NIH in History

Taming Dreaded Diseases in the 1800s

Joseph Kinyoun, the Hygienic Laboratory, and the Origins of the NIH

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

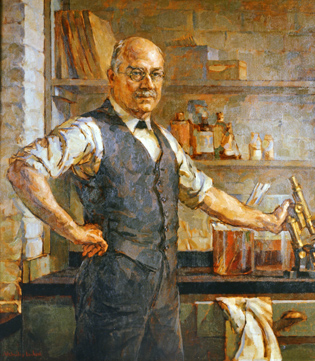

Portrait of Joseph J. Kinyoun (1860–1919) by Walmsley Lenhard (1891–1966). The oil painting is based on a photograph from 1918, making Kinyoun look much older than he was during his years as director of the Hygienic Laboratory, the predecessor of the National Institutes of Health.

In Building One on the NIH campus, next to the main floor elevators, hangs a portrait of a middle-aged man with rolled-up sleeves, one hand on his hip, the other on a shiny brass microscope. A plaque identifies the subject as “Joseph J. Kinyoun, Director of the Hygienic Laboratory, 1887-1899.”

The National Institutes of Health traces its origins back to the Hygienic Laboratory (HL), the first federal laboratory of medical bacteriology. At first a modest facility of applied science, it later expanded its scope of research, budget, staff, and facilities. It was renamed the National Institute of Health in 1930, 11 years after Kinyoun’s death, and the National Institutes of Health in 1948.

Bacteriology was a hot topic in the 1880s. German physician Robert Koch’s description of the life cycle of the anthrax bacillus in 1876 (and his subsequent discovery of the tuberculosis bacillus in 1882 and the cholera vibrio in 1883) excited physicians and biologists and spurred many of them to search for disease-causing germs. The first generation of microbiologists in the United States was not one of basic scientists, but of physicians, veterinarians, and chemists working for the federal government or state and municipal health departments.

Joseph Kinyoun was one of those physicians. The son of a surgeon in the Confederate Army, he received his M.D. degree from Bellevue Hospital Medical College in New York in 1882 and trained at the Carnegie Laboratory (also in New York) in 1885. In 1886 he entered the Marine Hospital Service (MHS), a seemingly inauspicious career move that would catapult him into becoming an important figure in the history of microbiology and public health.

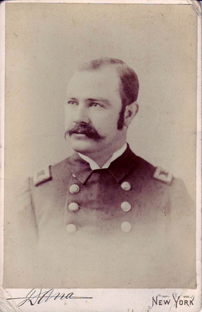

KINYOUN FAMILY ARCHIVES

Assistant Surgeon Joseph James Kinyoun of the Marine Hospital Service. Studio portrait from 1887, the year he opened the Hygienic Laboratory, predecessor of the NIH.

Surgeon General John B. Hamilton selected Kinyoun to set up the HL because he was one of just a handful of Americans trained in bacteriological techniques at the time and the only one in the MHS (predecessor of the Public Health Service). The laboratory was first located at the Stapleton Hospital (Staten Island, N.Y.), one of several facilities in the Port of New York that catered to newly arrived immigrants and seamen, treating the sick among them and placing carriers of infectious diseases in isolation.

But, already in 1888, the laboratory’s mission was much broader than serving quarantine activities with bacteriological analysis: It also dealt with matters “pertaining to the successful administration of national quarantine and the dealing with public sanitation and hygiene.”

NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Kinyoun’s Zeiss microscope, which he used to study cholera, was very advanced and expensive in the 1880s.

Kinyoun modeled the HL on Koch’s laboratory in Berlin (but on a smaller scale), including “Zeiss’s latest improved microscope objectives and microphotographic apparatus.” Kinyoun soon used this microscope to study cholera, one of the most dreaded diseases in the 19th century. The opportunity to conduct this research presented itself in September 1887, when an Italian steamship arrived in New York. Eight immigrants on board were sick with cholera; eight others had died during the voyage. The ship went straight to quarantine and the sick passengers were hospitalized. More cases developed and more deaths occurred during the following weeks.

William H. Smith, the quarantine health officer, described the disease as “very virulent and rapid in its fatality in a majority of the cases; in several instances patients that were well at inspection in the afternoon were nearly or quite pulseless within twelve hours.” The whole ship, every passenger, all the cargo and luggage, and every piece of clothing were disinfected twice. The ship was held for two weeks and repainted before being released.

Together with his colleague Samuel Treat Armstrong, Kinyoun collected samples of “excreta” from isolated cholera patients and cultivated them on agar plates. Three days later, they found “characteristic colonies of the comma bacilli…conforming in every particular to the description given by Koch.” This was the first time cholera was identified by means of a microbial investigation in the Americas. “As the symptoms, in the cases examined, were by no means always well defined, the examinations were confirmatory evidence of the value of bacteria cultivation as a means of positive diagnosis,” they wrote in the New York Medical Journal in 1887.

Kinyoun then went on to test the waters in New York Harbor to determine whether cholera could survive and spread through the water. The answer was yes. Therefore, the “dejecta” of cholera patients needed to be handled safely (presumably by sanitizing latrines and burying their contents instead of simply emptying them into the water). Although this study was of minor scientific importance, the medical community and the general public received it as chilling, sensational news. Medical journals and newspapers kept referring to the study throughout the spring of 1888. Even in faraway Iowa, the Cedar Rapids Evening Gazette commented, “It is extremely unpleasant to know that Dr. J. J. Kinyoun, of the Marine Hospital Service, has proved that the Asiatic cholera spirilla thrives and reproduces ad libitum in the water of New York Bay.”

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

From the first location of the Hygienic Laboratory in the Marine Hospital Service facility at Stapleton Hospital (Staten Island, N.Y.). Kinyoun’s microscope can be seen in the center on the bench by the window.

With these studies Kinyoun made his name and laboratory known. He began appearing frequently in the national arenas of medicine and science: He often represented the MHS at meetings of the American Medical Association and the American Public Health Association and published articles in their journals. Newspapers reported on his work and his travels to European laboratories and international congresses. Health departments around the country called on him to assist with investigations and to teach their physicians how to conduct bacteriological tests or “biological examinations,” as they were called at the time.

When Walter Wyman became surgeon general in 1891, he moved the HL to MHS headquarters in Washington, D.C., across the street from the United States Capitol. The HL was now a few blocks from the Army Medical Museum and Library and close to other government agencies such as the Department of the Treasury and the Department of Agriculture with its Bureau of Chemistry.

The move—from a peripheral hospital to a place next door to the federal government—made the HL more visible to policymakers. Kinyoun began to take on broader issues and assumed a higher profile. His work became less clinical and more scientific, administrative, and political. When a second cholera outbreak afflicted the Port of New York in 1892, Wyman and Kinyoun were successful in getting new legislation passed that increased the power of the MHS over local and state authorities.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Marine Hospital Service headquarters in Washington, D.C., at 222 New Jersey Avenue SE. The whole top floor belonged to the Hygienic Laboratory.

Kinyoun was one of a growing group of physicians and scientists in the United States and abroad who enthusiastically adopted the new science of microbiology and harnessed it to serve the interests of public health. During his 12 years at the HL, he published papers on bacteriology and public health; inspected disease-ridden ships and disinfected them; studied the efficiency of various disinfecting agents and methods; analyzed the microbial environment of railway cars, the water of the Potomac, and the air of the House of Representatives; compiled an exhibit on the Marine Hospital Service for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago; produced and advocated the use of diphtheria antitoxin; and drafted public health legislation. This was what public health was all about at the end of the 19th century: a combination of microbiology, epidemiology, and sanitary science and engineering.

To read more about Kinyoun’s life, visit http://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/whoweare/history/josephjkinyoun/indispensableman/Pages/default.aspx.

This page was last updated on Friday, April 29, 2022