdoc discount had been higher and that efforts could be made to reduce the waitlist. He further notes that because postdocs make up such a large part of the NIH parent population, they should have more input into the governance of the Child Care Center.

He offers this advice: “You need to live your life…Do what makes sense for you [and] let the chips fall where they may. Science overall needs to realize that we [the scientists] are multidimensional creatures and always being in the lab is not the healthiest way to live.”

Unexpected Challenges

Lara Abramowitz, Ph.D., Postdoctoral Fellow, Laboratory of Cell and Molecular Biology, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Spouse: John, Engineer

Children: Son, Eli (2-and-a-half years old); daughter, Paige (7 months old)

Lara’s family (from left): Lara, Eli, John, and Paige

Lara Abramowitz had both of her children while working as a postdoctoral fellow but was quick to say that there is no ideal time to have kids while pursuing a career in science. Fortunately, fellows at the NIH can take up to eight weeks paid leave for the birth or adoption of a child. Lara also has a supportive PI and a positive and accommodating experience in her lab.

One of the most important considerations for Lara was knowing that she and her husband John—who is an engineer at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab (Laurel, Maryland)—could share child-raising responsibilities equally. Luckily, they both have flexible schedules, and John can sometimes work from home. Additional support from family members has been invaluable, too. Both her parents and her husband’s parents have been instrumental in watching the children—when they were infants before they entered child care, when one is sick, or when the child-care center is closed.

There are many unexpected challenges that arise when you have a baby such as how often children get sick. Lara said that if she took off time from work every time one of her children got sick, she’d never get anything done. The limited availability, years-long wait lists, and expense of child care was another unanticipated challenge. She encouraged people planning to become parents to set up child-care provisions even before pregnancy.

Lara found the Nursing Mothers Program and the lactation rooms to be very helpful. In addition, she welcomes advice from other scientists who have children. She is concerned, however, that not all parenting resources—such as the NIH child-care subsidy and NIH back-up care programs—are available to fellows.

Putting their passion for research on hold and leaving the work force is not a viable choice for many scientists. “You’ve invested so much into your career that you don’t want to leave,” Lara said. “Instead you find ways to have a great home and professional life, too.”

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask for Help

Xiaomin Yue, Ph.D., Research Fellow, Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, National Institute of Mental Health

Spouse: Rosemary, Senior Client Associate at a wealth-management firm

Children: 2 sons: Darius (6-and-a-half years old); Benjamin (8 years old)

Xiaomin’s family (from left): Rosemary, Benjamin, Darius, and Xiaomin

It can be difficult for scientist parents to gauge when they should have children. Much preparation goes into having a baby. Couples often wait until they are at the point in their career when they know resources will be available and they’ll be able to devote time to children. “Just as long as you’re ready, you’ll have the same experience,” regardless of what stage of your career you’re in, said Xiaomin Yue, who is optimistic about being able to balance raising a family with doing research. “Don’t wait!” Xiaomin, whose two sons are in elementary school, had his first during his postdoctoral training at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his second, soon after he came to NIH.

Both parents took some weeks off for parental leave when each of the children were born. Xiaomin’s parents came from China for about three years to help and were truly a key part of raising the children. Xiaomin and his wife, Rosemary, have been able to modify their work schedules to make it easier to share family responsibilities. Xiaomin takes the two boys to school in the morning and comes to work late. Rosemary, who had to request a modification of her work schedule six months in advance, starts and leaves work early so she can pick the kids up from school and be with them for the rest of the day.

Xiaomin was happy to find that the NIH parent community is so strong and that his PI has been so accommodating in allowing a flexible work schedule. As for NIH resources, Xiaomin found the parenting LISTSERV and the NIH Child Care Program to be the most helpful. While he acknowledged that the NIH child care was good, he suggested that it would be nice if NIH either had a summer camp program or offered a discount for summer camps elsewhere. Overall, he believes that NIH could use more feedback from parents—and keep them better informed—about resources, especially child care.

Xiaomin’s advice to parents: Take care of your children first and foremost (basing your research schedule on their schedules) and don’t be afraid to ask for as much help as possible.

Hard to Be Good at Everything

Deborah Citrin, M.D., Senior Investigator, Radiation Oncology Branch; Deputy Director, Center for Cancer Research National Cancer Institute

Spouse: Matthew, Army Surgical Oncologist

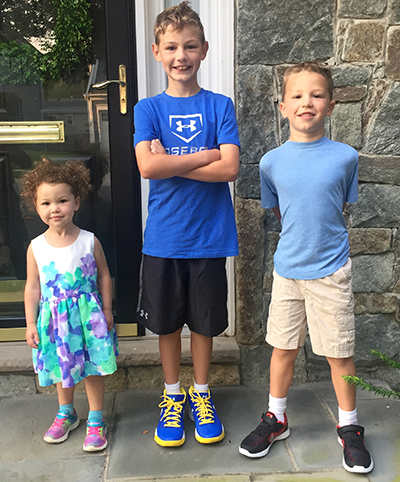

Children: 2 sons and a daughter: Ethan (10 years old); Benjamin (6 years old); Rachel (3 years old)

Deborah Citrin’s children (from left): Rachel, Ethan, and Benjamin (2017).

“It’s hard to feel good at everything,” senior investigator Deborah Citrin concluded after talking about the inherent and unavoidable “work–life imbalance” of being a PI and a mother of three. Her husband, Matthew, whom she met at Duke University School of Medicine (Durham, North Carolina) a week before classes started, works as a surgical oncologist at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center (Bethesda, Maryland). He has been deployed five times, for six to nine months at a time, giving Deborah the unique challenge of single-handedly holding down the home front while working at NIH and running a laboratory and clinical trials.

Deborah accomplishes this feat with child care for her little girl and before-and-after school care for her two boys. But even with extended child-care hours, Deborah has had to be out of the hospital more than she was accustomed to before she had children. She admits to “living at the hospital before kids,” but now her schedule is outlined by child-care hours. The upside is that Deborah has had to learn to be more efficient to meet the child-care center “deadlines” (when it closes). She stays on top of her work by being more task-focused at the hospital and more productive at home, using the evenings to review data and research papers once the kids are asleep.

Even so, unexpected interferences come up. A not-uncommon problem is when kids are sick or school is closed for snow days. Then Deborah must stay home or use the NIH’s “back-up care” babysitting resource available to federal employees. This service can provide last-minute child care a limited number of times a year. Deborah also feels thankful for supportive co-workers who cover the clinic if she needs to be out. “It takes a load off knowing you have people to help at a moment’s notice,” she said. “And we all try to return the favor.”

But there is no doubt that taking care of children is challenging. Deborah said that pregnancy was uncomfortable, and it took her a year to fully recover her efficiency. But the hardest part is after the child is born—everything takes longer, and there are many time-consuming tasks such as cleaning bottles and pumping breast milk. Deborah is grateful that she had a private office so she didn’t have to trek to a lactation room. She found the NIH lactation consultant very helpful. She expects other challenges down the road, such as paying for college.

Deborah offered the following advice to other parents who work outside the home: “Remember, everybody is struggling. We appear put together, but it’s not abnormal to feel stretched thin and like you are doing the best you can but, somehow, still feel inadequate.” Be wary of the “glossy image” of the working parent who seem to be excelling in all aspects of his or her life. There are some impossible expectations to overcome, such as being able to attend every interesting, faraway scientific meeting, which can be particularly hard for a PI who feels pressure to be visible in the field.

“It’s necessary to be okay with not doing it all.” But, she added, “Just hold on” because kids will grow up quickly enough and start to be more independent.

Having kids has been a great addition to her life, Deborah said. They provide a humbling perspective because they are not always impressed with what you do. For example, Deborah’s son asked her, “Why do you have a stethoscope? You’re just a radiation oncologist.” Deborah also recalls that several years ago when she was driving four-year-old Ethan to child care and they passed the playground outside the NIH Children’s Inn. He asked if that is where she and her NIH friends played all day.

Kids Force You to Be Involved

Jonathan J. Lyons, M.D., Assistant Clinical Investigator, Genetics and Pathogenesis of Allergy Section, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

Spouse: Christiana, proposal manager for a design-build construction firm

Children: son (Christopher, 2.5 years old); a daughter is due in June 2018

Jon’s family (from left) Christina, Christopher, and Jonathan

When asked what kind of sacrifices Jonathan Lyons has made for his family, he joked that he had to sell his BMW for a family–friendly Mazda. But, in all seriousness, he accepts that sometimes there will be conflicts between spending time in his career and spending time with his family.

For example, he had to turn down an invitation to present a talk at an international conference this spring because his wife, Christiana, is expecting a baby soon. He recalls a mentor in medical school advising him that “Medicine will take as much of your life as you will give it.” So Jon is conscious of finding an arrangement that works best for his career and family.

Fortunately, he and Christiana, who works from home as a proposal manager for a design-build construction firm based in San Diego, make a great team. And they have the help of a nanny who comes during the workweek from 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., which is essential to Christiana’s getting her work done. When the nanny is off-duty, Jon and Christiana share tasks—Christiana takes care of bath time, Jon covers cooking and nap times, and they take turns handling other chores. They expect to be able to manage with two children, but when asked if they had thought about having a third, Jon laughed and said it was not likely because another child would require changing tactics entirely from man-on-man coverage to zone defense.

Another important question for many young professionals is when to start a family. Jon reflected that although it was great to be married for seven years kid-free, perhaps they could have started sooner. But there’s a trade-off: Having kids earlier could mean the parents have more energy, but having kids later often means the parents are more mature and financially secure. This financial security is particularly important, Jon says, when you assume what kids want to do will be expensive—such as attending college when they grow up. Having a family makes Jon feel that his work is even more important, because now he is providing for his kids to pursue their dreams.

There can be other financial strains, too. NIH employees are allowed to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave—or can substitute vacation time, sick leave, or donated leave—for the birth or adoption of a child. Jon was able to use annual leave when his son was born, but he’s concerned about others who might only be able to use unpaid leave. He wonders if NIH could have a fund to help people who can’t live on a reduced income.

Jon plans to be flexible with his future postdocs. “Having an infant is harder than being on call for 30-hour shifts,” he said. “You don’t get the post-call afternoons off.”

Even though managing a family and a career can seem overwhelming at times, the trade-offs have been worth it for Jon and Christiana. Jon describes being with his family as “refreshing” and caring for patients as a “gut-check” to put his own family’s good health in perspective.

“Kids force you to be involved. They have to come first,” Jon said. “And having your kid say, ‘I love you’ makes you feel important in a pure way.”

Family Friendly

Cynthia E. Dunbar, M.D., Senior Investigator, Molecular Hematopoiesis Section, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Spouse: Charles Cerf, retired; previously worked as a stock analyst on Wall Street; then as a teacher (taught computer applications) in Washington, D.C., public schools

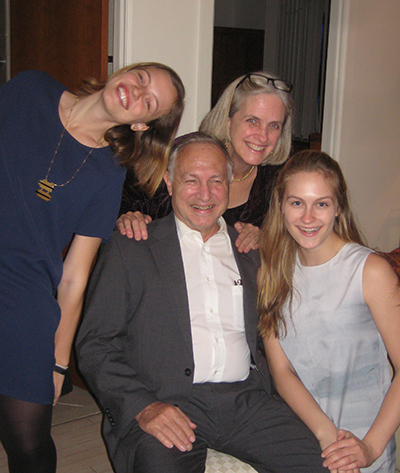

Children: 2 daughters Alexa (25), Anna (23); 2 step-children, Amin (49), Nabil (45); 4 step-grandchildren

Cynthia’s family (from left): Alexa, Charlie, Cynthia, and Anna

Success in science involves lots of hard work but also some luck. Cynthia Dunbar admits that she’s had her fair share of both in becoming a senior investigator and the mother of two young children. She came to NIH as a postdoc in 1987 (in the lab of Arthur Nienhuis), was promoted to a tenure-track investigator in 1991, had two daughters, and achieved tenure (early) as a senior investigator in 1996. All of that requires hard work…and quite a few elements working out just right at home and at work.

Success in science involves lots of hard work but also some luck. Cynthia Dunbar admits that she’s had her fair share of both in becoming a senior investigator and the mother of two young children. She came to NIH as a postdoc in 1987 (in the lab of Arthur Nienhuis), was promoted to a tenure-track investigator in 1991, had two daughters, and achieved tenure (early) as a senior investigator in 1996. All of that requires hard work…and quite a few elements working out just right at home and at work.

She was lucky that by the time she and her husband Charlie—the father of two grown children from a previous marriage—had their children, he was no longer in a high-stress Wall Street job and was a teacher and musician in Washington, D.C., public schools. And he was working from home by the time their daughters were in school.

“I had it easy,” said Cindy. “I had a husband who had already done his career thing.” As a teacher, Charlie worked fewer and more predictable hours than she did, and after his retirement from the school system, he was able to provide the in-home presence after school. They also had a nanny before the children began school. Having such a supportive husband and relatively easy and healthy children, Cindy could give as much of herself to work as was needed. She was still involved with family activities and, when the girls were older, even managed their soccer teams and leagues.

Another timely break happened when Nienhuis moved to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (Memphis, Tennessee) and Cindy’s lab absorbed some of his excellent trainees. Having independent and motivated senior technicians and postdocs was invaluable for Cindy’s success. Although she didn’t spend an exhaustive amount of time physically present in the lab, these laboratory members kept the research moving forward effectively even when she was out on maternity leave. However, it perhaps helped that she was able to function on four hours of sleep a night and was extremely efficient. This hard work paid off: Not only did she get promoted to senior investigator, but she also became the first female editor-in-chief for the journal Blood.

Cindy, who was interviewed for an article on parenting in the November–December 1996 issue of the NIH Catalyst [https://nihsearch.cit.nih.gov/catalyst/back/96.11/balance.html], noted that several things have improved at NIH since her children were young: There are more child-care spots on campus (although still not enough!); more work can be done remotely; and more trainees are willing to raise children in apartments instead of insisting on the need for a single-family home, which might require a long commute.

On the downside, housing is more expensive near campus; commutes are longer for families that find less-expensive housing elsewhere; salaries are not rising at the same pace as child-care costs; and there is an increased expectation for how much work needs to be done to publish a paper.

In the 1990s, “the pace of research was much slower, and expectations for a published paper were lower,” she said. “It was more hours in the lab [then], but now things can be done at home, even though it’s more work.” Overall Cindy wants to remind fellows that hours and work location are much more flexible in a translational investigator position at NIH or elsewhere in academia. She found working in academia more family-friendly than working in industry or as a full-time clinician.

Cindy wishes she could help more women become independent scientists running their own labs. “I’m a little depressed that I’ve trained a lot of principal investigators who are men, but not a single woman,” she said. She thinks this situation speaks to something she sees in the next generation of female scientists–a lack of confidence and lack of professional support. Awards and fellowships with strict timelines, such as the Lasker Clinical Research Scholars Program, hurt women who have children during training. This choice (to start a family) can temporarily reduce productivity. Policies that support women who want both career and family would be beneficial.

As for the lack of confidence, most trainees don’t see science as family friendly, to which Cynthia replies, “What could be more family friendly than being your own boss?”

Her family today: Alexia works in computer technology in San Francisco; Anna will be designing gap-year programs in Boston after college graduation this spring; Amin works in finance; and Nabil works in forestry.

Find Your Own Path

Linda Wyatt, Ph.D. Staff Scientist in Laboratory of Viral Diseases, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Richard Wyatt, M.D. Deputy Director, Office of Intramural Research, Office of the Director

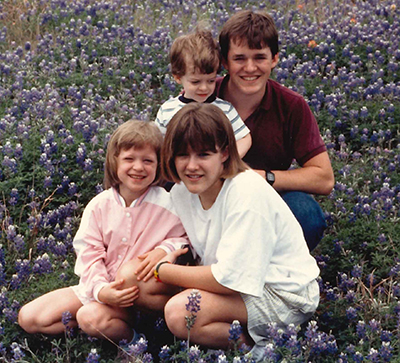

Children: Two sons and two daughters: William (48), Katherine (44), Grace (38), Gregory (34); six grandchildren

Wyatt children in 1986: (front row, left to right) Grace (6) and Katherine (12); (back row) Greg (2) and Will (16)

Both Linda and Richard Wyatt have dedicated decades of service to the NIH, with no signs of slowing down. They find their work inspiring, challenging, and enjoyable. Richard’s career followed a fairly standard and successful trajectory. After earning a medical degree and doing a residency in pediatrics, he was commissioned in the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps in 1971 as a research associate in the NIAID Laboratory of Infectious Diseases. He was promoted to senior investigator in 1976 and has been serving in the Office of Intramural Research since 1984. Richard was able to focus more time on his work, thanks to Linda, who took 10 years off between two postdocs to support and nurture the children.

“We operated on one income,” said Richard. “We intentionally recognized the constraints.” He realizes, however, that the cost of living and other factors make being a one-income family much more difficult for today’s generation of parents.

Linda, who already had two children of her own when she came to NIH as a postdoc in NIAID in 1974, was able to snag rare spots in NIH’s nascent child-care program. When she and Richard married in 1978, they jointly agreed that Linda would stay home and be there to meet their children’s needs. They did not envision this state of affairs to be permanent solution, and it wasn’t.

“I had the best of both worlds,” said Linda. “I got to be a stay-at-home mom and then came back to work” as a senior research fellow. This second postdoc helped her get back to the lab when her youngest was in kindergarten. She credits a senior woman scientist who gave her the opportunity to re-enter science “despite the gap of 10 years.”

“Now child-care issues are major for entry-level scientists,” said Richard, who’s a member of NIH’s Child Care Board. He expressed concern that trainees are not eligible for child-care subsidies (NIH employees are) and that at least 50 percent of child-care spots are required to be filled by children of federal employees (neither trainees nor contractors are considered employees). These factors contribute to significant problems for fellows debating the “choice” between family and science. As a staff scientist in a research lab with postdocs, Linda sees this struggle first hand. She herself never desired to become a principal investigator because she did not see it as being compatible with committing time to the family. Many women trainees “want to be mothers,” which means they want to work but not in what is perceived as the stressful, demanding position of principal investigator, she said.

Once Linda returned to work, managing four children and supporting two careers called for extra help. The Wyatts never wanted their children to come home to an empty house, and they didn’t want the older children to be fully responsible for the younger ones. With no family nearby, their solution was live-in help—an au pair for five years and a nursing student who helped with child care for seven years. Even with the extra help, family time together remained a priority for the Wyatts, and they regularly had breakfast and supper together.

“The NIH has been a wonderful place to work, great for couples,” said Richard. In addition, Linda has noticed that the NIH is becoming more flexible about hours logged in the lab, and younger trainees also appear to have a healthier perspective on work-life balance. The Wyatts recognize that the way they balanced children and careers worked for them, but every scientist and parent needs to find their own path to success at work and at home.

What are the children doing now? William is working in computer science; Katherine has an M.B.A. but stays at home for now with four children; Grace is at graduate school for counseling and has two children; Gregory has a master’s in security studies and works overseas.

Kids Add So Much Fun to Life

Judith R. Walters, Ph.D., Section Chief, Neurophysiological Pharmacology Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

Spouse: None

Children: 3 sons (Jamie, 40 years old); (Gregory, 37 years old); Douglas (33 years old); one granddaughter

This photo taken in 1988 shows (from left) Gregory (age 8), Douglas (age 4), Jamie (age 11), and Judie Walters.

A lot has changed since Judith Walters, or “Judie” to her friends at the NIH, received her Ph.D. in pharmacology from the Yale University School of Medicine in 1972 for studying the role of dopamine neurons in the basal ganglia. Judie, only the sixth woman to earn a Ph.D. from the school’s Department of Pharmacology, has witnessed many advancements in neurology research since then. She has also seen the expansion of her own family and changes in the parenting challenges for the researchers conducting science.

There was no maternity leave when Judie came to NIH in 1975. After she had her first child by cesarean section in 1977, she came back to work just two weeks later. Judie recalls how hard it was to leave her baby for the first time yet feeling guilty for wanting to stay at home longer. She felt indebted to the male-dominated culture that had given her the opportunity to do research. But at a scientific meeting in Sweden a year later, she had a flash of insight when she learned that Sweden guaranteed a one-year maternity leave. This fact made Judie feel that her desire to be home with her newborn was not unreasonable.

Planning for her second pregnancy, Judie requested a month’s maternity leave and her PI’s permission to work part-time for a couple months after her return. However, she soon realized she would work as much as usual during the “part-time” weeks, so she soon rescinded her request and returned to work full-time. By the time she had her third child, she felt comfortable going back to work after a month.

Judie felt lucky to have the phenomenal help of a local woman named Caroline, who took care of the children during the week, did light housework, and helped with dinner. When the boys turned three, they began going to morning nursery school as well. Judie would even drive home to have lunch with her boys sometimes.

Kids add so much fun to life, Judie said. “Adding the complexity of kids is a big plus.” A parent’s love for their children is “an uncomplicated type of love” that makes all the lifestyle adjustments worth it, “even in the teen years, which can be a bit crazy.”

Today, Judie is particularly sensitive to the challenges faced by young working parents. She noted that there are better—albeit typically way more expensive—child-care options than when she was raising her sons. As a member of one of the NIH Child Care Board’s subcommittees and senior advisor on Women’s Issues for the Deputy Director for Intramural Research, Judie works to support—and improve—child-care and other parent-friendly programs for fellows and other NIHers.

It’s hard for Judie to watch postdocs struggle with being working parents. She tells them to “hang in there” because it will be gratifying to be at an older stage in life and have both wonderful, grown children and fascinating science in their lives. When her last son went off to college, Judie admits that she was excited to get to be a “total workaholic.” There are different stages in life, and Judie is proof that even the hardest one (raising children) is doable.

Her children are grown and independent now. Jamie is an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas). He and his wife have a five-year-old daughter, Ayelle, whom grandmother Judie adores. Ayelle shows interest in many areas as evidenced by her terrarium, microscope, and ballerina tutu. Gregory is a journalist in Washington, D.C., and Douglas is a musician and an aspiring music producer in Los Angeles, California. Greg, also a musician, recently wrote and performed a tender, lighthearted song about his mother’s work. It encourages Judie to think that her kids are proud of her. She feels very lucky to have them—as well as interesting science—in her life.

Meet the Authors and Their Families

Michelle Bond (staff scientist, NIDDK): Riker (age 4) and his mom on the occasion of his pre-school graduation (2017).

Anne Davidson (postbac, NICHD): Anne’s mom (Robin) took this photo (left to right): Beth, with their huskie Nanook, Anne, her twin brother Chris, and their dad (Darrell) holding their Samoyed Nishka (Christmas 2017).

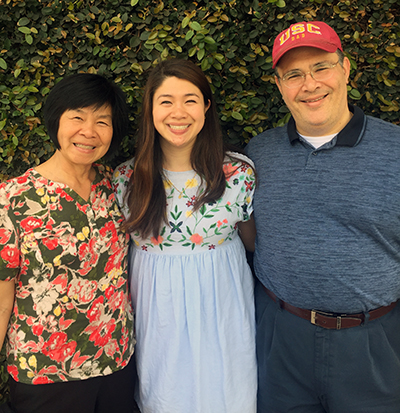

Clarissa James (postbac, NIMH): Clarissa (middle) and her mom (Fern) and dad (Bill).

Laura Carter (Editor-in-Chief, NIH Catalyst) and her family in the 1980s (from left): Laura, Sarah (now 37), Geoff, and Emily (now 35).

Emily Petrus (Research Fellow, NIDDK) and her husband Ionel in winter 2016 with their sons Gabriel (now 6) and Daniel (now 2).

This page was last updated on Thursday, April 7, 2022