The Health Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

BY CAROLINE STETLER, NIEHS

CREDIT: NIEHS, HEATHER PATISAUL

NCCIH and NIEHS, with support from the NIH Office of Disease Prevention and Office of Dietary Supplements, hosted the “Complementary and Integrative Interventions to Mitigate the Effects of Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals” workshop

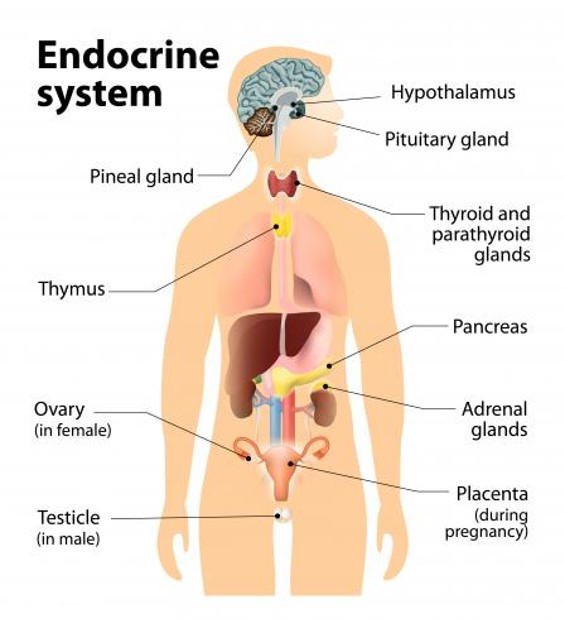

NIH scientists recently gathered with grantees, clinicians, and community members to discuss emerging research focused on interventions—simple, accessible, and safe steps people can take—to mitigate exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). These chemicals interfere with hormones produced by the endocrine system, which controls metabolism, heart rate, growth, reproduction, and other biological processes.

During the two-day workshop held June 10-11 in Bethesda, Maryland, panelists called for more solutions-focused research, clinical trials to assess benefits of holistic interventions such as diet and physical activity, and health care provider education.

“We’ve discovered many different chemicals that are used widely—such as [perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances], pesticides like [dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane], and plastic-related chemicals like phthalates and bisphenol A [BPA]—can all impact health and the health of future generations through endocrine-disrupting effects,” said NIEHS Director Rick Woychik during the workshop jointly organized by NCCIH and NIEHS.

CREDIT: NCCIH

Sekai Chideya

“Every day there seems to be a new headline about EDCs and forever chemicals having an effect on our health and well-being, and possible links between EDCs and obesity, cancers, ADHD [attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder], immune dysfunction, or fertility problems,” said Sekai Chideya, program director at NCCIH. “We must find ways to clear EDCs from our bodies, block their effects, or build defenses and resiliency because trying to avoid these chemicals is unlikely to prevent the health effects EDCs may cause.”

The goal, according to Chideya, is to empower the public to do something about EDC exposure and risk reduction, as well as inspire researchers and the public to collaborate with NIH, so we all stay healthy and thrive in the face of EDCs.

CREDIT: STEVE MCCAW, NIEHS

Heather Patisaul described the endocrine system’s role in reproduction, growth, metabolism, stress, calcium balance, blood pressure, and blood glucose.

What are EDCs?

“EDCs are a little bit different than overt poisons in that they perturb our endocrine system,” said Heather Patisaul, scientific director of the NIEHS Division of Translational Toxicology. “And there isn’t an organ or cell in your body that the endocrine system doesn’t touch.”

According to Patisaul, the term “endocrine disruption” was coined in 1991, marking the beginning of an era when scientists began further understanding how chemicals can affect our bodies and health. The timing of EDC exposure, particularly during critical windows such as pregnancy and even at low doses, can significantly perturb the endocrine system and other organ systems. However, regulation of these chemicals has lagged.

“Consumer demand, not a regulatory action, got BPA out of baby bottles and flame retardants out of furniture,” Patisaul explained. “There’s a lot of power when groups come together and ask for change.”

Diet, probiotics, supplements, and sweating out chemicals

NCCIH Director Helene Langevin applauded efforts to figure out how to mitigate the effects of these toxic chemicals, especially through lifestyle changes, such as nutrition education, physical activity, and stress management, that have wide-ranging benefits.

Key takeaways from research presented during the workshop include the following.

- Eating a diet high in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, as well as low in sugar, along with physical activity and sufficient sleep, is known to improve overall health. Emerging research shows the benefits may also extend to a person’s ability to reduce the effects of EDCs.

- Consuming higher-quality diets and decreasing exposures to nonpersistent EDCs improved pregnancy and maternal metabolic health outcomes, according to studies conducted by Rita Strakovsky, Michigan State University (East Lansing).

- Karen Peterson, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) and longtime NIEHS grantee, shared research showing lower intake of ultraprocessed foods may reduce EDC exposure levels and cardiometabolic risk among women in midlife.

- Eating probiotic yogurt or fermented foods may help boost gut microbes that act as a barrier of protection against heavy metals that are EDCs, such as arsenic, mercury, and lead, according to studies conducted by Jordan Bisanz, Pennsylvania State University at University Park.

- Regularly induced sweating can reduce the levels of EDCs, said Detlef Birkholz, an analytical consultant. His team found concentrations of BPA that were consistently higher in a person’s sweat than urine, suggesting sweat may be a better indicator of toxicant levels and more accurately capture the true burden of some EDCs.

- Emerging research indicates supplements such as fish oil, folate, and probiotics to support the gut microbiome, and stress management using mindfulness techniques, could provide benefits.

- If possible, avoid and reduce exposure to consumer products containing EDCs (see sidebar).

CREDIT: HORMIS BEDOLLA

Hormis Bedolla of the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas (a national organization of women farmworkers) explained the human costs of EDCs that she and family members experienced.

The human cost of EDCs

Community members representing firefighters, farmworkers, and veterans, who have been disproportionately exposed to EDCs in the workplace, as well as those affected by polluted drinking water, shared their perspectives during the workshop.

Hormis Bedolla of the Alianza Nacional de Campesinas shared photos of injuries she sustained after applying pesticides at an apple orchard. She also shared photos of her children. All were born premature and underweight, including one child who underwent heart surgery and another who was in the neonatal intensive care unit for two months, which she attributes to her decades-long work using pesticides that contain EDCs.

“As farmworkers, we are the ones feeding the nation, but we are not being seen or recognized,” said Amy Tamayo, Bedolla’s colleague who acted as her interpreter. “We are continuously facing the horrible consequences of pesticide exposures.”

CREDIT: STEVE MCCAW, NIEHS

Thad Schug

Calls for health care provider education

“Our institute has been studying endocrine disruptors for a long time,” said Thad Schug, program director at NIEHS. “We know the many ways the chemicals can harm our bodies, we know we should reduce exposure, and we know many of the bad chemicals, but how to proceed from here is the big question.”

Sheela Sathyanarayana, University of Washington (Seattle), called on workshop participants to write an open letter to the Association of American Medical Colleges advocating for incorporating environmental components into the curriculum for all medical students. The goal would be to educate health care practitioners on EDC exposure.

“Hearing from the impacted communities was very powerful and underscored the critical importance of interfacing with and talking to them even more,” Patisaul said. “It is their needs and priorities, after all, that we are tasked with addressing. NIH needs to do a better job of learning from them, responding to their needs, and prioritizing their health.” Patisaul said she is hopeful the engaging and stimulating meeting leads to new partnerships and initiatives.

“We have reason to hope that so much of the outstanding research discussed in the last two days is pointing us in the right direction,” added Langevin to conclude the conference.

The complete list of workshop speakers and their bios can be found here, and all presentations from both days are available here in both English and in Spanish.

Caroline Stetler is editor-in-chief of the Environmental Factor, produced monthly by the NIEHS Office of Communications and Public Liaison.

Steps You Can Take

Carmen Messerlian, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (Boston) and NIEHS grantee, shared a few steps people can take to reduce exposure to EDCs.

- Mop floors to reduce dust and chemicals picked up in the dust.

- Reduce the number of personal-care products you put on your body.

- Reduce the number of times you eat takeout per week.

- Invest in a water filtration system, whether low-cost or over-the-counter water filters, or a reverse osmosis system.

Moving the needle down to create a new habit is the key, says Messerlian.

This page was last updated on Tuesday, December 3, 2024