NLM Workshop: Images and Texts in Medical History

An Introduction to Methods, Tools, and Data from the Digital Humanities

Seventy-five participants and observers gathered at the Natcher Conference Center (Building 45) in April 2016 to explore innovative methods and data sources useful for analyzing large quantities of images and texts in the field of medical history.

Made possible by an NEH grant to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (Virginia Tech) as well as generous support of the Wellcome Trust, “Images and Texts in Medical History” included a presentation about the Medical Heritage Library (MHL), a digital curation collaborative among some of the world’s leading medical libraries; a keynote address by Jeremy Greene (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore); hands-on sessions with Benjamin Schmidt (Northeastern University, Boston) and Miriam Posner (University of California, Los Angeles); and a showcase of innovative digital-historical projects.

Invited experts offered guidance on digitizing printed and visual historical materials as well as perspectives on what materials are appropriate to archive. Some simply may not be appropriate due to their physical condition or to privacy issues that need to be navigated thoughtfully in order to provide access for historical research. Workshop participants exchanged ideas on a variety of related topics, including current best practices in using digital tools to study digitized historical materials in order to ask and answer new questions about disease diagnosis and treatment as it has changed over time.

Medical Heritage Library (http://www.medicalheritage.org/)

The MHL has a growing digital footprint that includes works spanning six centuries, all of which are available freely through the Internet Archive (https://archive.org/index.php). NLM is one of the founding partners of the MHL, and it remains one of its primary contributors as a means of making its own vast collections freely available to the world.

“There are between four and seven million medical records out there,” said Aimee Mederios (University of California at San Francisco, San Francisco). “If printed and stacked, they would be over seven times the height of Mt. Everest.” Mederios explained further that the MHL represents a dedicated community of scholars, librarians, and technical specialists who are working together to address and overcome the challenges of preserving these important collections and making them accessible in thoughtful ways for historical and contemporary research.

“There are a variety of ways now to mine digitized historical texts,” said Melissa Graf (Yale Medical Library, New Haven, Connecticut). “Mining images is more challenging because, far too often, digitized images are ‘locked’ in digital files.” For instance, to locate images of patients with black bands over their eyes (a technique once used in patient photos to hide identity), you can’t just search for “black bands over eyes.” New digital tools allow us to overcome challenges such as this and be able to examine large quantities of digitized historical images in new ways, as opposed to simply studying one image at a time. That traditional practice remains important, but opportunities now abound to combine that practice with reading a large number of images with new digital tools.

Phoebe Evans Letocha (Johns Hopkins, Baltimore) discussed ways to improve access to sensitive patient-related materials that are often in hidden collections in hospitals and medical departments and in danger of being destroyed. Her recommendations included archivists and researchers working more closely together to advocate for changes in patient privacy laws that balance the need for privacy with the need for scholarly access. Polina Ilieva (University of California at San Francisco) also addressed the difficulties of producing meaningful collections of medical records.

Keynote: Jeremy Green

Today’s new digital technologies “all have parallels in similar encounters with analog media half a century earlier,” said Greene in his keynote address “The Analog Patient: Imagining Medicine at a Distance in the Television Era.” In describing how two-way, closed-circuit television became a high-tech tool for clinical practice, medical research, and physician education beginning in the 1960s, he highlighted two early successes of telemedicine—one at the University of Nebraska Medicine Center (Omaha) and the other at Logan International Airport in Boston.

At the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Cecil Wittson and Reba Bernschoter pioneered the use of two-way closed-circuit television to enable face-to-face communication between the Nebraska Psychiatric Institute in Omaha and the Norfolk State Mental Hospital (Norfolk, Nebraska), located 112 miles away. The system was used for teleconferences, patient care in which a psychiatrist could monitor patients and read electroencephalographs, and family visits via telelink.

The telemedicine clinic at Boston’s Logan airport in the 1960s enabled health-care providers to share information on patients with providers at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Green also told how a 1960 plane crash—caused by a flock of starlings flying into the plane’s engine as it was taking off from Logan—was the impetus for the establishment of a telemedicine clinic. Only 10 of the 72 on board survived. Although the airport was only three miles from Massachusetts General Hospital, the overcrowded highway system kept emergency rescue and medical personnel from reaching the crash site quickly. So three years later, an emergency medical station was set up at Logan’s gate 23. At first the station’s director, Kenneth Bird, relied on the telephone to communicate with the hospital’s round-the-clock expert medical care. He quickly realized, however, that telephone consultations weren’t enough—doctors needed to be able to see the patients, too. In 1968, he founded the first telemedicine system, which used interactive television to link the Logan station with doctors at the hospital who supplied remote diagnosis, interpreted medical images that were transmitted via the link, and prescribed treatments.

To see a videocast of Greene’s presentation, go to http://videocast.nih.gov/launch.asp?19613, and to learn more read a recent article in the June 3, 2016, issue of the NIH Record (https://nihrecord.nih.gov/newsletters/2016/06_03_2016/index.htm).

Hands-on Sessions

In the hands-on sessions, workshop participants learned about digital tools for analyzing text and images.

“Text Analysis Tools and Methods”: Benjamin Schmidt (Northeastern University, Boston). Using examples from medical journals, Schmidt guided workshop participants through the use of tools that identified term clustering across articles in ways that could facilitate large-scale text mining by historians exploring journals available from the MHL in a variety of formats. These techniques allow historians to see large-scale patterns, such as changing terminology, which would be difficult to identify at scale using conventional approaches.

“Digital Tools for Analyzing Images”: Miriam Posner (University of California at Los Angeles). Posner demonstrated the use of image-detection software that can analyze photographs of medical subjects published in books, pamphlets, and journals. These tools are especially valuable because the meaningful content of photographs often is not specified in captions that appear on text versions of publications. Tagging images—an approach ubiquitous in today’s social media—thus has applications for historical scholarship, as illustrated in this workshop.

New Projects at the Intersection of Medical History and Digital Humanities

Seventeen workshop participants presented three-minute summaries of their digital projects. As diverse as the digital collections they represented, these projects included:

- Advertisements depicting the use of antibacterial hexachlorophene: First used in Dial soap in 1948 and other products such as Stripe toothpaste, the chemical was found to be a neurotoxin and banned from use in consumer products in 1972. A tool called Datawrapper was used to summarize the data. (Martha Gardner, Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Boston)

- Documenting and analyzing diverse stories of rayon, the first “manmade” material, across geographical boundaries, national borders, and corporate fence lines. Some of the stories involved carbon-disulfide poisoning in the 1920s, industrial waste, and toxic-shock syndrome linked to rayon in tampons. (Jongmin Lee, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia)

- “Exploring medieval miracle stories” addressed how contemporaries determined whether an individual was suffering from a humoral imbalance (such as melancholy, mania, or frenzy) or from presumed demonic possession. (Leigh Ann Craig, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia)

- “Misuse of digitized medieval medical images” focuses on the plague to raise awareness of the unintended consequences of mislabeling and misrepresenting infectious diseases in the past and to demonstrate how the “viral” spread of misinformation creates a distorted view of the past. (Lori Jones, University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada)

- “Medieval Object Lessons: The Harvard Digital Library of the Middle Ages (MOL)” offers over 100 objects from medieval Europe and the Middle East in interactive three-dimensional formats, accompanied by full descriptions, links to related online materials, bibliographies, and suggested classroom and curricular uses. (Allyssa Metzger, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts)

- “Managing Mary: Dutch Public Discourse on Morphine” uses digitized newspapers to analyze the role of references to the United States in Dutch drug debates in the first half of the 20th century. (Lisanne Walma, Utrecht University, Uretcht, the Netherlands)

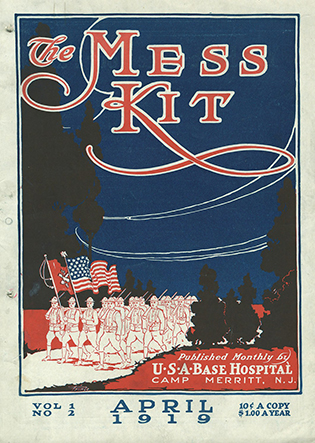

- “Sense and Sensibility: The Power of Print in Post-war Magazines” includes about 1,500 scanned pages from the pages of military magazines that showcase daily life in American hospitals, cities, and towns shortly after World War I. (Jeffrey Reznick, NLM)

NLM

This newsletter is part of NLM’s collection of military magazines.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, April 13, 2022