Taking the Long View

Mark Schiffman uses molecular epidemiology to predict and prevent cervical cancer.

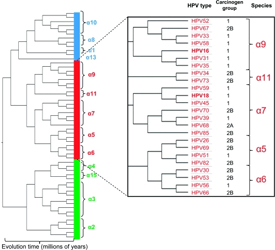

Evolution of HPV types predicts carcinogenicity, as demonstrated in collaborative work among Dr. Schiffman, Dr. Robert Burk of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, and colleagues

Preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organized efforts of society—this is one definition of public health, a science that has enticed many researchers who are willing and able to face its demands.

“The biggest challenge working in public health research is that it requires taking the long view,” says Mark Schiffman, M.D., M.P.H. “And, when it comes to continuity, there just aren’t many institutions that can support a single research project over the span of multiple decades.”

Dr. Schiffman charts the natural history of HPV

At the NIH, much of Schiffman’s 30-year career in the IRP has involved analyzing data from long-term cohort studies, lasting more than 15 years in some cases, aimed at understanding the risks of developing cervical cancer. His team’s research has related human papillomavirus (HPV) status to health outcomes for more than 100,000 women around the world, which, in combination with molecular epidemiological data, contributed to the finding that persistent HPV infection causes essentially all cervical cancers.

“Epidemiology is both an etiologic and translational science,” Schiffman says. “The more we’ve understood the role of HPV in cervical carcinogenesis, the more our work has shifted towards applying what we know. So we’ve been working in Africa and in Latin America to try to figure out whether there could be a cheaper, robust, easily translatable set of products that can help prevent cervical cancer where it’s most important, which is in low resource places.”

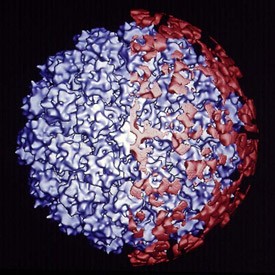

The HPV vaccine molecule contains virus-like particles (blue) that are noninfectious and stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies (red) that can prevent HPV infections

Both high-risk and low-risk types of HPV can cause the growth of abnormal cells, but only high-risk HPV leads to cancer. At least a dozen high-risk types have been identified; including HPV types 16 and 18—two forms that together cause about 70 percent of all cervical cancer cases. Realizing that HPV is the foundation of cervical cancer, researchers developed a very sensitive test for HPV. Further advances by Douglas Lowy, M.D., and John Schiller, Ph.D., senior research scientists at the National Cancer Institute, led to an effective vaccine that was commercialized in 2006. A national vaccination effort is now in place for all 11- or 12-year-old girls and boys in the U.S.

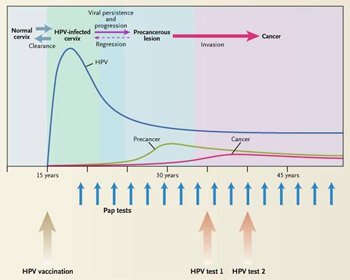

The natural history of human papillomavirus (HPV) progresses over multiple decades

For women 21 to 64 years old, in addition to vaccination, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) currently recommends a pelvic exam with Pap smear (the standard cytological screening test used to detect pre-cancerous and cancerous cells in the cervical region) every two years. However, in March 2012, as a result of ongoing public health research—including work performed at the NIH—landmark, multi-institutional recommendations were published that challenge existing guidelines and the current paradigm of biennial cytological testing, proposing instead a single five-year exam, including the highly sensitive HPV test, for women ages 30 to 65 years.

“It makes a lot of sense from a public health point of view to reduce the frequency of the current exam, a cytological test, and to add the more sensitive HPV test, because it’s only when certain types of HPV virus cannot be cleared that they become a risk factor for cervical cancer,” explains Schiffman, co-author on the new guidelines.

Schiffman co-authored the latest “Screening for Cervical Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation” guidelines

Schiffman’s pragmatic approach to public health stems from a desire to address social justice issues around the world. Long-term dedication to epidemiological research on cervical cancer control—from understanding the molecular and genetic factors of HPV that make it a carcinogen, to guidelines for screening frequency and vaccination schedules, and the implementation of each in a global context—illustrates his ambition to constantly advance medical knowledge and provide improved public health initiatives to those in need. Recently, Schiffman’s public health colleagues at the IRP found that vaccination against HPV does not accelerate clearance of existing virus and that two doses of the HPV vaccine, possibly even one dose, might be as protective as the currently recommended three doses.

The Team: From left to right: Hormuzd Katki, Arpita Ghosh, Sholom Wacholder, Lisa Mirabello, Mark Schiffman, Julia Gage, Megan Clarke

“The global implications of these findings are enormous in terms of public health,” Schiffman says. “Regions with limited resources may now be able to offer the vaccination to more women, potentially saving many lives.”

Having always known that he wanted to be a public servant, after 30 years at the NIH, Schiffman remains a champion for the scientific truth, ensuring that health screening and prevention guidelines continue improving as new evidence becomes available.

Mark Schiffman, M.D., M.P.H., is a Senior Investigator in the Clinical Genetics Branch of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics at the National Cancer Institute.

Further reading:

- Multi-institutional cervical cancer screening guidelines

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) cervical cancer screening guidelines

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 24, 2023