An Exit Interview with NIH Library Director Suzanne Grefsheim

Photo: Michael Spencer

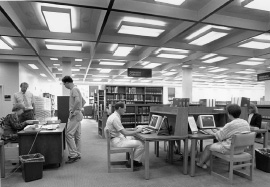

The NIH Library has undergone a transformation over the past 20 years in both its spirit and its physical appearance. Gone are most of the stacks, not to mention the dark rugs. Brilliant light now fills its first floor, which is best described as an information commons where users can relax and even, dare we say, eat and talk.

Suzanne Grefsheim, who came to direct the library in 1992 from a similar position at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, nurtured this transformation. As she prepared to retire on May 31 to turn her attention to her gardening hobby, Suzanne spoke to The NIH Catalyst about what she helped plant and grow at the NIH. The following is an edited transcript of that interview.

You oversaw some rather dramatic changes in library services in the 1990s. Perhaps this wasn’t entirely different from one of your favorite hobbies, gardening.

Yes. When we were trying to create the learning organization in the late ’90s, the staff would ask, “Why do we need to change so much?” And I said, “Well, it’s like a garden. You see ways that it could be so much better. So you pull it up and reconfigure it.” We did that with the library physical space as well as with its mental space—compartments that library staff put themselves into.

Photo: NIH Library

The NIH Library’s reading room before Suzanne Grefsheim arrived in 1992 (above), was not as inviting and sun-filled as it is today (below).

Photo: NIH Library

Was this place a weedy mess in 1992?

Not really. Just different. When I came to NIH, the library was committed to service in an exemplary way, but it was not looking at how things were changing. The staff felt that its role was to do the work. My vision was to create a self-sufficient user population. There was a bit of resistance among the librarians to taking on a teaching role at first. There was resistance among the users, too, because they were so used to having someone do things—like searching—for them. But that resistance was quickly overcome.

How easy was this in 1992? Did the state of technology even allow this?

We were the first at NIH to offer the Internet. We were the first to provide unlimited access to Medline (now PubMed) to NIH, too. When I was at the University of Michigan health sciences library, we were the first to negotiate an agreement with a Medline provider so we could have unlimited access to Medline for a flat rate. For the NIH Library, I made a similar deal with the National Library of Medicine. I knew from experience that once Medline was freely accessible, users would love it.

How long did it take for things to change?

I spent the first five years changing the mindset about the kinds of services we could provide. The next five years we tried to change the way the staff itself worked. We had to be more nimble, willing to take on new responsibilities and roles, and not be stuck in the traditional “wait till people come to you” mindset. If we were pushing out all our resources to users’ desktops, we had to figure out a way to reach them. This whole period of learning and growing and staff development led to and culminated in the informationist program, which is now blossoming.

Ah, another garden reference. Informationists are embedded librarians who house themselves physically among the research team they serve. Is this concept growing elsewhere, too?

Not in the same way we are doing it. There was a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association describing the informationist program. We’re mentioned as one of three model programs. Ours is more clinical- and basic-research-oriented because of the nature of this institution. (JAMA 305:1906–1907, 2011)

Some people never step inside the NIH Library. Does that bother you?

No! Actually, that was the goal—that they wouldn’t have to come here. The purpose of the library isn’t to be a physical place. The library is the suite of services and resources that we make available, in whatever format, in whatever location they’re needed. Librarians are what make that happen. But there is a role for a physical facility, and we have spent the last five or six years trying to repurpose ours into what the new library can be. It’s now sort of an intellectual meeting place. It also provides space that’s needed for fellows who don’t have offices.

Photo: NIH Library

Many of the library’s training programs are held in attractive glassed-in rooms like this one (above). Outside, library patrons can read, relax, and even compute on the terrace (below).

Photo: Bradley Ottersnon

What was it like when you came?

It was brown, very brown.

Like some gardens?

Well, not a particularly nice garden. The carpeting was brown—with high shelves all over blocking out sunlight. Very book oriented, very journal oriented. And wood, the same color as the carpet. Everything was brown. It really was an uninviting place. The most heavily used part of it was the photocopy center—long, long lines of people waiting for the nine photocopiers that we had and being told they could only stay at the photocopier for five minutes. The library was originally designed, in a way, to limit access. But we wanted to break down the barriers and let people get as much as they wanted whenever they wanted it with no limits. The electronic resources allowed us to do that.

What services are you particularly proud of?

We were the first on campus to offer the Internet in the early ’90s. We were the first to have wireless access. We were the first to do many things that brought the NIH into the information age. Outside of NIH the informationist program is viewed as a groundbreaking area. The bioinformatics program has been hugely successful and will likely grow. We’ve conducted research studies to identify emerging needs and what the scientists wanted from us. That’s what led to the formation of our writing center. Our services have always exemplified what the library is. It’s the content, not the container.

Peering into the future, what dangers do research libraries face?

You have to be thinking 10 years ahead. A lot of libraries aren’t. If they think that the library is the books and the journals and the place, and that people will come to them, they aren’t going to survive. Libraries that are built as showcases tend to be underutilized. They become too invested in doing the same things in a new space instead of doing new things in a minimum space. I was once asked whether I wanted a new building. I said “Absolutely not.” We are right where we need to be, among the people who use us the most.

How about advice for the next NIH Library director?

You have to understand the community you are serving, know its culture, and understand how researchers think and approach information. You cannot assume that you have the answers.

This page was last updated on Monday, May 2, 2022