Viruses on the Brain

Avindra Nath investigates the mysterious ways viruses affect the nervous system.

Dr. Avindra “Avi” Nath

The COVID-19 pandemic was not Avindra “Avi” Nath’s first face-off with an enigmatic, rapidly spreading virus.

A newly minted neurology resident in 1983, Dr. Nath unexpectedly found himself treating a growing group of patients — mostly well-educated, homosexual men —with severely weakened immune systems. As he and his colleagues fought to keep these patients alive, Dr. Nath watched with his neurologist’s eye as they experienced subtle cognitive changes that doctors with other specialties might have missed.

“That was the beginning of the AIDS pandemic,” Dr. Nath recalls. “It was a really transformative experience in my life because my patients were dying in droves, and they were socially isolated — their families didn’t want anything to do with them and society didn’t want anything to do with them — but I was taking care of them and watching them develop all these neurological complications.”

Scientists soon discovered that AIDS is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), prompting Dr. Nath to begin a journey towards becoming one of the world’s foremost experts on how viruses affect the brain. Now the Clinical Director at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the head of its Section of Infections of the Nervous System, he occupies a unique niche that requires expertise in two seemingly unrelated fields.

“If you’re trained as a neuroscientist or neurologist, you understand the functions of the brain, but if you’re trained as a virologist, you study viruses, and there’s no way you would get exposed to the intricacies of the brain,” Dr. Nath explains. “I trained in both, so I was able to marry the two together.”

Dr. Nath at a hospital in Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, with a pediatrician who was treating Nodding syndrome patients.

That rare combination of skills has made Dr. Nath one of the U.S.’s go-to guys when outbreaks of infectious disease occur. Over the past two decades, he has repeatedly visited Liberia to help combat Ebola; he has been to Brazil several times to study the Zika virus, which caused a pandemic in 2015 and 2016; and he was invited to Uganda by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to learn about Nodding syndrome, a mysterious disease causing seizures in children. He has also continued to study HIV, and most recently he has lent a hand to the ongoing war against COVID-19. The common thread among all of these illnesses, he says, are their under-recognized effects on the brain.

“What happens with most pandemics and viral infections is that people get focused on the effects on the organ system that causes the acute symptoms,” Dr. Nath says. “If patients forget things or are not behaving normally, their doctors just blame some other explanation for it rather than thinking that the disease itself might be the cause.”

Dr. Nath dressed in personal protective equipment to visit an Ebola patient at the NIH Clinical Center.

However, thanks to the work of scientists like Dr. Nath, it is becoming increasingly accepted that all of those diseases affect the brain. This change in attitude can perhaps be seen most clearly in the study of HIV. Even though antiretroviral therapy has dramatically lengthened the lifespans of people with HIV by preventing the virus from multiplying inside their bodies, many patients still experience a spectrum of neurological symptoms collectively referred to as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND). These symptoms, which may occur in up to 30-50 percent of people living with HIV, include problems with memory and attention, mood disorders, and loss of coordination. A small number of patients even develop severe dementia.

Dr. Nath’s team has discovered that a protein produced by HIV, called Tat, is present in the brains of HIV-positive patients even when antiretrovial therapy has reduced the amount of virus in their blood to undetectable levels. He believes that HIV hides from antiretroviral drugs inside brain cells, remaining unscathed by the therapy while continuing to release Tat, which causes brain inflammation and kills neurons.

“Even if antiretroviral therapies cross the blood-brain barrier, they cannot prevent HIV proteins from being made inside infected brain cells,” Dr. Nath explains. “We think that, if you want to control HIV completely, you have to control the Tat protein.”

Myoughwa Lee, Ph.D., a research scientist in Dr. Nath’s lab, dissects a mouse brain with the help of a microscope.

Dr. Nath’s lab is now developing ways to do just that. The group’s efforts focus on creating single-stranded, DNA-like molecules called antisense oligonucleotides that can be used to dampen the activity of a specific gene — in this case, the gene that HIV uses to make Tat. The lab is also testing drugs called ‘checkpoint inhibitors,’ which have recently begun to see use in cancer immunotherapy, in the hopes that the drugs can help spur patients’ immune systems to destroy HIV-infected cells.

At the same time, Dr. Nath is attempting to uncover the secrets of SARS-CoV-2, the virus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. When it became apparent that many COVID patients continue experiencing symptoms like fatigue and difficulty concentrating long after contracting the virus — a syndrome now known as ‘long-COVID’ — it reminded him of his experiences working with patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). Dr. Nath’s research has suggested that ME/CFS might be a residual effect of viral infections, and these observations prompted him, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, to urge his peers not to discount the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 could wreak havoc on the brain.

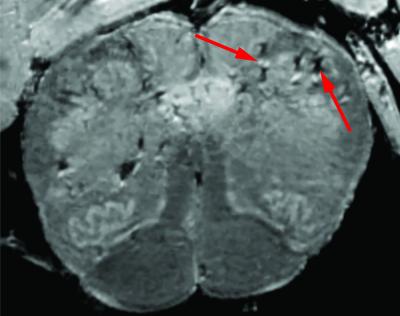

Since then, Dr. Nath’s research has only bolstered that warning. His team’s studies have found significant damage to blood vessels and neurons in the brains of deceased COVID-19 patients, hinting that long-COVID may be the result of a virus-induced assault on the brain with consequences that linger after the body has successfully fought off the virus.

This brain scan of a deceased patient who had COVID-19 shows signs (red arrows) of damaged blood vessels.

“The same concepts repeatedly come full-circle,” he says.

Discoveries like those being made in Dr. Nath’s lab promise to dramatically alter how the long-term effects of viral infections are treated. As patients with ME/CFS have long known, when doctors cannot objectively measure symptoms, they can be quick to dismiss those symptoms entirely. Yet this narrow-minded approach can lead to the neglect of large groups of patients, from those with HIV-induced neurological problems to people living with ME/CFS and, most recently, individuals suffering from long-COVID. After a nearly 40-year career exploring consequences of viruses that many of his peers have long ignored, Dr. Nath has come to appreciate the unique struggles of such patients and the importance of not repeating the mistakes of the past.

“You have to be very careful,” he says. “People who had COVID-19, this serious respiratory illness, are also complaining of neurological symptoms, and these symptoms may actually be persistent. We have to pay attention to this and not ignore it.”

Avinda Nath, M.D., leads the Section of Infections of the Nervous System at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), where he also serves as Clinical Director.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023