Research Briefs

NICHD, CC: RARE CANCERS MAY MASQUERADE AS ADHD IN CHILDREN

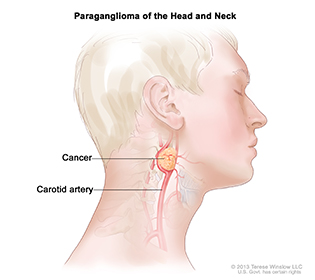

FOR NCI © 2013 TERESE WINSLOW LLC, U.S. GOVERNMENT HAS CERTAIN RIGHTS

Paraganglioma, a rare tumor that often forms near the carotid artery, is one of two types of tumors that may cause the same symptoms as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children. It may also form along nerve pathways in the head and neck and in other parts of the body.

Rare tumors called pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas may cause the same symptoms as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children, leading to inappropriate treatment that could worsen their symptoms and potentially endanger their health. The tumors secrete catecholamines—substances that stimulate the central nervous system. NICHD and CC researchers evaluated 43 children with these tumors from January 2006 to May 2014. Nine of the children (21 percent) had been diagnosed with ADHD before their tumors were discovered. Four of the nine had been treated with stimulant drugs typically prescribed for ADHD (amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, or methylphenidate), which caused some to develop headaches, excessive sweating, and hypertension. After their tumors were removed, three of the nine children no longer experienced ADHD symptoms. The study authors suggest that high blood pressure accompanying a diagnosis of ADHD could be a warning sign that the child may have something more than a hyperactivity disorder and that pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas should be on the list of potential causes. (NIH authors: M. Batsis, A. Stratakis, T. Prodanov, G.Z. Papadakis, K. Adams, M. Lodish, and K. Pacak, Horm Metab Res DOI:10.1055/s-0042-106725, http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-106725).

NCI: INCREASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY ASSOCIATED WITH LOWER RISK OF 13 TYPES OF CANCER

A new study by NCI researchers reports that more leisure-time physical activity (such as walking, running, swimming, and other moderate-intensity to vigorous activities) is associated with a lower incidence of 13 different types of cancer. Past research showed that physical activity reduces the risk of heart disease and death from any cause in addition to lowering the odds of developing colon, breast, and endometrial cancers. However, much less is known about its influence on other cancers.

To examine this issue, the investigators evaluated data on self-reported physical activity levels and the prevalence of 26 different types of cancer from 12 datasets that were part of the Physical Activity Collaboration of NCI’s Cohort Consortium. Altogether, the data included information on 1.44 million American and European adults, ages 19 to 98. The analysis confirmed that leisure-time physical activity is associated with a lower risk of colon, breast, and endometrial cancers. It also determined that leisure-time physical activity was associated with a lower risk of 10 additional cancers, with the greatest risk reductions for esophageal adenocarcinoma, liver cancer, cancer of the gastric cardia, kidney cancer, and myeloid leukemia. Myeloma and cancers of the head and neck, rectum, and bladder also showed risk reductions that were significant, but not as strong. Risk was reduced for lung cancer, but only for current and former smokers; the reasons for this are still being studied.

The authors propose that physical activity may reduce cancer risk by altering concentrations of certain hormones such as estrogen and insulin; by reducing inflammation and oxidative stress; and by boosting immune function. Future studies by the group will examine how specific types and amounts of physical activity affect cancer risk. (NIH authors: S.C. Moore, J.N. Sampson, C.M. Kitahara, S.K. Keadle, H. Arem, A. Berrington de Gonzalez, P. Hartge, D.P. Check, N.D. Freedman, M.S. Linet, C. Schairer, and C.E. Matthews, JAMA Intern Med 176:816–825, 2016, http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=2521826)

NIAID, CC: INVESTIGATIONAL MALARIA VACCINE PROTECTS HEALTHY ADULTS

An experimental malaria vaccine protected a small number of healthy, malaria-naïve adults in the United States from infection for more than one year after immunization, according to results from a phase 1 trial. The vaccine, known as the PfSPZ vaccine, was developed and produced by Sanaria Inc. of Rockville, Maryland, with support from several Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) awards from NIAID. NIAID researchers and collaborators at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore conducted the clinical evaluation of the vaccine, which involved immunizing and exposing willing, healthy adults to the malaria-causing parasite Plasmodium falciparum in a controlled setting.

The phase 1 trial took place at the NIH Clinical Center and at the University of Maryland Medical Center (Baltimore) and enrolled 101 healthy adults aged 18 to 45 years who had never had malaria. Of these volunteers, 59 received the PfSPZ vaccine; 32 participants served as control subjects and were not vaccinated. Vaccine recipients were divided into several groups to assess the roles of the route of administration, dose, and number of immunizations in conferring short- and long-term protection against malaria.

Collectively, the data showed that the PfSPZ vaccine provided malaria protection for more than one year in 55 percent of people without prior malaria infection. In those individuals, the vaccine appeared to confer sterile protection, meaning the individuals would be protected against disease and could not transmit malaria to others. The vaccinations were also well-tolerated by participants, and there were no serious adverse events attributed to vaccination.

Additional results showed that antibodies may play a role in malaria protection early after the final immunization, but inducing T cells in the liver is likely necessary for durable protection. Long-term, reliable protection is important for people who are vaccinated but not exposed to malaria for months, such as travelers and military personnel. Durable protection is also important for mass vaccination campaigns aimed at interrupting transmission in malaria-endemic regions, according to the authors. (NIAID authors: A.S. Ishizuka, A. DeZure, F.H. Mendoza, M.E. Enama, I.J. Gordon, L.-J. Chang, U.N. Sarwar, K.L. Zephir, L.A. Holman, S.H. Plummer, C.S. Hendel, M.C. Nason, L. Novik, P.J.M. Costner, J.G. Saunders, B. Flynn, W.R. Whalen, J.P. Todd, J. Noor, S. Rao, K. Sierra-Davidson, G.M. Lynn, B.S. Graham, M. Roederer, J.E. Ledgerwood, R.A. Seder; CC authors: H. DeCederfelt, M.A. Kemp, and G.A. Fahle, Nature Med 22:614–623, 2016, http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/nm.4110.html).

FOGARTY: ANALYSIS OF 1976 EBOLA OUTBREAK HOLDS LESSONS RELEVANT TODAY

With the recent Ebola epidemic in West Africa reviving interest in the first outbreak of the deadly hemorrhagic fever 40 years ago, scientists led by Joel Breman of NIH’s Fogarty International Center have released a report highlighting lessons learned from the smaller, more quickly contained 1976 outbreak. (NIH author: J.G. Breman, J Infect Dis DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiw207, http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2016/06/28/infdis.jiw207.abstract)

NIDDK: SOME “BIGGEST LOSERS” GAIN BACK THE WEIGHT

It’s hard enough to lose weight, but when the body counters your efforts by slowing your resting metabolic rate (RMR) and burning fewer calories, it’s hard to keep the weight off. An NIH follow-up study of 14 contestants in the TV show The Biggest Loser found that six years later they’d regained an average of 90 pounds after having lost an average of 130 pounds. In addition, their RMR was, on average, as low as it had been at the end of the competition. Despite the weight regain, the show’s participants “overall were quite successful at long-term weight loss compared with other lifestyle interventions,” the researchers reported. “Therefore, long-term weight loss requires vigilant combat against persistent metabolic adaptation that acts to proportionally counter ongoing efforts to reduce body weight.” (NIH authors: E. Fothergill, J. Guo, L. Howard, R. Brychta1, K.Y. Chen, M.C. Skarulis, M. Walter, P.J. Walter, and K.D. Hall, Obesity DOI:10.1002/oby.21538, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/oby.21538/abstract)

NIAMS, NIAID: RAPID-RESPONSE IMMUNE CELLS ARE FULLY PREPARED BEFORE INVASION STRIKES

CREDIT: HAN-YU SHIH AND JOHN O’SHEA, NIAMS; ALAN HOOFRING, NIH DIVISION OF MEDICAL ARTS

NIMAS researchers have discovered that innate lymphoid cells, early responders of the immune system, are primed at the DNA level for rapid action.

Through the use of powerful genomic techniques, NIAMS and NIAID researchers have found that during the development of immune cells called innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), these cells gradually become better prepared for rapid response to infection. ILCs appear to play a critical role in defending the body’s barrier regions, such as the skin, lungs, and gut, through which microbes must pass to make their way into the body. Working in mice, the researchers analyzed regions of the genome that control the cytokine genes produced by both ILCs and T cells. The study reflected earlier findings that ILC and T-cell subclasses produce similar sets of cytokines, but those earlier studies also revealed differences in how the two cell types control the activities of these key immune response genes. While the regulatory landscapes of ILCs are primed for a quick defense upon infection, those of T cells are minimally prepared when the pathogen invades. Only after infection are modifications in the landscape made that enable T cells to launch their attack. (NIH authors: H.-Y. Shih, G. Sciumè, Y. Mikami, L. Guo, H.-W. Sun, S.R. Brooks, J.F. Urban Jr., F.P. Davis, Y. Kanno, and J.J. O’Shea, Cell 165:1120–1133, 2016, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.029)

NIAAA: NONMEDICAL OPIOID USE DOUBLED IN 10 YEARS

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids more than doubled among adults in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013, according to a study conducted by NIAAA scientists. In 2012–2013, nearly 10 million Americans, or 4.1 percent of the adult population, used opioids—a class of drugs that includes oxycodone (trade names include OxyContin) and hydrocodone (trade names include Vicodin)—without a prescription or took more than was prescribed in the previous year. This is up from 1.8 percent of the adult population in 2001–2002. Scientists analyzed data from NIAAA’s National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III (NESARC-III), an ongoing study that examines alcohol- and drug-use disorders among the U.S. population as well as associated mental-health conditions.

Overall, the study found that nonmedical prescription opioid use among U.S. adults increased by 161 percent from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013, while prescription-opioid-use disorder increased by 125 percent. The authors suggest that this increase may be due in part to increase in opioid prescribing and dosage, lessened perception of risk because of its legality, and lack of understanding of the addictive potential.

The researchers found that nonmedical prescription opioid use and prescription-opioid-use disorder are linked to other drug-use disorders and to a variety of mental-health disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder and certain personality disorders. Persistent depression and major depressive disorder are linked to nonmedical prescription opioid use, whereas bipolar I disorder is linked to prescription-opioid-use disorder. (NIH authors: T.D. Saha, R.B. Goldstein, S.P. Chou, H. Zhang, J. Jung, R.P. Pickering, W.J. Ruan, S.M. Smith, B. Huang, and B.F. Grant, J Clin Psychiatry 77:772–780, 2016, http://www.psychiatrist.com/JCP/article/Pages/2016/v77n06/v77n0614.aspx)

NCI, NCATS: VISUALIZING PROTEINS INVOLVED IN CANCER-CELL METABOLISM

Using cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM), NCI scientists have broken through a technological barrier in visualizing proteins with an approach that may aid drug discovery and development. They captured images of glutamate dehydrogenase, an enzyme found in cells, at a resolution of 1.8 nanometers (1.8 angstroms), a level of detail at which the structure of the central parts of the enzyme could be visualized in atomic detail. The scientists and their colleagues also showed that the shapes of cancer target proteins considered too small to be within the reach of current cryo-EM capabilities can now be determined at high resolution. (NIH authors: A. Merk, A. Bartesaghi, S. Banerjee, V. Falconieri, P. Rao, M. Davis, R. Pragani, M.B. Boxer, L.A. Earl, J.L.S. Milne, and S.Subramaniam, Cell 165:1698–1707, 2016, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27238019)

NICHD, CC: SOME WOMEN WITH PCOS MAY HAVE ADRENAL DISORDER

A subgroup of women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a leading cause of infertility, may produce excess adrenal hormones, according to an early study by researchers at NICHD, the NIH Clinical Center, and other institutions. The researchers noted that earlier studies had found that in some women with PCOS, androgens are produced by the adrenal glands rather than by the ovaries. In the current study, the researchers found that 15 of the 38 women with PCOS who volunteered for the study produced more adrenal hormones than normal and also had adrenal glands that were smaller than normal.

The researchers theorize that the women’s adrenal glands may resemble those seen in a condition called micronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia—in which tiny lumps or nodules appear on the adrenal glands and begin producing adrenal hormones. Because the nodules produce hormones, the adrenals produce fewer hormones and shrink.

Additional studies with a larger number of patients will be needed to examine the adrenal glands of women with PCOS to confirm the study results and to determine whether the women have micronodular adrenocortical hyperplasia or some other condition affecting the adrenal glands. (NIH authors: NICHD: E. Gourgari, M. Lodish, M. Keil, C. Lyssikatos, M. Nesterova, M. Sierra, P. Xekouki, C.A. Stratakis; CC: N. Sinaii, E. Turkbey, J Clin Endocrinol Metab DOI:10.1210/jc.2015-4019, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27336356)

FOGARTY: IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE APPROACHES TO REDUCE MOTHER-TO-CHILD HIV TRANSMISSION

An emerging field, known as implementation science, may help reduce the nearly 150,000 instances of mother-to-child transmissions of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that occur annually around the world, mostly in developing countries. A team of scientists and program managers, led by Fogarty’s Center for Global Health Studies, has been studying a variety of implementation science approaches to prevent mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) and has published the results in a 16-article open-access supplement to the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (http://journals.lww.com/jaids/toc/2016/08011).

In implementation science, scientists study how to integrate research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine care and services. The researchers reported on the effectiveness of a variety of interventions including collaborating with churches to invite pregnant women to “baby showers,” which included HIV testing and gifts; administering pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among pregnant and breastfeeding women in sub-Saharan Africa; and deploying a point-of-care test for infant diagnosis of HIV using a portable, battery-operated device that may result in more timely initiation of drug therapy. “Continuing to find innovative ways to foster collaboration of implementation science researchers with decision makers and program implementers will be critical to speed the translation of effective PMTCT interventions in the local context and health system programs,” the authors concluded. (NIH authors: R.I. Glass and D.L. Birx, J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 72 (Supplement 2): S101, 2016; whole supplement spans pages S101–S206, http://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2016/08011/AdvancingPMTCTImplementationThroughScientific.1.aspx)

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 13, 2022